NanoWriMo Week 2: It doesn't matter how you feel

So, how's progress? If you're on track, and getting your nut in every day, you should be about 10,000 words today. If you've cracked that milestone — congratulations! That's huge. If you haven't, don't despair. Buckle down over the weekend and get some hours in. This is the time to make it happen. Your book can't be read until you've written it.

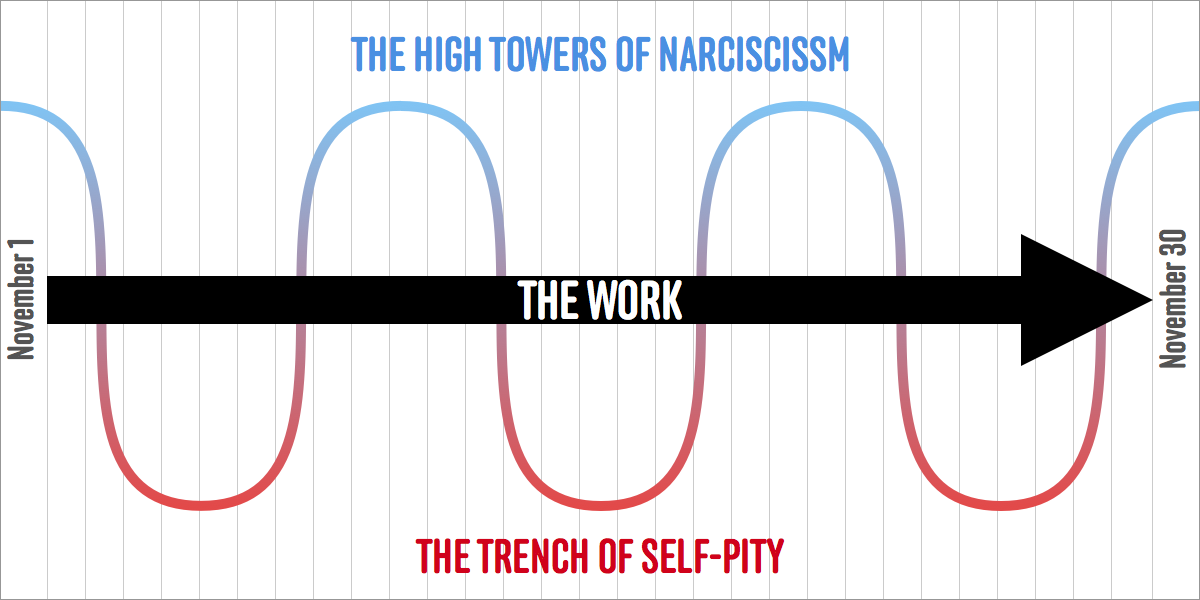

Today we're going to cover the sine wave that is a writer's mood when penning a novel. I even have some graphics! Let's start with the straight line down the middle:

That's you, writing. Imagine this is your timescale, in this case, one month (although, it can also be months or years, the process is the same). November 1 is to your left, and November 30 to your right. That black line across the middle is your work, as you forge ahead. This is how we think about writing, right? We'll apply ourselves and work diligently and achieve our goals in a straight line.

