The algorithm method

Amazon.com has come a long way. They’ve been in business for two decades now, moving billions of dollars of merchandise around the world, harvesting untold amounts of information from their customer transactions and searches, collecting tens of billions of pages worth of customer reviews on products, and investing tens of millions of employee work-hours into tightening the gap between customer desire and customer satisfaction. In many ways, the culmination of what Amazon sought to do with all that data is now made physical, in the form of a brick-and-mortar store, Amazon Books, in a University Village storefront formerly occupied by a conveyer-belt sushi restaurant.

Amazon Books is presumably intended as a showroom for Amazon.com, a physical manifestation of everything Amazon’s founders believe, and a destination for Amazon’s most enthusiastic fans. If corporations can feel pride — and why not? they’re people, after all — Amazon Books thrums with a glowing sense of corporate self-regard. This is a brand that is singing a song of itself.

Every inch of Amazon Books is a promotion for Amazon.com, a meatspace billboard for a virtual experience. The speakers play inoffensive jazz that signs helpfully inform you can be found on Amazon Prime Music. Books are priced, other signs crow, the same as they are on Amazon.com. The center row of the store is handed over to Amazon’s physical products — the cylindrical, always-listening Echo; the colorful Fire tablets for children; the generic Bluetooth speakers; the television streaming boxes. But aside from a tablet here or there, the rest of the store is devoted to books. The vast majority of the books are faced-out on shelves, with a few endcap displays and a couple front table of new releases.

Spend five minutes in Amazon Books and you will likely describe it as a fairly typical corporate bookstore experience, a cleaner and more enthusiastic Barnes & Noble. But spend a little more time in Amazon Books — an hour say, on a Saturday morning — and you’ll realize the true achievement of what Amazon has done. All that data, all those national GDPs worth of products shipped, all of that has built to this moment, this destination, this apex. What Amazon has built in Amazon Books is nothing less than the world’s greatest airport bookstore.

Let’s talk about what bookstores do. Before I became a book reviewer, I spent more than a decade working in bookstores: at Elliott Bay Book Company, and at Borders, and briefly at the Brattle Bookshop in Boston. And part of the reason why the transition from bookseller to book reviewer was so easy for me is that they are, at root, the same job.

A bookseller’s job, and a book critic’s job, is to introduce books to the universe, to start the conversation between book and reader. If you think of a book as a concentrated chunk of thought and empathy and human experience, it’s in bookstores and in book reviews when they start to effervesce, and fizz, and the ideas start to spread into the atmosphere, where we breathe them in. It’s a bookseller’s job to make sure that the right book gets to the right person at the right time.

Sometimes, a bookseller will slyly sneak a subversive young adult novel into the hands of a teenager right in front of their parents — the kind of book that will alter the course of a life, handed off in a seemingly banal retail transaction. I don’t need to tell you the power of books; they can rewire brains, drop whole memories and emotions into our life story that wouldn’t have existed otherwise, and they can, more than any other medium, get us inside the heads of other human beings. They make us less solitary creatures. Every bookstore, then, has tens of thousands of conversations inside of it, waiting to be unleashed into the world.

Those conversations are on the shelves at Amazon Books, too. You can find titles by Ben Marcus and Gwendolyn Brooks and David Foster Wallace and Marilynne Robinson there. Part of the reason Jeff Bezos decided to use books to launch his online retailer was the fact that books are remarkably sturdy units. Every copy of The Scarlet Letter in a single print run is exactly like every other copy. You don’t have to worry about different sizes that have to be returned and re-shipped after a customer tries them on. You don’t have to worry about a book going bad after it passes its expiration date. So a David Foster Wallace book you buy at Amazon Books is the exact same book you’d buy at University Book Store. These books have the same power as any other books in any other bookstore in all the world. The problem is the way Amazon Books directs the conversation around those books.

Everybody knows by now that ads and retail sites online are directed toward individuals. Your Amazon buyer history means that you have a different Amazon homepage than me, and your Facebook ads promote different products than mine. The great failing of Amazon Books is that it can’t reconfigure itself for every customer who walks through the door. You’re not welcomed with a different set of front tables than I am; it’s the same selection, with Scott Pilgrim and the new Donald Trump book, for everyone.

So since the current demands of time and space demand that Amazon can’t suit their bookstore to match the need of each individual customer, they had to compromise. Instead, they decided to please everyone. The way Amazon did this was through a method that an Amazon spokesperson infamously described as “data with heart.”

