Thursday Comics Hangover: Norovirus vs. Mark Millar

Last week, I contracted norovirus. It was terrible, and I’m not going to tell you any more about it except to say that I wound up in bed for 36 hours, feeling awful. I couldn’t watch movies. I couldn’t read poetry or prose. All I could stand to read, all I could focus my attention on for more than a minute at a time, was comic books. This has pretty much always been true for me; whenever I come down with an illness bad enough to send me to bed, I wind up reading comics. I always have a little stash of unread comics lying around for that moment when I get sick and need to get out of my head.

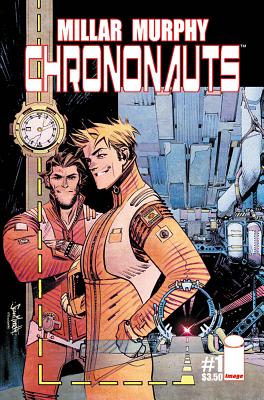

I had bought a used collected edition of Mark Millar’s and Sean Murphy’s comic Chrononauts at University Book Store and added it to my sick stash about a month before the norovirus kicked in. I’m a fan of Murphy’s art — the man can draw anything, from a futuristic pirate civilization in The Wake to religious parody in Punk Rock Jesus — but my feelings for Mark Millar are decidedly more complex. In fact, I think I hate him.

The sad truth about Mark Millar is that almost all of his comics could be pitched as “What if __ were irresponsible?” His comic Kick-Ass is about what would happen if superheroes were a bunch of irresponsible pricks. Civil War and Old Man Logan are about what would happen if every character in the Marvel universe started to act like an asshole. The Ultimates is about the Avengers being egomaniacal monsters. Jupiter’s Circle is about the Superman family of characters acting like the Kardashians. And on and on and on. Not that there’s necessarily anything wrong with this, in theory: virtually any premise could make a good comic, if handled correctly. But Millar’s characters are all the exact same asshole, the kind of insufferable douche who gets drunk at a party and immediately starts bragging about how awesome his life is. If Millar’s parodying something, that parody gets lost in all the obnoxious braggadocio.

Here is the plot: the time travelers decide to rule the world. “Back home I’ve got nothing, dude” the inventor of the world’s first time-travel device tells his friend. “Here, I’m a king,” he says, and he gestures around his kingdom: there’s a large print of a woman wearing a bikini on the wall, and a few sports cars, and a pool table, and some samurai swords. It’s a 15-year-old boy’s idea of what ruling the world would be like.

Again, maybe this is supposed to be satire. Maybe Millar intends Bill and Ted Meet Tucker Max to be commentary on the empty-headedness of modern men. But satire comes from a moral place, and there’s no real moral judgment at play here. In fact, this book seems to step back on every page and shake the reader by her shoulder and say, “isn’t this totally awesome?” It’s all a set-up for a cross-time chase sequence that lasts several issues and is impeccably illustrated by Murphy. But there are no stakes, no lessons, and no real surprises. It’s just exactly the kind of dick-swinging jackassery that a teenage boy would write, only drawn and packaged professionally.

Every time I read something written by Mark Millar, I feel unclean afterwards. He’s made his fortune by writing directly toward the ugly id of a very particular brand of comics fan, the self-entitled nerd-bros who dominated the industry for decades before women and minorities finally made their voice heard. Millar’s leering adolescent power fantasies feel like the deathbed rattle of an industry that refused change for as long as it possibly could.

Lying there in my sick bed, I couldn’t get Chrononauts out of my head. Those two terrible men who do whatever they want and avoid all repercussions took up residence there in bed with me, fist-pounding and trying to out-brag each other about how cool they are. Chrononauts left me feeling even sicker than I felt before I picked it up. It left me with the realization that even norovirus is preferable to Mark Millar.