Archives of Thursday Comics Hangover

Thursday Comics Hangover: The mysterious Goddess

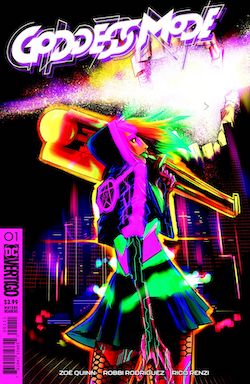

Usually we expect the first issue of a comic to clearly lay out the premise of a series and introduce readers to the world of the story. The first issue of Goddess Mode, the new Vertigo comic from writer Zoë Quinn and artist Robbi Rodriguez, is the exception that proves the rule.

I've read this issue of Goddess Mode three times already and I honestly don't know where the book is going from here. Is it a Matrix-like story of a woman fighting for freedom in a virtual world? Is it a Brazil-like story of a cog in a bureaucratic machine who struggles against the social forces that are holding her back? Is it a Gibsonesque story of lawless frontier technology? I'm still not sure; it could be all three.

Goddess Mode begins in a virtual realm (it's described as "Everywhere. But also nowhere. Kind of.") where a warrior woman (who describes herself as "a barely functioning bundle of neuroses who can't master putting on a fitted sheet") fights a starfish-looking monster. But most of the book is the story of Cassandra Price, a "junior artificial intelligence support assistant" who gets swept up into a swirl of great expectations, both within her all-powerful corporation and without.

While it's not yet clear if Goddess Mode will be a liberation story or a Dick-ian exploration of self in a futuristic setting or an investigation of the emotional impact of video games (or, again, all three,) it is obvious that the book is good comics.

Quinn relays a lot of exposition with very little awkwardness, and Rodriguez's art is a fascinating blend of the futuristic (his tech looks lived in and unobtainable) and the organic (his skill at body language is remarkable.) The color palette for the book, by Rico Renzi, is a refreshing blend of turquoises and pinks and purples — less of a sterile iPhone future and more of a neon smear.

A caption box at the end of this issue of Goddess Mode promises a few answers to some of the most nagging narrative questions in the next issue — mainly, what's with the team of fierce warriors who show up to recruit Price at the end of the issue? With this first chapter, Quinn and team have earned the right to keep readers guessing for a while longer.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Illegal, aliens

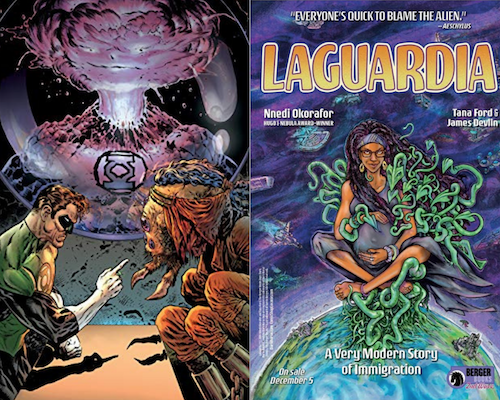

Grant Morrison is two issues into a run on Green Lantern, and it's a glorious mix of Silver Age DC Comics and Heavy Metal magazine. The book is aggressively weird — one Green Lantern is a virus, another is a big, muscular body with an exploding volcano for a head — but it is at its heart a police story. There's an interrogation scene and a deathbed confession and all the tropes you'd find in a Law & Order episode, only with magic rings and bird-people.

Artist Liam Sharp is doing the work of his life on this book: in the past, his art has seemed better-suited for horror, but the weird sci-fi of Green Lantern is something else again. There's enough detail on every page to take out a reader's eye, and very few artists in general seem as uniquely skilled as Sharp at getting Morrison's enormous concepts down smoothly on paper.

Still, I have to admit to some uneasiness with the book. Green Lantern here is presented as a bit of a prick. (He calls himself a "bastard" at one point.) And his respect for the rights of criminals is, shall we say, less than robust. Morrison is hardly a rabid conservative, so the weird authoritarianism in Green Lantern is likely to be a setup for some kind of a revelation later on. It's surely the most beautiful book that DC is publishing right now, and there are high-concept ideas on every single page of the book, but this isn't the time to elevate a hardline law and order agenda in a comic book.

This week also saw the first issue of a new comic series written by sci-fi writer Nnedi Okorafor. Like Green Lantern, Laguardia features bizarre aliens and high-concept sci-fi throughout. But unlike Green Lantern, Laguardia is interested in the personal struggle against law enforcement.

Beautifully illustrated by Tana Ford, Laguardia is the story of a very pregnant Nigerian woman named Future who flies in to the Laguardia International and Interplanetary Airport ("the only airport with interplanetary travel services in North America.") There's a complex and thoughtless customs process to navigate, and the airport is teeming with aliens making their way to and fro: small, green germlike creatures, a man with a carrot for a head. They're coming to America.

Laguardia is a futuristic story about one of the oldest human concepts: borders, and what they do to us. Future has a plan to upturn America's anti-alien culture (it involves an alien named Letme Live) and she's not afraid to break a few laws to do it. Between Future and the Green Lantern, I know where my loyalties lie.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The heart of a poet

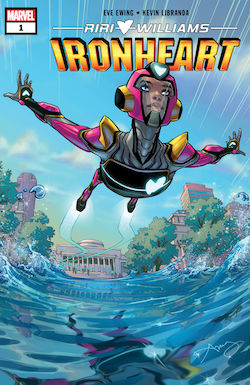

In her poem "Origin Story," Eve L Ewing writes "love is like a comic book. it’s fragile/and the best we can do is protect it." Ewing is a restless genius: depending on how you came to her work, you might know her first as a poet or a visual artist or an activist or an academic.

But if you've follow Ewing on Twitter for any amount of time, you likely know that she's an unabashed nerd. And her poem about comic books, it turns out, was a premonition of another title for her yard-long resume: Riri Williams: Ironheart, Ewing's first project as a comic writer, was published by Marvel Comics yesterday.

If you don't know anything about the character, Ewing catches you up in the first few pages of Ironheart. Riri Williams is a brilliant Chicago teen who, after tragedy strikes, reverse-engineers a suit of Iron Man's armor and decides to become a superhero.