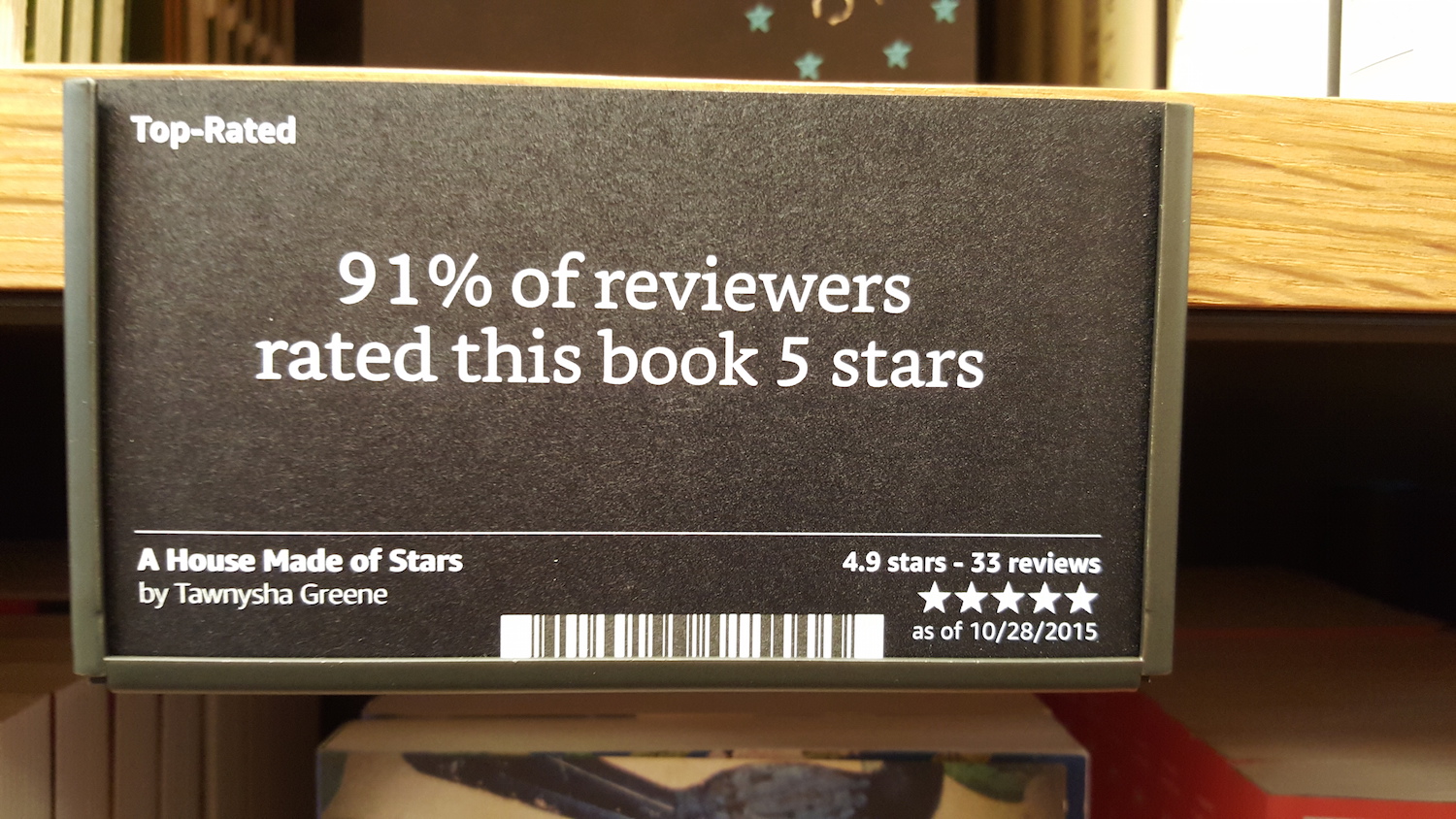

So what does “data with heart” mean, exactly? It means you get a bunch of awkward signs on endcaps promoting books with signs like this: “Highly Rated Business Books 4.7 Stars & Above.” Okay. That sure is specific. But what does that mean? How many people rated Paul Downs’s Boss Life 4.7 stars or above? Why did they rate it 4.7 stars or above? What would it mean if Boss Life was rated 4 stars? And how do books on that display compare to the books on the next display over, which a sign informs us is made up of “Business Top Sellers,” which are rated “4.5 Stars & Above?” Does that .2 star matter? Why or why not? What are you trying to tell us, besides the fact that these books are popular, and that people who rated them rated them highly? How does a 5-star rating for Getting to Yes relate to a 5-star rating for the Bible? You might give Purity 5 stars, and I might give The Complete Poems of Denise Levertov 5 stars. Maybe I’d give Purity 2 stars and you’d give Levertov 2 stars. Why, really, should anyone care? It's what you do with the book, what you learn from the book, and what you share from the book with the world that truly matters.

Supposedly, the aggregate is how Amazon defines the quality of a book. Many of us have gotten into fights on Facebook about a movie — Jurassic World, say. We know how those fights go. We’ve argued that the movie was dumb and bad but the other person replied, “well, it’s rated 92 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, so I guess someone must agree with me." As though an aggregate of critic scores is as immutable as, say, the speed of light, or freezing temperature, or the melting point of steel.

It’s just not that simple. If 500 people rate a book 5 stars and I read the book and hate it, that doesn’t make my opinion any less meaningful than theirs. It means I entered into a conversation with the art and I had a different conversation than those people. It doesn’t allow for the individual human experience, because it’s too busy condensing hundreds or thousands or dozens or however many experiences into five narrow lanes.

