Thank you for coming to the first Reading Through It book club

Nearly a hundred people came out to Third Place Books Seward Park to discuss J.D. Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy for the first Reading Through It book club last night, and most everyone who spoke seemed to agree that the book was not, strictly speaking, good. Most of us found Vance to be an aggressively un-introspective narrator, and many of the speakers expressed frustration at the way he glossed over what seemed to be the book’s major points.

That’s okay; not every book needs to be good. But I firmly believe that every book — no matter how flawed — does contain some sort of value. And in fact, sometimes our job as readers is to find the value of a book even when the author makes that value difficult to find. That’s where book clubs are especially helpful.

The idea for Reading Through It came wholly from Seattle Weekly’s editor-in-chief Mark Baumgarten, and he joined me onstage with Seattle Review of Books cofounder Martin McClellan to help moderate the discussion. I agree almost completely with McClellan’s review of Hillbilly Elegy; I found it to be an arrogant book, and I thought Vance’s conservatism caused several serious contradictions in the narrative’s internal logic. Vance seems to believe in the concept of systemic poverty, unless it interferes with his own bootstraps self-mythologizing. He divides poor people into “good” and “bad” categories, and he doesn’t make a compelling case for that black-and-white separation. Baumgarten also had issues with the book, but he took a slightly different approach than our straightforward critical appraisal, aiming to discover the objective truth hidden behind Vance’s narrative.

But the people onstage weren’t the important part. In an hour and fifteen minutes, the audience comments covered a lot of ground. Some took issue with Vance’s politics. Others brought their own experiences with impoverished communities — in America and around the world — to the book, and compared what they found. Some made the distinction that white people are not from one homogenous background — that the long history of intergenerational trauma behind Vance’s Scots-Irish heritage contributed to his family’s poverty just as much as their geographic location.

Many of the speakers called for us to keep multiple perspectives in mind at once. It’s possible, for instance, to simultaneously experience white privilege and to experience tremendous obstacles due to class distinctions. Issues of class and race and geographic disparities aren’t an either-or proposition; they tend to overlap and undermine and interact with each other in strange ways.

People tried to offer solutions for the poverty they read about in Hillbilly Elegy. One reader suggested the need for programs to bring urban citizens to rural communities. Several people discussed the importance of education, and particularly the importance of empathy in education. The unfortunate fact of entire populations relying on one economic engine for its survival — a factory, say, which could close or move or automate — came up again and again.

And a few people delivered cogent critiques of the narrative. One person read a passage in which Vance, as a Marine in Iraq, encountered a child living in unspeakable poverty. He was frustrated by Vance’s inability to recognize his own experience in that child; instead, Vance used the moment to celebrate the fact that he grew up in “the greatest country in the history of the world.” Others pointed out Vance’s eagerness to create distinctions — between proud poor people and what he considered to be shameful poor people, between white poverty and poverty experience by other races.

But other people dissented from the room’s distaste for Vance’s story. One speaker saw a sarcasm, a sense of humor, that she felt everyone else was missing. Another speaker thought Vance was an eloquent observer of human behavior who reflected her own lived experience. The way they read the book, and brought their unique readings of the text to the rest of the book club, added value to the book that many of us in the room had never before observed. In other words, they opened our mind to another perspective, which is exactly the point of getting together in a book club.

The room voted to make Rebecca Solnit’s meditation on the value of hope in dark times, Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities, our February discussion topic.

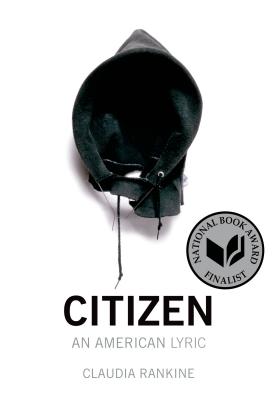

Folks hung around to talk about Hillbilly Elegy in small groups. Some of them headed downstairs to the bar to drink and get into it with friends. Others picked up Citizen and a few other books on the way out. “At times like this, reading feels like the most important thing you can do,” someone told me by the registers. I completely agreed.

If you'd like to continue the discussion about the book or make a point that you didn't get to share last night, feel free to join us in the Facebook thread for this post. And please join us on January 5th for more meaningful conversation with a room full of smart people who care.