Riri is a classic Marvel hero: impossibly smart, good-hearted, socially awkward, and a little bit of a self-defeatist. Ironheart #1 has pretty much everything you need in a superhero's first issue: character development, the introduction of a cast of characters, a villain with an ambitious plan, a big fight, and a soap-operatic last page twist.

The art by Kevin Libranda and Luciano Vecchio plays the range well — not every figure looks like a musclebound brute, the facial expressions are all clear and believable, and the action is imaginative. The coloring, by Matt Milla, is especially great. (You can see the light of Riri's phone on the underside of her nose when she gets a video call from a friend, and other nifty lighting tricks are handled subtly but intelligently.)

But for me, the real thrill of the issue is coming across Ewing's poetic flourishes in the dialogue. Riri takes a moment in a battle royale to appreciate her own accidental alliteration. The bad guy explains his plan, as is tradition, and then adds with a flourish, "You know, sometimes you just have to take a moment to revel in your own gifts." Indeed.

And Riri's personal motto — "those who move with courage make the path for those who live in fear" — isn't quite as catchy as Spider-Man's "with great power comes great responsibility," but it provides a complicated thesis for Ewing and company to explore over the rest of the series.

Ewing displays a natural talent for writing comics, and Riri is an interesting character who has enough provocative weaknesses to keep the story interesting for years to come. Ironheart is quite possibly the best first issue of a Marvel character since G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona's Ms. Marvel. This comic is anything but fragile.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A dress unknown

I'm still making my way through the mammoth stack of Short Run books I bought earlier this month. It's not a chore at all — I love reading minicomics — but it's rare when a book stands up and demands my attention.

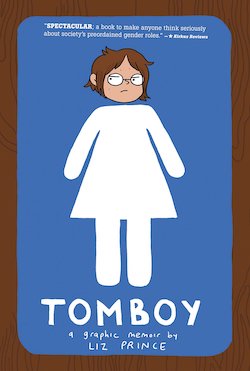

One of the attention-grabbiest comics in this year's Short Run haul for me is Liz Prince's memoir Tomboy. This is a memoir about Prince's lifelong struggle with gender conformity, focusing mainly on her school years.

"I DON'T LIKE ANY DRESS," Prince yells as a toddler in the beginning of Tomboy. "I HATE THEM!" Those who believe that gender is a hard and fast rule would do well to read about Prince's instinctual revulsion against any item of clothing that could be considered girly. This is not a choice; it's how she was born.

And Tomboy isn't all about clothes. It's about how Prince learned to accept herself, and how she was not always accepted by her peers. Prince is a charming and accessible narrator, and her art is clean and accessible — kind of a perfect cross between John Porcellino and Julia Wertz.

As Prince ages over the course of the book, her challenges become more and more complex. The gender norms of high school begin to crush her spirit. She doubts her own resolve. But Prince's understanding of herself also deepens, and that understanding gives her the strength to be true to her own calling.

Tomboy is funny and sweet and deeply reflective. It's the kind of book that will sing directly into someone's ear. It will inspire a shock of recognition in some tomboys, and it will help more than a few readers come to the realization that not everyone feels comfortable dressing like a generic gendered figure sign on a bathroom door. It's such a personal document that everyone has something to learn from it.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Shedding some light on the subject

Maybe I'm jaded, but I don't see much in comics that strikes me as especially new anymore. It's not so much that it's all been done, it's just that very few people are still trying to push the medium forward in exciting ways. Who is experimenting with the medium and form of comics? Who is trying to break comics out of normalcy?

The first name that comes to mind when conjuring a list of comics experimenters is Seattle cartoonist Eroyn Franklin. I've previously called Franklin one of the greatest mad scientists working in comics today, and I just encountered one of her older works that strikes me as one of her boldest and most inventive works.

At Short Run last weekend, while visiting Franklin's booth, I asked about a book called A New Home. She demurred slightly, saying it was an old book and that she was working on a newer version. I bought the book anyway, and holy cow am I glad I did.

On the face of it, A New Home might sound like a gimmick. Here's the deal: the book is made up of silhouettes and splashes of color. It doesn't have panels; it's laid out like more of a picture book. So you look at a page, which has large, clear images and a few words. One page, for example, has the outline of a monster with its head reared back. The monster is white; the background is black. The words "And down, down, down she went" are in the upper right corner. It's a striking, minimalist image.

Franklin colored the reverse side of this page a deep, bloody red, and she drew a figure tumbling into a pit. So when you hold the page up to a strong light, a new dimension reveals itself: the inside of the monster turns red, and we can see it swallowing a woman. Every page of the book has a hidden secret that reveals itself when you hold the page up to light.

Comics are a dance between words and pictures. But with A New Home, Franklin adds a new partner to the dance: words and pictures interact, and then they interact again with the pictures on the other side of the page, creating a lively third dimension that lives in a realm that's perpendicular to the comics page.

A New Home is a simple story about a woman who goes exploring and faces grave danger. But the way each page reveals its secrets creates a new tension to the fable Franklin tells. Sometimes the secrets are gory. Sometimes they're pleasant. Sometimes they change the way the reader feels about the story.

Franklin is always moving and trying to discover new ways to tell stories through comics. But I hope she'll take a while to pause and reflect on the storytelling technique she employed in A New Home. The depth and excitement she brings to the page here with a simple but effective gimmick is too good to cast aside as a single experiment. There are new dimensions here for Franklin to explore, and a new light to view comics through.

Thursday Comics Hangover: All-singing, all-dancing

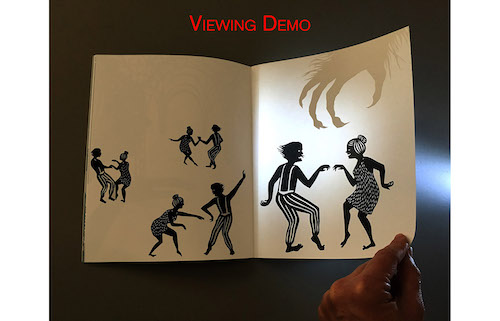

A panel from Rina Ayuyang's Blame This On the Boogie.

