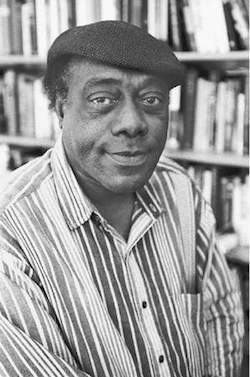

Remembering James Alan McPherson

James Alan McPherson, acclaimed American writer and writing educator, died last month, at the age of 72.

I studied with McPherson at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop from 1997 to '99. When we first met he hadn't published any fiction in two decades, but his kindness and his deep insights about writing drew me to his classes, and then to seek him out as a thesis advisor.

McPherson had been a correspondent for the Atlantic Magazine; in Ta-Nehisi Coates' 2014 piece "The Case for Reparations," Coates cites an Atlantic article McPherson wrote in 1974, a report on the Contract Buyers' League — an effort by a group of black homebuyers in Chicago to resist the predatory housing contracts forced on them by banks and abusive sellers. McPherson's great long 1969 article about Chicago gangs ("Chicago's Blackstone Raiders") is available on the magazine's website: for that piece, McPherson met with gang members and conducted interviews over a six-month period to create a picture of the entrenched and sometimes accidental ways in which gangs, public institutions, and churches simultaneously harmed and helped one another.

McPherson broke his two decades of publishing silence with a memoir called Crabcakes, which came out in hardcover during my first year studying with him. Now that he's passed, it has become his final book. Crabcakes is dense, wandering, floating between time periods, part history, part philosophy, part epistolary, part confession. I watched McPherson read from it to a packed auditorium at the Iowa Memorial Union in 1999, a stand-alone piece of formal satire titled "A Useful Demonstration of the Etiquette Necessary for Survival on the Secondary Roads Trailing Off the Busy Interstates During Times of Lapses in Essential Areas of Civil Responsibility, Late Summer, 1983." It's an ironically voiced recap of an interaction McPherson had with a police officer who'd pulled him over on a pretext only to discover that McPherson's registration was expired. The piece is a measured, faux-soporific "how-to" for any black man or woman hoping to survive an encounter with racist small-town law enforcement. When he read it, the audience really laughed. When I reread it this morning, I still laughed, but was struck primarily by the horror of the piece. It's as relevant now as it ever has been, in America. After the officer, with hateful language (which McPherson calls the "signal"), compels McPherson to exit his car:

Deporting, take care to not make any sudden movements toward either pockets or the interior of the vehicle. Most likely, it will be a personally interested official who will make this sort of signal. It should indicate that similar signals, drawn from the very same storehouse of vernacular expressions, are forthcoming ...

McPherson's character realizes that the challenge before him is to establish, in the mind of this officer, the existence of a common humanity between them. This lifesaving link is the key to survival, and not easily forged when a situation has begun as badly as racialized encounters with authority consistently do:

It is no longer a simple dispute between an official and an offender. It is now an exchange between the scant resources of the reptilian brain and its half-formed image of "other" which has, unfortunately, intruded upon, and blocked, its view of life in its traditional mode.

But this, the satiric voice opines, is no misfortune. Rather, it's an opportunity "for an essay at that Reconstruction which, sadly, nowadays, is so everywhere in such great need."

A big fan of Richard Pryor, McPherson once asked our workshop, "Who are the good comedians now, who tell it like it is, but are still funny?" Some people in the class had suggestions, but it was finally agreed that the world was forever poorer for the fact that it would never again have a Richard Pryor.

As with this man, my advisor, teacher, and a first-rate writer — the "great need" grows greater with each passing year, and for all the wonderful and gifted voices speaking to it, there will never be another like his.