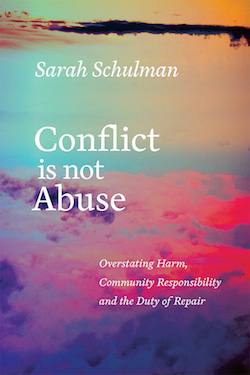

Literary Event of the Week: Sarah Schulman with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore at Seattle Public Library

“Provocative” has become a dirty word. As Donald Trump lurches toward the presidency and white nationalist Milo Yiannopoulos scores a $250,000 book deal, provocation has become synonymous with trolling, and trolling has gone mainstream. When Seattle authors Lindy West and Sherman Alexie very visibly quit Twitter last week, they demonstrated an exhaustion with provocation. We’ve had it with devil’s advocates and thought experiments that are intended to do nothing but get a reaction out of us.

Which is not to say that Conflict won’t piss you off. You likely won’t agree with all Schulman’s arguments, but that’s kind of the point. “This is not a book to be agreed with,” she writes…

…an exhibition of evidence or display of proof. It is instead designed for engaged and dynamic interactive collective thinking where some ideas will resonate, others will be rejected, and still others will provoke the readers to produce new knowledge themselves.

Her thesis in Conflict is to deflate the concept that feelings are inviolable, that, as the dust jacket suggests, too often in the 21st century, “inflated accusations of harm are used to avoid accountability.”

This is tricky stuff. Plenty of boring middle-aged white dudes have clambered up on social media platforms to sound the alarm about trigger warnings and “PC culture run amok.” Those rants aren’t worth your time; they’re the bleats of the cowardly and the closed-minded. Schulman approaches some of the same topics from a different place: “I ground my perspective in the queer,” she writes. “I use queer examples, I cite queer authors, I am rooted in queer points of view…I come directly from a specifically lesbian historical analysis of power.” Later, she notes that she “grew up in feminism.”

Schulman’s arguments are based largely in anecdotes, a method that is at once illuminating and frustrating. Her suggestion that a terse and stressful email exchange passive-aggressively stretched out over days could have been resolved by a five-minute mildly confrontational phone call is a good one. But Schulman’s story about directly engaging with a student who pursued her with behavior that could be interpreted as stalking is much less convincing; it’s out on these extremes when the theory starts to creak and groan.

Schulman’s claim that we should face the unpleasantness of conflict rather than conceal ourselves in bubbles of agreement doesn’t effectively address the 21st century’s most nonrenewable resource: attention. A human being simply doesn’t have time to engage in conflict with every available opposing viewpoint; a moral citizen of the internet has to choose her battles, and that act of selection can create its own conflicts. At some point, as West and Alexie’s exodus from Twitter proves, conflict for conflict’s sake is simply not worth it.

(Sarah Schulman reads at the Seattle Public Library with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore on Tuesday, January 17th at 7 pm. The reading is free.)