It's a clear sign of the Short Run Comix & Arts Festival's rising fame that Montreal comics publisher Drawn and Quarterly chose the festival for the world premiere of cartoonist Rina Ayuyang's new memoir Blame This On the Boogie. Ayuyang will appear at Short Run on Saturday and she'll be in conversation with Seattle cartoonist Megan Kelso at the Central Library on Sunday at 1 pm. Boogie is the kind of high-profile debut that D&Q could have hosted anywhere, but Boogie is a natural fit for Short Run: it shares an ingenuity and an exuberance with the festival.

Ayuyang, the daughter of Filipino immigrants, grew up in Pittsburgh with a large and boisterous family. Boogie is a coming-of-age story, a story about the challenges and rewards of family, and a tribute to the glamorous and goofy world of dance entertainment — particularly movie musicals and reality dance competitions. Perhaps that last element sounds out of place in a synopsis, but it couldn't feel more right on the page. Thematically and artistically, Boogie is a triumph; it brings the energy and joy of a truly great musical to the comics page.

Ayuyang's colorful, vibrant comics bear no relationship to the darkly cynical autobiographical comics of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Her panels aren't often separated by gutters, and panel after panel clambers onto the page, resulting in a bright parade of color and emotion. With no panel borders, elements from previous panels leak into the story and characters seem to be mingling together without regard for time or space. It feels like a story told by a narrator who is so excited that she jumbles elements of the story together, leaping back and forth through time, but Ayuyang retains total control over every element of her craft. She knows exactly what she's doing.

The book begins with a wide, sweeping look at Ayuyang's suburb from miles in the air. The greens are sketched in with what appear to be colored pencil. Our perspective is closing in on Ayuyang's house, a respectable two-floor middle-class home.

"From afar, it looks perfect," Ayuyang tells us in a caption.

She closes in on the front door. "But if you look closer, things aren't always what they seem."

Then a closeup of the pebbled green glass of the front door. "Beyond this door," Ayuyang warns the reader, "lies a story of dread and woe, despair and sadness."

Turn the page, though, and we see a young Ayuyang playing in a warm and cozy home. Toys are splayed all around her. "I'm kidding," she writes. "It's just a mess. Mostly mine."

The characters in Boogie certainly do confront pain and heartbreak, but the story is a happy one. Ayuyang is a cheerful narrator — even as she describes her addiction to Facebook and the conflict of reality smashing up against the monolith of fantasy, she's inclined to be a positive and generous host.

Boogie is a series of anecdotes that accrue together into something much bigger than the sum of its parts. Not every trick in the book works — a major time jump near the middle of the book feels very abrupt, and it takes the reader a few pages to catch up to all the developments in Ayuyang's life — but every trick is attempted in good faith, with an excitement for the medium that is infectious.

It's hard to convey the precision of a good dance number to comics, and Ayuyang often is forced to relate whole dance routines in one or two wavy lines and a couple of distorted figures. But it's hard to imagine any cartoonist being able to transfer the complexity of a densely choreographed dance number with ink and paper. What Ayuyang fails to report in accuracy, she more than makes up for in enthusiasm. Short Run is where Seattle's youngest and most promising cartoonists go for inspiration, they would be well advised to pick up Boogie and learn at Ayuyang's (dancing) feet. Comics could use a lot more of this color and life and energy.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Finding Nirvana

"Aberdeen is what you would call a shithole," Belgian cartoonist Gerrit De Bremme writes late in his debut comic Kurdt. "The economy is dead and there is not much happening." De Bremme has traveled from Europe to the Pacific Northwest in search of Kurt Cobain's birthplace. He's not a Nirvana superfan, but he's fascinated by the icon that Cobain has become, and he's hoping to find the humanity at the heart of the rock-star narrative that's grown up around the Nirvana story.

Kurdt is an impressionistic travelogue comic — much of it seemingly drawn from photoreference — with De Bremme's thoughts overlaid in a series of captions. It reads like a dreamy, earnest documentary, and part of the thrill for Seattle audiences is seeing De Bremme's interpretation of local landmarks like Gasworks Park, Green Lake and the seediness of Aurora Ave. The book is illustrated in a heavily polarized black-and-white, with panels that resemble overexposed photographs. And De Bremme has doused each page in moody shades of blue, reflecting his own state of mind and his interpretation of the rainy Pacific Northwestern climate.

At times, Kurdt gets a little too earnest, and De Bremme allows himself to collapse into cliche. (The most egregious line: "Now I'm back in the Emerald City, ready to tackle that big grungy elephant in the room.") These lapses in narrative discipline are common enough in books about iconic celebrities — there's not much substance to grab hold of in the entirety of Cobain's 27-year existence, so writers tend to get a little too vague, a little too grandiose, in their interpretations. When De Bremme stares directly at Cobain, he's furthest from understanding him.

But Kurdt isn't really about understanding Cobain any better as a human being. It's about how the places we're from shape us, and how we either grow beyond those formative experiences or we stay rooted in place forever. It's about traveling halfway around the world for basically no good reason and trying to make the most of it. It's a tone poem about De Bremme finding his place in the world, even in a place that's as far from his home as is humanly possible.

Thursday Comics Hangover: More than Zero

Originally published back in 2000, Karl Kesel and Tom Grummett's Section Zero was an adventure comic that paid tribute to some of Jack Kirby's greatest creations — primarily the Challengers of the Unknown and the Fantastic Four, though with some Kamandi and Demon thrown in for good measure. The limited series, about a secret team of supernatural explorers employed by the United Nations to investigate mysterious happenings, was packed full of the stuff that made Kirby's comics great: wild character designs, a breathless pace, and plenty of action. But Section Zero was caught up in a publishing implosion and the inaugural adventure was never completed.

Books that are canceled in medias res are a risk of reading serialized comics. They don't happen too often, but every once in a while you'll have your heart broken by a story that never ends. The heartbreak of Section Zero, though, was that Kesel and Grummett seemed to be having a blast with the series. You can tell when a creator is totally invested in a book, and Section Zero was clearly a labor of love.