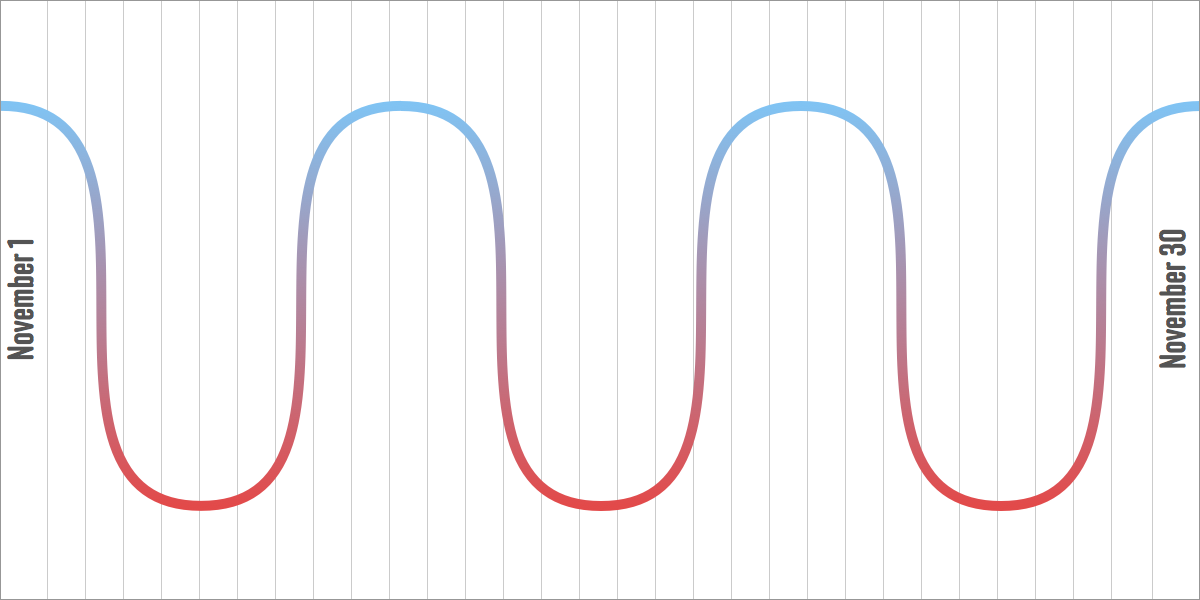

But, as humans, we have these things called feelings. They're pretty useful, but sometimes get in the way. Like, for example, when we're writing. Sometimes we feel great about what we're writing, and sometimes we feel awful about what we're writing. In fact, that emotion goes up and down with such regularity, that we can almost plot it. Simplified, it looks like this.

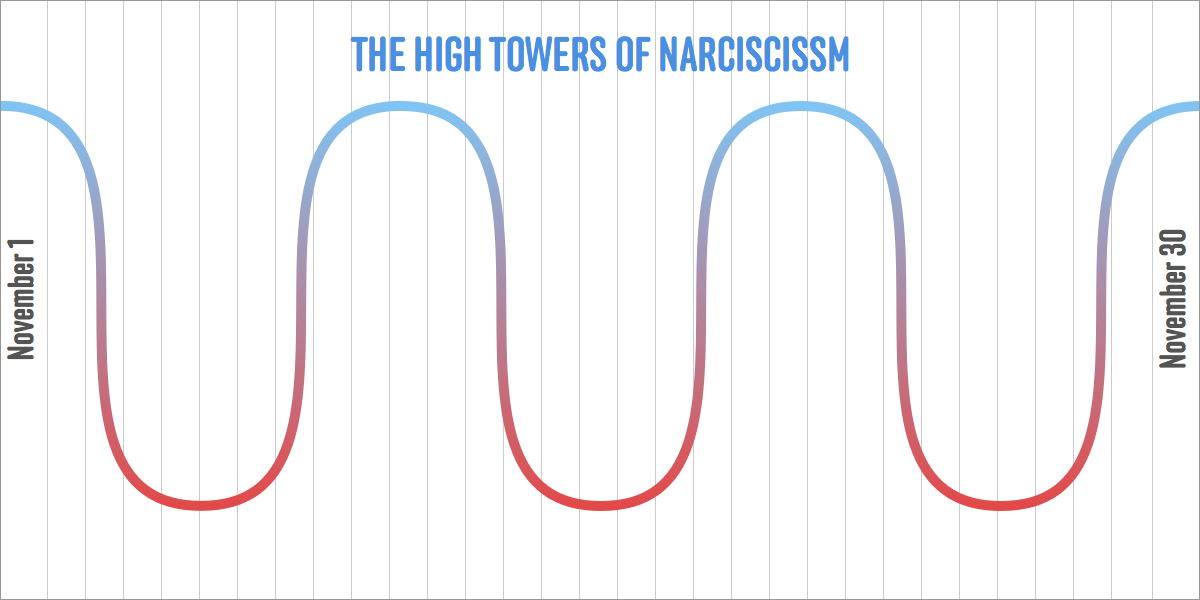

At the top, we're sure that what we've written is the greatest piece of writing the world has ever seen. In fact, they should just award us all the prizes right now, a Nobel, a MacArthur Genius, some of the more obscure ones, to boot. They'll make us the first photographic portrait cover on the New Yorker. MFA programs will start courses on us. Because, they'll see, no other human has, with such precision and clarity articulated the exact solution to every problem in the world, like we have on these ever-so-satisfying pages. We call this the:

And high they are. And narcissistic they are. But, that's okay. This feeling is delusional, but it is a true motivating factor. Nobody else will advocate for your unwritten book. You need you to be excited about it. You are its champion. You are, literally its raison d'être. So let's not take our cheerleading as literal truth, but let's acknowledge its purpose in our life, and let us be motivated, excited, and buffed by it.

