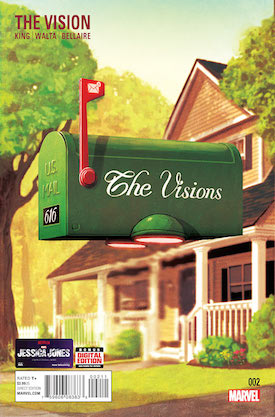

Thursday Comics Hangover: A vision of normalcy

Every once in a while, a truly individual voice will emerge out of the morass of conventional superhero comics. These occasions are always a surprise — nobody could have predicted that Swamp Thing would become a convergence point between art and commercial comics until Alan Moore and Steve Bissette landed on the book, and nobody expected much of Daredevil until Frank Miller was allowed to get experimental with the character. It’s too early to draw a comparison Tom King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta’s The Vision to those two examples, but two issues into the series, it’s already clear that the book is something special.

In the first issue, Virginia made a choice to protect her children, and in the second issue she constructs an elaborate fiction to hide the truth of what happened from Vision. The pair sit awkwardly on a couch, dressed like preppy humans in a clothing catalog, and they begin to understand the complexity of married life. “They could hear the stutter and roll of a skateboard riding through their street,” the captions explain….

…the lazy caw of birds yelling in the wind. The bland, passive roar of a 757 cutting into a cloud. These are the noises of their every day, the banal background to their new home. They used to sound so pleasant.

The Vision drops a godlike, aloof figure into the American suburbs of John Cheever, but it’s not interested in easy satire. Instead, it deals with the discomfort of what happens when you finally get everything you ever wanted, and the vertiginous moment when you realize that life just keeps going after you achieve your dreams.

Gabriel Hernandez Walta’s art perfectly resonates with the hollow echo accentuated in King’s script. He’s not interested in making the Vision and his family look human, but they’re not superhero-idealized, either. Instead, they look like they’re trying to behave like humans. They move with a kind of uncomfortable emulation, except for the moments when they take to the skies. When they fly, they’re graceful and lean. It’s one of the few times they’re not trying to pass for normal.

We’re only on the second issue of The Vision, which means things could yet go totally wrong. But the first issue ended with one of the darkest twists I’ve read in a Marvel comic, and the second issue is cloaked in an appealing sense of impending doom. You get the sense as a reader that if King and Walta are allowed to make future issues of The Vision as uncomfortable and full of yearning and quiet moments as these first two issues, you could be watching the start of something truly memorable.