This year, Grummett and Kesel launched a successful Kickstarter campaign to publish the first three original issues of Section Zero, and then to complete the story they started nearly two decades ago. I backed the campaign and just received my Section Zero: There Is No Section Zero hardcover book in the mail this week. It's a gorgeous book, even including a bright green cloth bookmark for extra classiness.

I'm happy to report that most of Section Zero's early issues have aged quite well. The team, featuring an unflappable leader, a grey alien named Tesla, a sea monster named Sargasso, and a kid with a cursed tattoo that turns him into a bug for a day at a time (he's gloriously code-named The 24-Hour Bug) is about as comic-book-y as they come.

And when it comes time to incorporate the new material into the book, Kesel and Grummett wisely don't pretend nothing has changed: instead, they skip the narrative ahead to 18 years later, following the characters over almost two decades of change. The new material — in conjunction with a framing device that shows off Section Zero teams of the past — allows the creative team to provide meta-commentary on adventure comics in history. They're not fighting the past, or living in the past, they're in conversation with themselves in the past, deepening and adding new layers to the story.

Only one main character — unfortunately you could argue the main character — seems unfortunately dated. With his cool-guy sunglasses, his edgy katana, his unfortunate facial hair, and his brown leather jacket on top of a full spandex outfit, Sam Wildman — the roguish Harrison Ford-type of the cast — feels pulled right out of the doldrums of late-1990s hero comics. The book is actively better when he's not in it, pushing his edgy vibes on everyone.

But what's a team of adventurers without at least one annoying character (looking at you, Fred from Scooby Doo) to make everyone else more relatable? Collected in one place like this, with the span of time incorporated into the narrative, Section Zero is like no other adventure comic on the stands. Here's hoping that Grummett and Kesel can keep telling these stories for as long as they desire.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Ban men

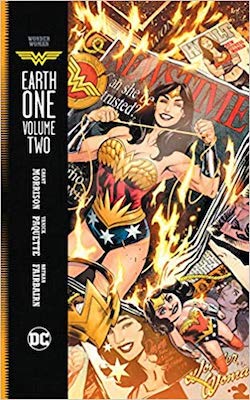

All of a sudden, and presumably thanks in part to the smash-hit movie, Wonder Woman comics are exciting again. Seattle author G. Willow Wilson is preparing for a splashy run on the character next month, and even before that announcement, the regular Wonder Woman title saw a notable increase in quality.

And last week, DC Comics published the second volume of their Wonder Woman: Earth One series, written by Grant Morrison, drawn by Yanick Paquette, and colored by Nathan Fairbairn. The Earth One series is intended to provide a new-reader-friendly, straightforward high-quality origin story for DC's most recognizable characters, and it's not even necessary for readers to be familiar with the first volume of the Wonder Woman book to jump into the second.

Paquette and Fairbairn pair seamlessly to make this Wonder Woman visually distinctive. Morrison famously bragged in the round of publicity for the first volume that the book is designed to be almost entirely free of phallic imagery, but Paquette is doing much more than just embracing yonic symbols. Every page of this book is gorgeously designed, with intricate panel borders and involved layouts that still guide the reader across the page. Fairbairn's palette is heavy on regal reds and golds and deep blues — the color of Wonder Woman's costume becomes the basis for her entire world.

The second volume of Wonder Woman: Earth One is very interested in classic superhero comic tropes. The book opens with a flashback to a Nazi superwoman's attempted World War II invasion of Wonder Woman's home, Paradise Island. Rather than imprison the Nazi, the Amazons decide to retrain her into decency, with some rather morally dubious mind-control techniques. This was a common occurrence in pulp fiction like Doc Savage and in early Superman stories, but modern audiences, with a more nuanced understanding of free will, are likely to be creeped out. This is part of the design.

And Wonder Woman herself is trapped in a battle of wills with a pick up artist who wants to dominate her spirit. Morrison blends the traditional (a very straightforward idea of submission and dominance) with the modern (the antagonist is a very Gamergate-style men's rights type.)

This book offers a potent blend of old and new, hopeful and cynical, square and progressive. Like most of the best Wonder Woman comics, it will likely unsettle readers of traditional masculine superhero comics. They'd better get used to it: there are a lot more powerful women coming their way. Personally, I'm excited for some more women-led creative teams to take up the charge.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The color of adventure

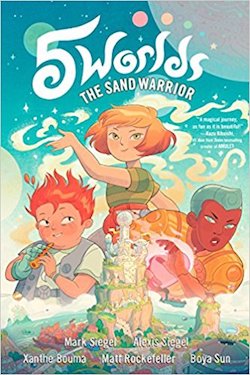

The comics industry is twisting itself up into a knot over the fact that kids aren't reading superhero comics. Even though young people are attending superhero movies in sick-making numbers, they're not buying into the comics that serve as the basis for those movies.

But I find it hard to get too exercised over this "crisis." Kids are reading comics, probably in greater numbers than they have in decades. They're just reading about different kinds of heroes. These heroes look more like the kids of today — diverse, confident, proudly imperfect — and they don't carry any of the odd baggage that has accrued around superhero stories for the last six decades.

Early in The Sand Warrior, Oona finds herself on a predestined mission to reignite ancient beacons spread across five war-torn planets. She teams up with a space athlete and a strange little outcast to save the galaxy.

Creator-wise, it's hard to tell exactly who did what in the 5 Worlds series. It's written by brothers Alexis and Mark Siegel, but three illustrators are credited for the art: Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Whoever actually drew the thing deserves a ton of praise: the art is cute without being cloying, and imaginative while still being thoroughly relatable.

But the real genius here is the coloring: using a palette of pastels and gentle earth tones, these books are dreamy and warm and unlike all the other fantasy books on the shelves. A giant sand creature near the end of the first book is framed against a dusky sunrise and a gloomy moon, adding to the reader's sense of wonder. Whoever is responsible for coloring this book is breaking new ground in adventure comics; the superhero publishers should be ripping them off as shamelessly as possible.

