Literary Event of the Week: Come discuss Citizen: An American Lyric with us tonight

Last month’s Reading Through It Book Club was a great success, a night in which nearly a hundred Seattleites gathered to discuss an America that they felt they didn’t recognize anymore. The event — a coproduction between the Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Review of Books, and Third Place Books Seward Park — didn’t provide a whole lot of answers, but it did evoke important questions of class and race and intergenerational poverty. People shared their own experiences with poverty, both from personal experience and as observers. They talked about their personal biases and how those biases might have failed them. They told jokes. They focused their view of the world through the lens of a book.

This Wednesday, I’ll be joining with Seattle Weekly editor-in-chief Mark Baumgarten and Seattle Review of Books co-founder Martin McClellan for the second Reading Through It at Third Place in Seward Park, and there will be so much to discuss.

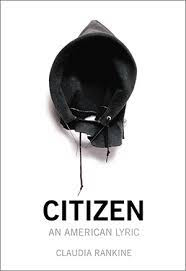

Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen: An American Lyric first caught America’s attention when a young African-American women named Johari Osayi Idusuyi read it at a Trump rally in late 2015. Idusuyi, who was seated directly behind Trump in a video feed of the rally, pulled out Citizen and started reading it after she realized exactly the kind of event she had attended. (She told an interviewer at Jezebel that she went to the rally with “genuine intentions” to see if Trump would talk about “something of substance.” All of America would feel Idusuyi’s disappointment just one year later.) An old white couple took great offense at her literacy, and tried to get her to put the book down. She politely refused.

That whole exchange is remarkable because it’s exactly the kind of scene that would fit into the opening of Citizen. Rankine begins the book with a series of short paragraphs written in the second person detailing the many small frustrations and outrages black people experience in America today. These are not the cross-burning behaviors that come to mind when we hear about racism, but rather an array of microaggressions, thoughtlessness, and the learned normalization of whiteness.

Consider this tiny fragment of a sentence: “…he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there.” It’s a small thing, but the idea it presents is so huge: through inarticulateness or ignorance or outright aggression, he’s stating that only white writers can be great, that writers of color can never be great. Perhaps someone out there — probably a white person — thinks this is inconsequential, that it’s a minor point. But Rankine continues to add up examples like this: the way Serena Williams is treated as a black tennis player, a white man shouting the n-word in a Starbucks who gets mad when people are offended by him. It looks less like a series of accidents and more like what it is: a system.

Citizen is a book that demands conversation. This is a time that demands thoughtfulness. I hope you’ll join us tonight for a thoughtful conversation about a remarkable book.