Imagine a restaurant that included Yelp reviews of specific dishes on its menu and you get an idea of Amazon Books. One recommendation card by an Amazon user named “scot16897” — there’s no sign whether Mr. 16897 consented to have his review printed, but that’s probably part of the boilerplate user agreement when you sign up for Amazon — praises a book by saying “Not only is the story good, but there are so many small jokes and references, I found myself literally stifling laughs while reading in public.” So, Mr. 16897, what makes a story “good?” Why is a story bad? What makes you laugh? Why should I suddenly care what an anonymous person on the internet has to say, just because his comment is printed on a card and slapped on a bookshelf?

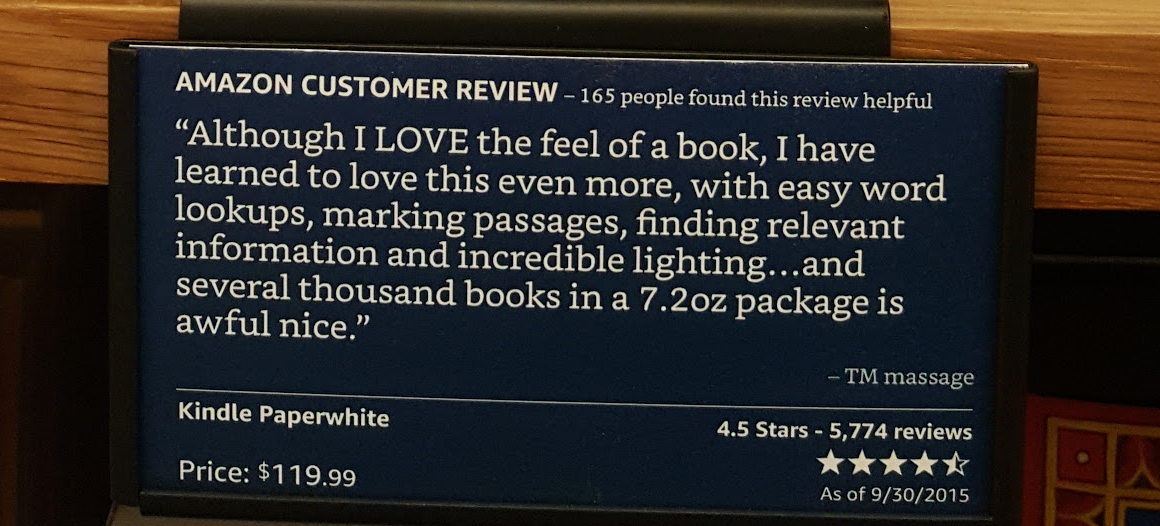

Most aisles of Amazon Books feature Kindles loaded with samples of the books on the shelves of that particular aisle. It’s a weird choice. Why would you push a bunch of buttons on a Kindle to summon up a sample of a book that already exists on a shelf right in front of you? Why wouldn’t you just pick up the book and start reading it?

The experience only served to remind me that e-readers now feel hopelessly outdated. I hadn’t held an e-reader in a long time, but the slow flashing of e-ink as I swirled through a menu felt like an old-timey experience. Even though the recommend card for the Kindle, written by one “TM massage,” assured me that they have “learned to love” the Kindle “even more” than “the feel of a book,” I felt like I was poking around on a manual typewriter. I say this as someone who bought an e-reader—a Sony Reader — years ago, when e-books seemed to be an inevitability. At the time, I thought reading on the device was fine, perfectly acceptable.

Now, even though the Kindle Paperwhite is supposedly Amazon’s top-of-the-line e-reader, it felt silly and awkward, a rickety reminder of a moment in 2007 when a man, high on internet hubris, actually believed he could render the book obsolete. I looked up from the soggy grey text of the Kindle, and blinked, and looked around at the bookstore, at all the kids poking at the tablets mounted in the childrens’ section, and thought to myself that everything eventually looks old and stupid and slow. Except books.

The final problem with Amazon Books is a curious one. Amazon.com made its name, in part, by having the biggest selection of books in the world. Their physical bookstore boasts a wide array of bestsellers, recent award-winners, and a few representative examples of classics. In comparison with the online retailer, Amazon Books is home to a remarkably shallow assortment. It’s like looking out at a lake that stretches almost to the horizon, stepping inside, and discovering that it’s a crystalline puddle, no more than a quarter-inch at its deepest part.

The poetry section of Amazon Books takes up a single bookcase. It has 26 titles in it, all faced out in even little stacks on four shelves. I left Amazon Books and walked a few miles to Third Place Books Ravenna, headed to the back of the store, and faced their poetry section, which took up two bookcases—15 shelves total. Every single one of those shelves had more titles on it than the entirety of Amazon Books’s poetry section.

I started counting. Third Place Books Ravenna had 758 poetry titles in its poetry section, the size of almost 30 Amazon Books poetry sections. Shelf tags in the section handwritten by store employees, people I could find and talk to in the store, directed me toward specific titles. A pair of display shelves faced out certain books that the employees liked. Nowhere did I see any statistics, or arbitrary 5-star ratings. It was a wall full of conversations, ready to launch out into the world. I breathed a sigh of relief. I was home.