Occasionally, the 5 Worlds books grind to a halt to provide exposition that will move the story forward for the next 30 or 40 pages. These info dumps are a bit too thick for their own good. Ooona says to someone early in the first book, "But...but I thought the Sand Castle and the Flying Fortress hated each other!" He replies,

Plumb visited with Domani diplomats but he was secretly teaching me. I came to understand there is something rotten in the heart of the Fortress these days! Toki stands against lighting the beacons! I escaped to continue my training because I believe lighting them is the right thing to do.

That's a lot of telling. Showing this character's backstory probably would have added a lot of pages to the book — at about 250 pages each, these are not exactly slim — but they would have made the story feel a little more organic.

But kids love exposition as long as it leads somewhere good. Oona's quest is perfect for young readers: she travels from planet to planet, lighting the way for a kinder, more inclusive future. You can keep your superheroes; she's just the hero that we need right now.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Women strike back

It was a jam-packed new comic book day at comics shops yesterday, with everyone rushing to read the first issue of Tom King's superhero-mass-shooting crossover Heroes in Crisis and the latest issue of the Watchmen crossover series Doomsday Clock. Those are big, serious adult superhero stories — you can tell by all the blood and dead bodies and nudity — though neither of them are anywhere near as moving as Chip Zdarsky's final issue of Peter Parker: The Spectacular Spider-Man, which is number 310 in the series.

If you enjoy the character of Spider-Man, I can't recommend this issue enough. Zdarsky perfectly nails down what makes Spider-Man so fascinating: he's funny, but he's also incredibly annoying. He's kind-hearted, but he's also a little bit obsessive. He finds ways to help people in need that go far beyond the standard superhero fare, and this story — which you can read without first reading any other issues of the book — highlights both his strengths and weaknesses in turn. I wish more superhero comics were this tightly constructed, and moving, and fun.

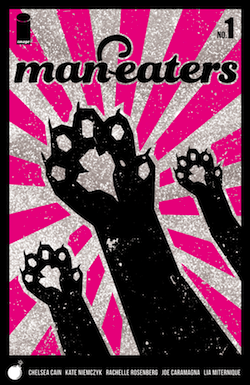

But the highlight of the week for me is the first issue of Man-Eaters, a new series by Portland author Chelsea Cain. Illustrated by Kate Niemczyk and colored by Rachelle Rosenberg, Man-Eaters is the sci-fi story of an epidemic that finally makes men as terrified of women as women have traditionally feared men.

If that sounds like a horror comic to you, you should know that Man-Eaters is very funny, too. Cain and Niemczyk are remarkably inventive here, telling the story through traditional narrative comics and graphs and photorealistic effects and other wild experiments in visual narrative. There's a lot of exposition here, but the storytelling is so exuberant that none of it feels like a chore to read.

Cain seems to inherently understand what it is that makes comics so great: unlike novels, comics can relay a tremendous amount of information in a single image that takes a second or two to read. Niemczyk and Cain are so good at relaying that information that a reader might have to force themselves to go back and read the first issue several times, just so they can fully realize how information-dense it is. In a week where superhero comics are trying (and in some cases failing) to address very real issues like trauma and the impact of violence, Man-Eaters is tackling misogyny head-on, and making it look effortless.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Quick, to the Bat-pole!

All anyone on the internet can talk about right now is an impossibly famous, wealthy, and powerful man's penis. The revelation has inspired crude jokes, boundless speculation, and more than a little controversy.

I'm talking, of course, about Batman.

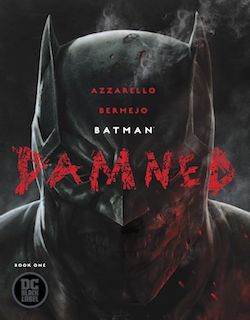

The first issue of the three-part Batman: Damned series was published yesterday, and for several panels in which Bruce Wayne wanders around the Batcave nude, artist Lee Bermejo clearly illustrated the contours of Wayne's penis. Before you start worrying about the children, you should know that this comic is intended for adult audiences. Damned is the first original series to be published by DC Black Label, a new imprint allowing for idiosyncratic takes on classic DC Comics superhero characters.

The fan response to Batman's wang was so loud and so unhinged that DC Comics apparently edited the offending unit out of the digital version of the comic. This means that DC could perform the same edit job on future editions of the comic, so the copies of Damned that are on the shelves right now might be the only chance readers will ever get to see Batman's genitalia in an official DC Comic. For whatever that's worth.

Damned is a horror story in which Batman may have killed The Joker. (Our hero, having suffered a traumatic injury on the night that the Joker's body was found, doesn't remember what happened.) All sorts of DC Comics dark fantasy characters show up including John Constantine, the Enchantress, Zatanna, and a personal favorite of mine — Deadman. It's pulpy fun that feels reminiscent of those early days of Vertigo, when Superman would wander into a Sandman comic and try to grit his teeth and ignore all the weird shit happening around him.

The big selling point here is Bermejo's painted art, which portrays Batman as a giant slab of beefy eroticism. It's like what would happen if Tom of Finland illustrated the comic adaptation of a Batman movie. Brian Azzarello's script establishes a large cast of characters and a good central mystery, although there's way too much narration on just about every page. Bermejo can relay more information in a single panel than a hundred captions. ("He's running for his life," reads a single caption in a panel depicting Batman running for his life.)

The most exciting part of Damned, for me, has nothing to do with Batman's penis. It's the format of the book. Damned is presented as a graphic album: for $6.99, it's bigger and wider than the average comic, it's printed on better paper, and it's squarebound. It's a format that demands the reader take the art seriously, and Bermejo makes the most out of the high-definition treatment.