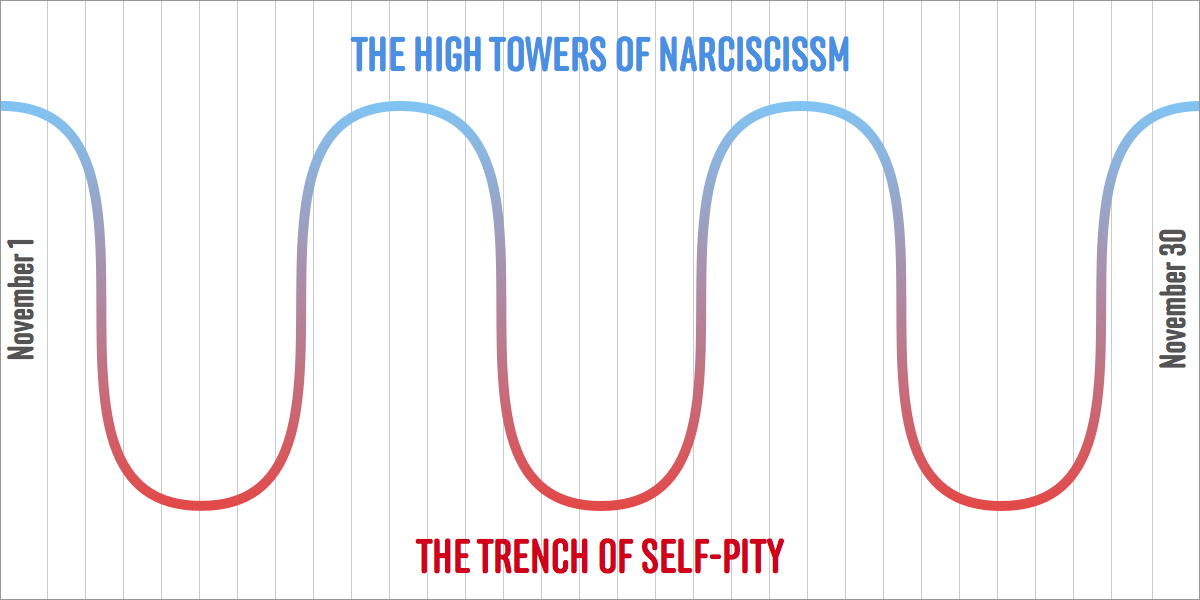

As nice as the high towers of narcissism are, they are fleeting. Before too long, we're falling down the trough, across that line of our progress (say hello on your way down!), and we find ourselves wallowing in:

Oh god, this is the worst place ever. We're the worst writer the world has ever produced. What ridiculous fools we've been to think we can do something so asinine as write a book. Can you believe our hubris? Our idiocy? How trite every sentence is? How pathetic every metaphor? We should just crumple this piece of crap and walk away, never to write again. In fact, the world is literally demanding it of us, standing on our doorsteps waiting for us to just hand them our resignation from ever attempting to do art again. They have formed committees to search and delete all text we have ever put in the world, and President Obama has called for a congressional investigation into whoever the hell taught us to read in the first place.

Ugh. The trench is the worst. It's a pity party all the time, and nobody knows how to throw a pity party like a person trying to be creative and feeling like a failure. However, it's ironic, but true: we need the trench. The trench is what separates you from a true narcissist, someone who is truly delusional about their work. The trench sucks, but it is activated by that part of your brain that will later be a good steward and editor to your work. It is the part that is activated by wanting to be good. And we want to be good writers, yes? We want people to read our work and say "this book is so good, because that person is a really fine writer."

But the feelings of the trench should be activated later: when we're editing, and thinking about our work critically. At this point, the appropriate response is to say "Oh hey, look at that, I'm walking through the trench and I feel shitty. Guess I'll just get my words in anyway."

This is where it all comes together. Because that sine-wave is your feeling, but it's not the work. The work continues, like this:

Notice one thing about the black line: it doesn't change. When I'm sitting at my desk, and I'm triumphant in the high peaks of narcissism, I celebrate it by getting words out of my head onto the page. When I'm wallowing in the trench of self-pity I flop around in its cold humidity by putting words on the page. And when I rise out of the trench and can once again see the horizon, I rise while I write, and when I fall from the towers, I fall while I write.

And you may not believe me what I'm about to tell you, so you're just going to have to write through your own sine-wave and see this strange effect for yourself: you cannot discern a difference between your writing when you're feeling great about it, and your writing when you're feeling terrible about it. The writing through it all is consistent.

Your feelings are needed, but they are unreliable narrators to the quality of the words you are putting onto the page. Your job, during November, is only to get words on the page, not decide if they are good or not. Let your feelings ride the wave (you can't stop them, after all) and focus on your task of getting your words in. One word after the other, one sentence after the other, one paragraph after the other, one page after the other.

And when you've crossed that finish line, and got your words in and you're reading back through them, see if you can find the tower and the trench in the words themselves. If you can, tell me I'm wrong. I'm laying odds they'll be as invisible and fleeting as feelings in our past always are.