Thursday Comics Hangover: Secret War is over (if you want it)

You can't really explain Secret Wars to someone who has no prior experience with Marvel Comics. Here's a rough attempt at describing the premise: Doctor Doom has willed himself to godhood, presiding over a patchwork planet constructed from dozens of alternate universes featuring Marvel's heroes in all sorts of strange combinations — cowboy Captain America, 1990s cartoon X-Men, Thor cops, and so on. On its face, it's just an excuse to dress up the old familiar superheroes in new costumes for a while. But in its execution, Secret Wars read like a Game of Thrones-style saga that investigated the very idea of superhero comics.

Hickman's script is dense and witty and, to someone who has never read a superhero comic before, likely impenetrable. But the impenetrability is a feature, not a bug. Just as TV shows like The Sopranos and Breaking Bad rewarded viewers who watched the whole series from beginning to end, all of Hickman's Marvel work since 2009 has proven itself to be a single text with a beginning, a middle, and a conclusive end.

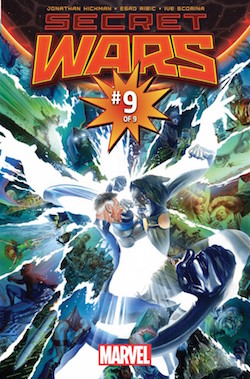

And so how is the end? It comes together better than I ever would have expected, building to a conclusion that is satisfing and relentlessly optimistic. What Hickman has built in Secret Wars #9 is a superhero comic about the joy and fun of superhero comics, a refutation of decades of relentlessly "realistic" (by which I mean depressing and dark) superhero comics. Rather than destroying legacies and killing characters, Hickman revels in the act of eternal creation. For the never-ending story that is monthly superhero comics, it's a fitting climax.

Ribic proved to be the perfect partner for Hickman's Marvel swan song. His heroes look heroic — even with his painterly style, grown men in spandex don't seem silly at all — and his rendering of Hickman's cosmic concepts feel at once alien and familiar. One page, featuring Mr. Fantastic and Doctor Doom's faces split into dozens of tiny panels and interspersed, mosaic-like, captures the theme of the series: over the course of decades, every superhero and super villain contains multitudes of interpretations and renderings. Those many selves, from the cartoonish 1960s to the realistic 1970s to the gritty 1980s, may seem contradictory and fractured, but if you stand far enough back and take the whole tableau in, you can see that the purity of the original concept still shines through. These are sturdy ideas, Hickman and Ribic are saying, and they will keep spinning out into the future in ways that will surprise us.