Despite Damned's early in-comic tributes to classic Batman tales The Killing Joke and The Dark Knight Returns, I don't think it will take a place alongside those books as an all-time great Batman story. Explaining Deadman — a circus performer who died and is now spending his afterlife hunting down his own murderer by possessing innocent bystanders — to a general audience seems like too much of a lift. But for hardcore readers who like to see different interpretations of their favorite heroes, Damned is an interesting, uh, package.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Wherever you go, there you are

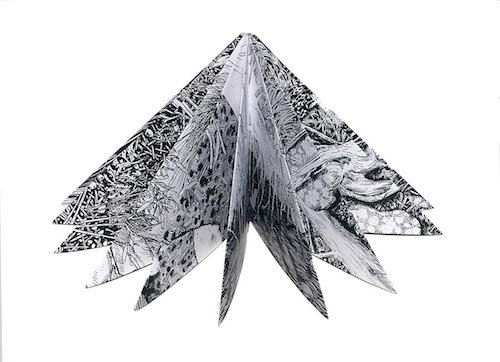

Short Run cofounder Eroyn Franklin's latest comic, Vantage #3, comes in a triangular envelope that is illustrated to look like a yurt. Inside the envelope, Franklin explains that this issue of Vantage is a record of her time at a monthlong residence at Caldera Arts in Oregon.

Franklin hiked a lot in her time at Caldera, and during those hikes she would stop and look straight ahead, and then at the ground beneath her. Vantage captures those two views in a beautiful little triangular minicomic that the reader can unfold and read in several different ways.

As a viewer, you have a choice. You can pull back the corners of each page to unveil a tableau that Franklin witnessed — a creek in a densely wooded area, or a waterfall, or a crater lake. Or you can leave the book in a kind of free-standing Christmas tree shape, which Franklin calls "comic sculpture."

No matter how you choose to read Vantage, Franklin's detailed black-and-white illustrations will move you. The conceit of combining a panoramic view with a close-up of the ground beneath her feet — the land ahead, the land below — is especially moving. Who hasn't been surprised by the beauty of nature, only to look down to make sure they're still connected to the earth?

With no words on the actual comic, Franklin manages to portray one of the most complex joys of nature. Even the loftiest tree still has a complex system of roots to keep it connected to the dirt below. Amateur hikers might value those vistas over the ground underfoot, but they're missing the point. There's just as much complexity — and beauty — under our feet as there is in front of our faces. It's all one piece.

Thursday Comics Hangover: By the time I get to Arizona

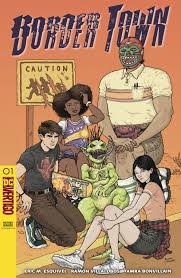

Monthly serialized comics are a relatively fast-moving medium. If a team on a book is really humming, they can create a title and get it on the stands in a matter of months. That seems to be the case with Border Town, a new Vertigo title whose first issue was just published yesterday. Written by Eric M. Esquivel and illustrated by Ramon Villalobos, Border Town feels as current as the day's headlines — for better and for worse.

Pretty much every page of Border Town references some aspect or another of the Trump Administration. The first page features a bunch of xenophobic white Arizonans firing machine guns into the air and shouting "MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN, MOTHERFUCKER!" But in Border Town, current events are pumped up and made into monsters and paraded through the streets. The town of Devil's Fork, Arizona is being haunted by modern American specters: a white woman is terrified by a figure that looks like a black teen, a man runs from a green-skinned ICE agent, someone else recoils from a giant "tiki-torch Nazi" with sharp teeth roaming the streets. It's the American nightmare in a Halloween mask — or maybe with the mask removed.

None of this relevancy would matter if the comic was ugly. But Villalobos makes reading Border Town a pleasure. He's from the Geoff Darrow school of comics art — the noodly, hyper-detailed work that rewards repeat viewing. (The first issue features cameos from Sandman and an especially beloved Superman story.) And colorist Tamra Bonvillain is doing some stunning work here — the color pallette of the book tracks a single day, from night to dawn to noon to dusk to night. The light in Arizona glows warmly, but all those oranges and reds and blues could just as easily represent a bruise.

It remains to be seen if the plot of Border Town will rise above some pretty standard "there is a pierced vale between this world and the next" supernatural potboiler drivel, but the quality of the art in the book, and the cleverness with which the creative team addresses contemporary topics, will keep me coming back regardless.

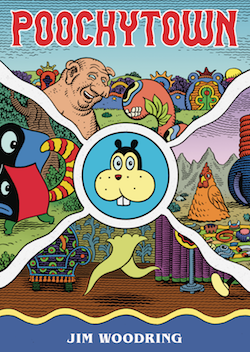

Thursday Comics Hangover: Won't you take me to Poochytown?

Jim Woodring isn't just creating a new world in his wordless Frank series of comics — he's designing an entirely new vocabulary. The Frank comics take place in the Unifactor, a densely illustrated cartoon world with its own laws and distinctive life forms. The main character is Frank, a generic cartoon character (Is he a cat? A mouse? Why is his face so...scrotal?) who comes across as a Chaplinesque innocent — albeit one with a vicious mean streak.

Every new Frank book changes the Unifactor in some way or another, adding a new element to the formula and playing out the scenario to see what happens. In the last book, Fran, Frank met up with a feminine version of himself, and the resulting interactions nearly destroyed the Unifactor.

In Woodring's latest volume, Poochytown, Frank's sort-of pets Pushpaw and Pupshaw climb into a higher plane created by a deranged musical instrument. Without his companions, Frank becomes lonely and eventually befriends his longtime enemy, the unsophisticated and hideous Manhog. The adventure involves a horse that chews off Frank's limbs, a visit to a location that resembles Woodring's studio, an out-of-body experience inspired by someone battering their head against a locked door, and one of the most heartbreaking emotional turns in the series thus far.

It's possible to read the Frank books as the comics version of silent movies — Woodring decorates all the stories with slapstick and visual gags and amusing side-quests — but they are seething just underneath that cartoony surface. Woodring is exploring primal concepts like religion and consciousness and community.

And while the surface elements of the Frank comics are just as beautiful as ever (Poochytown features some of the most breathtakingly intricate pages of Woodring's career, which is really saying something,) that deeper existential level feels as though it's growing more frenetic with every new volume. Poochytown enjoys the same moseying pace as the rest of Woodring's stories, but the inquiries he's making here on a philosophical level feel as dark and cutting as anything he's ever written.

