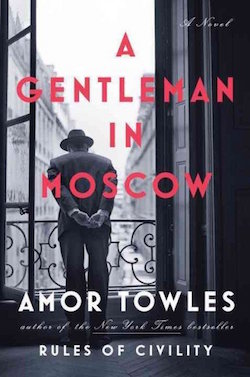

Literary Event of the Week: Amor Towles at FOLIO

The Count is a wondrous literary creation. He’s dignified and intelligent, but also weirdly displaced and kind of petulant. As a reader, you don’t know whether you should respond with disgust at the fact that he’s so unprepared for the roughness of the real world or with appreciation at the fact that his coping mechanism—pretending that the Revolution merely left him temporarily indisposed—is so marvelously effective. This is a character who is at once plain-faced and complex, the kind of rare protagonist who’ll live in your head for years.

Comparisons between novels and films are often misleading and unfair to both ends of the simile, but I can’t be the only reader for whom the opening pages of Moscow bring Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel to mind. Like the film, the book is densely populated with a broad and mildly cartoonish cast of characters, it’s set in a beautiful and sprawling hotel, and it’s enlivened with a broad and gracious variety of wit.

But that comparison between Moscow and Budapest is perhaps a feint masking an even more apt relationship: Anderson himself was very open about his film’s relationship to the works of Stefan Zweig, an Austrian novelist from the early half of the 20th century who went largely unappreciated while he was alive. And in fact Towles’s book is even more worthy of the claim to Zweig’s legacy than Budapest was: both Towles and Zweig write deceptively light prose that enchants a reader, and both writers use their chipper cleverness to disguise a considerable darkness underneath.

Whereas Zweig’s fiction always recoiled from the Nazi occupation that forced him to flee his home in the late 1930s, Moscow follows 30 years of Russian history from the Revolution to the dawning of the Cold War, all from within the walls of the Metropol. Some of the most brutal moments of the 20th century unfurl before the eyes of an inscrutable protagonist who tends toward heroic displays of understatement: “Let us concede that the early thirties in Russia were unkind.” That’s certainly one way to refer to famine, riots, brutality, and the rise of Stalin.

There will undoubtedly be some readers who chafe at the idea of an entire book that witnesses nearly a third of a century’s worth of a nation suffering from a sheltered aristocrat’s perspective. They are perhaps missing the point: in the Count, Towles has created a marvelous stand-in for the resilient human spirit: even in rags and imprisonment, he bears himself with dignity. Even if just in his own mind, he is a Count.

(Amor Towles reads at FOLIO: The Seattle Athenaeum tonight at 7 pm. The reading is $5.)