Thursday Comics Hangover: The city gone by

When I was younger, I didn’t really understand the appeal of Ben Katchor’s strip Julius Knipl: Real Estate Photographer. It has always been easy to see that Katchor is a talented artist — every panel is a beautifully composed portrait of urban life, every person in each panel has their own unique personality and history. But something about the strip resisted my attentions. I couldn’t find a character to identify with in Knipl, or any situations that spoke to me. I chalked it up as one of those rare strips — Prince Valiant is another — that is clearly of high quality, but which never really grabbed my attention.

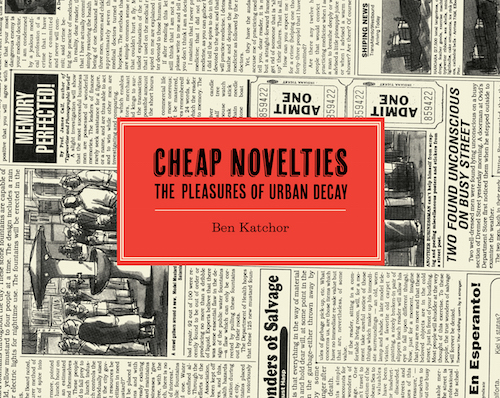

Drawn & Quarterly just reissued the first real Knipl graphic novel from Katchor. It’s titled Cheap Novelties, and it’s a beautiful book, designed to look like it’s been wrapped in old newsprint, with the strips reproduced in a larger-than-life format. I thought I’d give it another try, as I’d done on multiple occasions over the years, just to make sure Katchor’s work still didn’t work for me.

Every once in a while, a reading life suddenly shifts dramatically, and a once-impenetrable work of art instantly melds with your subconscious. That’s what reading Cheap Novelties was like for me. From the very first page, I immediately understood the point of the Knipl strip, and of Katchor’s work. I eagerly read Cheap Novelties and found myself wanting to reinvestigate all of Katchor’s books.

The thing I had never quite understood about Katchor’s strip is that the city is the main character. Every page in Cheap Novelties is about some strange aspect of city life: a failing chain of flophouses, the diminished prominence of kosher slaughterhouses, the variety of paperweights used to hold down newspapers at newsstands. They’re little tributes to disappearing aspects of city life, some real and some fictional.

Katchor works at the boundaries of nostalgia and the black hole of memory created when something disappears from our shared experience. I’ve heard plenty of people reminisce fondly about the simple and immobile analog pleasure of landlines, for example, but very few people can remember the satisfying heft of carrying a desktop phone in their hands, or the weird, voyeuristic frustration of sharing a party line with their talkative neighbors. You don’t long for the disappearing city that Katchor documents in Cheap Novelties, exactly, but you do want to acknowledge it, to pay it tribute somehow by bearing witness.

In one strip, a movie theater removes its large marquee and replaces it with a smaller, more stylish sign, we are informed, “in an effort to look modern,” and “to save on electricity,” and “to be taken seriously,” and “to be tasteful,” and “to improve the block.” Our hero, eager to watch a film, walks right by the marquee-less movie theater without noticing it. “I thought it was around here…must be farther,” he mutters to himself. “Maybe those lights in the distance.” The name of the theater (The Bosporus) and the film (An Autopsy for Two) are just extra punchlines on top of the poignant vignette.

Cheap Novelties doesn’t aspire to make cities great again, and it’s not interested in wallowing in the past, or whitewashing history into something wholly admirable. But in every strip, Katchor is throwing a wake for some quotidian urban object or another, admiring them for the purpose that they served, even as he acknowledges that the world has moved on. If you’ve never appreciated the appeal of Katchor’s work, I urge you to give Cheap Novelties a try. Katchor admires and celebrates a city that has suddenly become irrelevant, and his work has a way of suddenly finding a new relevance when you’re ready to see it.