No prior familiarity with Woodring's work is necessary to enjoy Poochytown, but after reading the book you might feel a certain anxiety roiling deep inside. That's not a mistake. More than any literary novel I've ever read, Woodring's Frank comics accurately portray the stresses and disappointments and horrifying wonder of what it is to be alive. And as being alive becomes more and more terrifying in the early part of the 21st century, Woodring's art reflects that terror right back at the reader.

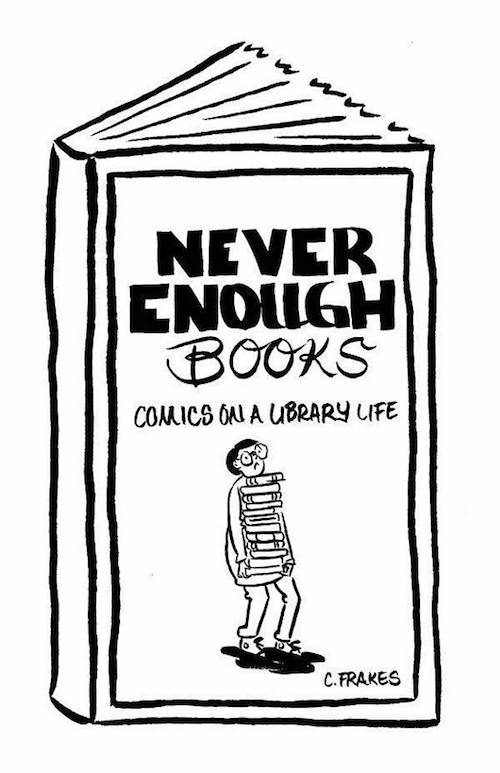

Thursday Comics Hangover: The cartooning librarian

To a lot of bookish nerds out there, Colleen Frakes is living the dream: she's a librarian who draws comics in her spare time. And while Frakes is always very present in her work — seriously, read her memoir Prison Island — I've rarely seen her discuss her bookish life in her work. I've always wanted to read that book.

So when I was browsing the local cartoonist shelf at Phoenix Comics recently and I found a mini comic by Frakes titled Never Enough Books: Comics on a Library Life, I didn't hesitate for a second. I bought the book and read it immediately. (To be clear, Never Enough Books is only new to me; the indicia says it was first published in fall of last year.)

Never Enough Books is a collection of short autobiographical essays in comics from explaining Frakes's lifelong love affair with books. From her childhood as a self-described "'spend every recess in the library' type indoor kid" to her first librarian position at the Center for Cartoon Studies, Frakes explains what books have given her — and done to her.

If you grew up as a bookish nerd, you'll see yourself in these pages. Frakes is a genial host who romanticizes books while keeping her own mildly misanthropic tendencies in full focus. No, books can't cure everything. Yes, books do make everything better.

My one quibble with Never Enough Books is that it feels like a 90-page graphic novel crammed into a 12-page mini comic. I'd love to read a whole comic autobiography about becoming a librarian — perhaps with interesting moments in library history interspersed in the personal narrative. So far as I know, no cartoonist has ever made a book like that. The world is ready for the comics version of Nancy Pearl, and Frakes couldn't be more suited for that position if she were engineered in a laboratory.

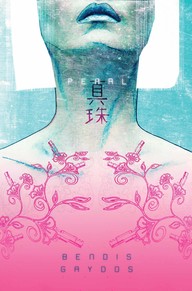

Thursday Comics Hangover: Pearl, with irritation

Brian Michael Bendis's creator-owned comics are often very strong, but they're also often plagued with extensive publication delays that leave audiences annoyed. (What's up, Scarlet? It's remarkable that a writer as prolific as Bendis — he often juggles four monthly titles, in addition to special projects and a teaching gig — falls down on the job as much as he does.

The shame of it is, these books are usually his best work. Scarlet, in particular, started out as a great Occupy-themed commentary on income inequality. Then it was delayed so long that it felt like a timely statement on police shootings. And who knows how many other hot-button issues it will glide by on its glacial pace to completion?

Honestly, I wish I didn't have to begin this column with a huge asterisk, but Bendis has failed so consistently to finish what he starts with his creator-owned property that buyers should beware.

So with all that in mind, I like the first issue of Bendis's new creator-owned book with Michael Gaydos, Pearl. It's the story of a gifted young tattoo artist who accidentally becomes the pawn in a seedy underworld power play. The book opens in a San Francisco food truck parking lot, when a young man notices the gorgeous spider tattoo on Pearl's wrist. Violence ensues soon after.

It's pretty obvious that the book is going to be an investigation of tattoo culture. And it's also obvious that the creators have done their research; the credits list Diego Martin as "tattoo designer." This seems like a natural match with comics, which is the only medium that can really engage in a conversation with tattoo artistry.

Gaydos's art is becoming more and more minimalist as the years continue. He's one of those cartoonists who can relay a complex emotion — say, arousal combined with wariness — in something like five lines. And in Pearl, he's playing with color in some very interesting ways. When the food truck is attacked by gun-wielding mobsters on motorcycles, the book's whole color palette shifts from a slick damp-city-at-night sheen to a day-glow mix of sickly greens and muddy reds, with bits of tattoo flash added in the margins for additional emotional intensity.

As perfectly as the coloring captures the emotional intensity of that sequence, I do wish that Gaydos had been a little more specific in his action sequences, though. In the end, I have no idea who got shot by whom, aside from the main characters. Did everyone else die? How many people were involved? It's very unclear.

For those of you who take a chance on Pearl, it's very likely that you'll enjoy what you read. Even if the plot doesn't advance very far by the end of the issue, Gaydos's artistry alone is very gawk-worthy. But will there be a Pearl issue # 2 on comic shop shelves before we all die in a Trump-inspired nuclear holocaust in the late summer of 2020? I can't confidently place a bet either way.

