Thursday Comics Hangover: They put a man on the moon

If you love books and you haven’t read cartoonist Tom Gauld’s terrific collection You’re All Just Jealous of My Jetpack, you’re missing out. The book is packed with clever riffs on genre and famous authors, demonstrating Gauld’s deep reading life and obvious wit. He’s one of us, it announced to book nerds, and he’s not afraid to show it.

Gauld’s newest book, Mooncop, is totally different: it’s a single comics story, a(n admittedly slender) graphic novel that couldn’t be more rhythmically opposed to the compact gags of Jetpack. It’s the story of a police officer on the moon, years after a lunar colony’s glory days. Gauld takes his time with the story, eschewing the quick gags of Jetpack to draw many swaths of large silent panels to set the desolate scene. The humor in Mooncop is quieter, sadder, more humane.

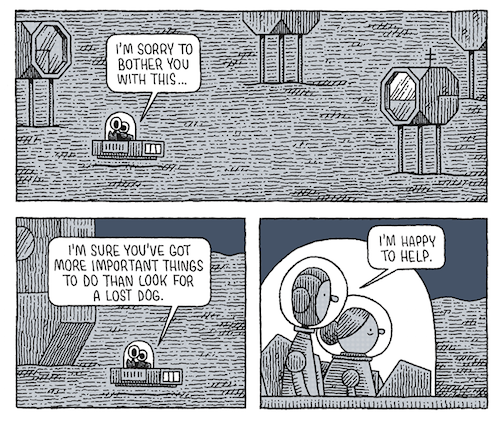

And as a cartoonist, Gauld has never been stronger. The figures in Mooncop are still cartoony, with simplistic faces behind circular astronaut helmets and pipe-cleaner-bendy limbs. But the detail he packs into each panel is gorgeous: the empty landscape of the moon is made up of thousands of tiny wiggly lines, a sea of stone set against an indigo sky.

The title character in Mooncop, who for the sake of expediency I’ll just call Mooncop, is a hapless fellow, a lonely man who’s left to police the dwindling lunar population. Just about everyone else has moved back to earth. “Living on the moon,” an elderly woman muses to Mooncop, “Whatever were we thinking? It seems rather silly now.” Once the allure of the frontier has dissipated, it seems, the bulky helmets and space suits required to live on the moon aren’t worth all the trouble. But some people still fall for the romance of it all: Mooncop replies, “Not to me. I think what you did was wonderful.”

Mooncop rides around the lunar colony, helping people as best he can and cleaning up after the remains of the adventurous spirit that brought humanity to the moon. Even a museum tracking the history of space travel is moving back to earth because nobody on the moon cares anymore. Gauld does include a few great jokes, particularly involving a robot therapist that is woefully unequipped for its job, but they’re unhurried. He has the patience to allow them to show up when they’re good and ready.

It must be said that the last few pages of Mooncop seem telegraphed well in advance; anyone who’s read a melancholy comic or two will be able to predict where Gauld is going to end his story once the necessary elements are introduced to the narrative. But this isn’t a book that you read for a twist ending or a roller-coaster plot. It’s more of a character sketch, a tone poem.

Between Brexit and the rise of Trump, this is a very appropriate year for Mooncop. When faced with the future, whole populations are recoiling. That one small step for mankind seems to have been a step too far; we’d rather be down on earth, soaking in our familiar humid air, than experiencing new things or trying to embrace the future. It feels lonely out on the frontier these days.