Thursday Comics Hangover: Sometimes no context is context enough

Recently, I visited a comic book store with a friend. She reads all kinds of graphic novels and collected comics, but she’d never spent more than a few minutes in a comic shop. Immediately, it became clear that for people who haven’t spent their whole lives in comic shops, there’s a bit of a learning curve to browsing. She picked up a comic and turned it over, looking for an explanatory blurb, like the one you find on collected comics. Of course, there are no blurbs on monthly comics. Aside from the cover image, there’s no indication at all what the comic is about.

Finally, frustrated, she asked me, “so how are you supposed to know what the comics are about?”

It was a great point. I explained that you could flip through the comic and see if you were interested, but mostly hardcore comic shop customers browse through a catalog months in advance, read promotional copy about upcoming comics, and order their comics based on that. It had never struck me exactly how weird this system is. Can you imagine what it would look like if bookstores — or, really, any other kind of art at all — relied on the same business model?

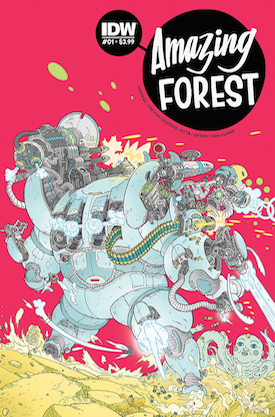

But that’s really all I know: are the stories supposed to be thematically linked? Two of them are weird science stories and two fall within disparate subgenres of fantasy. Reading Amazing Forest was a strangely unmooring experience, because I wasn’t sure if the stories were one-shots or the first installment in serial stories. (In retrospect, I’m pretty sure they’re all self-contained.) Only after I’d read the thing twice through did I begin to have a sense of what the comic was.

Amazing Forest is a Twilight Zone-style comic, which is to say each of the stories focuses on genre, and they generally feature a twist of some kind. Some of the stories are more engrossing than others. The first story, “Tank” — about a crew of men in a futuristic tank who have to battle victims of a plague who bear an eerie resemblance to long-lost loved ones — is good but a little too high-concept for eight pages. The twist in the second story, “Wolf Mother,” left me cold. “Ronnie the Robot” is an old-fashioned EC Comics-style riff, complete with a hoary climax that is pretty obvious, but which still feels satisfying. And the last story, “Bird Watcher,” ventures into weird literary fiction; a nuanced, creepy story, it’s by far the best of the bunch.

In the end, I don’t think I could really tell you what Amazing Forest is supposed to be. It’s kind of an anthology, except they’re all written by the same two people. It’s a short story collection, but the breadth and range of genres give the comic more of a wide-ranging feel and less of a thematic cohesion. That unmooring I mentioned before is not so much a bug as a feature; this is a book that benefits from your inability to categorize it.