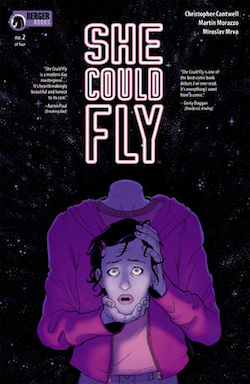

Thursday Comics Hangover: Two number 2s

Halt and Catch Fire creator and showrunner Christopher Cantwell has a new comic called She Could Fly. The story begins in very familiar territory for a comic — in a world like our own, a young woman gains the power of flight — but the premise immediately goes south when the woman explodes in midair. Nobody knows who she is or how she could fly or why she exploded. Internet conspiracy theories sprout overnight like so many blackberry bushes.

Luna, the star of She Could Fly, is obsessed with the flying woman. In the second issue of the book, which came out yesterday, Luna's guidance counselor says "I want you to give this flying woman a rest." Luna doesn't listen to her — and for some reason, the guidance counselor has the head of a cat and a human body.

Luna, it seems, is hallucinating. She imagines demons attacking her. She imagines becoming a demon (sample dialogue: "I AM EVIL! I AM EVIL! I AM EVIL! I AM EVIL!") and she keeps digging deeper into the story of the flying woman. Meanwhile, a moustachioed rogue agent is also looking for the truth. The up-and-coming cartoonist Martin Morazzo renders Luna's reality with a high level of detail, making it even harder to tell the difference between what's real and what's fictional in Luna's world. Halfway through She Could Fly, I can't tell you what the book's about. But I can tell you that it's going somewhere interesting.

Speaking of second issues, the second issue of Chew artist Rob Guillory's new book Farmhand was published yesterday. Where She Could Fly continues to complicate the psychological layering of the series by obfuscating the narrative, Farmhand introduces characters and tensions with a refreshing directness.

Farmhand is the ultimate body horror comic: it's about a scientist who figures out how to grow new human body parts on trees. The technology, at first, seems like a godsend. In the second issue, a disfigured woman grafts a plant-based nose onto her face. But everything is more than a little creepy: a bush full of human hands isn't exactly a comforting image.

Guillory is setting up Farmhand to be a drama between an estranged son and his father. (The family tree jokes write themselves.) But there's also some fascinating depictions of addiction and recovery, as well as more than a little economic anxiety. It's the details here that make Farmhand so enjoyable. Even though Guillory is great at getting to the point in a hurry, he understands that we have to take the long way around a story every now and again.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Superman runs down the clock

We are now halfway through Doomsday Clock, the 12-issue Watchmen...sequel?...written by Geoff Johns and drawn by Gary Frank, and I still have no idea what to think of it. Is it fan fiction? Is it an earnest attempt at a sequel? Is it supposed to be funny?

It would be easier to tell if Doomsday Clock had a consistent tone. This is a book that completely misunderstands Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's postmodern riffs on superheroes by reveling in their "coolness." The most recent issue features a Watchmen character massacring DC super villains in a scene that is clearly supposed to impress readers with its badassness. Previous issues featured a resurrection from the dead that is just as cheesy as a plot twist you'd find in one of the old cliffhanger serial films Ozymandias mocked at the end of Watchmen.

In the end, of course, it doesn't matter. Watchmen will still be there, long after Doomsday Clock is forgotten. And Watchmen isn't even as good as you remembered it, anyway. But the fact that it's taken six issues at $4.99 a pop to get exactly nowhere in the story is downright criminal.

"I believe in the power of these icons. I believe in the power of hope, and optimism," Johns told SyFy when Doomsday Clock was announced. That doesn't reflect anything I've seen in the first six issues of Doomsday Clock.

Surprisingly, another DC Comic is honoring exactly those values. When writer Brian Michael Bendis jumped ship to DC after umpteen years of exclusivity at Marvel Comics, readers expected Bendis would take on a street-level hero like Batman as his first project. Instead, he decided to write Superman. And, honestly, Bendis's Superman is exactly what the character should be: powerful, optimistic, friendly, and warm.

My one regret is that Bendis launched his time on Superman with a plot that involves yet another mysterious character from Krypton's past. As I've written before, the sci-fi trappings of Superman are the least interesting part of the character. Nobody has ever given a shit about Krypton.

People read Superman comics for the same reason they watch Mr. Rogers: they want to believe in a morally good universe, one in which right triumphs over wrong because it is right, not because it's strongest. If Bendis can maintain the essential decency of the character in months to come while telling stories that get to the heart of Superman's appeal, odds are good we'll be remembering Bendis's Superman run long after the mess that is Doomsday Clock has faded from our memory.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Done in one

You'll rarely encounter a truly conclusive conclusion in superhero fiction. Everything is endlessly serialized, presumably under the assumption that a too-pat ending will inspire readers to drop off a title. All this inconclusiveness gets tiring.

And in an age in which every superhero story is collected in a trade paperback, comics have gotten even more endless. Decades ago, when a creator was late with a title, editors would reach into their back catalogs and pull out a one-shot story — meaning one with a beginning, a middle, and an end — they could plug into the scheduling hole. Often, these stories served as training wheels for up-and-coming talent, and many of them were...well, not good.

But every once in a while, a good one-shot story gets to the heart of a superhero, explaining in a kind of mission statement why the character matters and providing a blueprint for creative teams for years to come. This week, DC Comics published one of those rare comics, in Wonder Woman issue 51.

The basic premise is not original: Wonder Woman sends a criminal to prison, and then Wonder Woman continues to visit the prisoner over the span of months and years. At first, the prisoner is aggressive. Over time, their relationship gets more complicated. Author Steve Orlando isn't reinventing the wheel, here.

But unpredictability is not the charm of the story. Orlando's script is warm and patient, and artist Laura Braga deftly straddles the line between superhero comics and the expressive character work. You know how it's going to end, but you can't wait to get there.

Way too often, Wonder Woman is presented as nothing more than the female version of Superman, or a generic powerful hero who happens to be a woman. Braga and Orlando in one issue manage to explain what it is that makes Wonder Woman a unique character, and to establish a precedent for creators in the future. She doesn't just vanquish crime; she rehabilitates criminals. Hopefully, Seattle author G. Willow Wilson, who recently was announced as the new writer on Wonder Woman, will expand on the themes of this story, to give a new purpose to the never-ending adventures of Wonder Woman.