The Future Alternative Past: this dystopian hope

Unreality show

Interviewers sometimes ask me which mode of science fiction is easier to write: Utopia or dystopia? Look around you, I answer. Dystopian fiction is basically mimetic (realistic) fiction. It’s way, way too sodding easy to depict a scenario so ubiquitous; I choose to get my jollies envisioning the Utopian coolness that could be.

Equality and perfection are two hallmarks of Utopias. Especially for members of non-dominant groups like myself — women, queers, racial minorities, etc. — the status quo has long been anything but egalitarian, and its operating methods far from perfection. Even able, cis, white, heterosexual, young, middle class males are having hard times lately, though. Or so I hear from friends who fit those default categories.

We haven’t always inhabited this particular nightmare, and for decades science fiction/fantasy/horror has produced cautionary tales which could have warned us away from it. Thus my unease at the rise of “reality shows,” those television programs, common since the beginning of the millennium, in which supposedly unscripted action features non-actor celebrities and unknowns. I first encountered mention of them in extrapolated futures I wanted no part of, like James Tiptree, Jr.’s short story “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” and “Baby You Were Great” and “Ladies and Gentlemen, This Is Your Crisis,” both by Kate Wilhelm. Novels from William Gibson, Barry Malzberg, and John Brunner fleshed out the picture: corporate ownership of governments; 24/7 surveillance; a culture of jaded, passive cynics.

Now a reality show star has been elected President of the United States. Now I’m living in the sort of world I didn’t even like reading about. Now I want to know how to change life’s channel.

So of course, being me, I turn to the imaginary.

Of published work, the most optimistic science fiction/fantasy/horror written recently on the topic of elections is Malka Older’s Infomocracy, a June 2016 publication that leaps a couple of decades ahead to a time when “microdemocracies” — non-geographical communities of 100,000 citizens — cover the globe. While Older’s depiction of how such a system would work — and fail — if put in place is entertaining in a governance geek way, this novel gives no turn-by-turn guidance on getting where it shows us winding up.

More promising in terms of finding a way forward, perhaps, are a pair of projects only lately underway. Ben Winters, Philip K. Dick and Edgar award-winning author of Underground Airlines, is putting together a series of stories “contemplating the future of our nation and world during and after a Trump presidency.” Scheduled to start appearing in Slate Magazine on Inauguration Day, these stories will be set in the 2016 presidential election’s immediate aftermath. Judging by the list of authors participating, bitterness, irony, and parody will probably be mixed with inventive strategies of resistance.

One prominent name on the list is crime fiction writer Gary Phillips, who will also edit The Obama Inheritance, an anthology in which contributors “riff on any one of dozens of teabagger-alt right conspiracy theories.” Time-traveling John Birchish saboteurs intent on destroying the president’s birth certificate, Michele wielding Pam Grier-worthy kung fu skills, and scenarios even more psychedelic than these seed the book’s proposal. In audacity there is hope.

Couple of upcoming cons

Held February 3-5, Foolscap is a small, local convention that wants you to decide what it will consist of. Members plan the weekend’s programming at a Friday afternoon meeting, scheduling panels and discussions around set pieces such as an auction, a banquet, and writing workshops. Their first Guest of Honor was Octavia E. Butler, and 2017’s is Patricia Briggs, but this con’s website claims that “Everyone is interesting.” Come take advantage of this least hierarchical of fandom’s famously non-hierarchical communities. And bring your brain; quoting again from Foolscap’s website, “Ideas make the best toys.”

Radcon is a more conventional convention, so to speak. It features the usual panels, gaming rooms, film viewings, and masquerades. Idiosyncratic strengths include well-organized school visitation sessions for professional writers; a chill, rambly hallway scene with an upright piano providing mood music; and a rave-like dance party.

Recent books recently read

If SFFH’s Golden Age is 12, as some insist, the genre’s Golden Format is the short story. Just the right size for having adventures in, short stories allow authors and readers to experiment with settings, ideas, characters, styles, so forth, so on, without making us invest huge wads of wordage. And anthologies with unifying themes both inspire these experiments and bring them together, thus making it easy to compare the ways they work.

The editor of Latin@ Rising (Wings Press), Matthew David Goodwin,focuses on SFFH by US-connected Latinos/Latinas/Latinx writers. The closest comparable anthology is 2012’s Three Messages and a Warning, a book of new SFFH by modern Mexican authors. Though over a third of Goodwin’s selections are reprints, they’re of recent enough vintage that this book feels fresh and damp, as if the ink hadn’t yet made up its mind to dry. In particular I enjoyed the Klein bottlesque plot curvature of Kathleen Alcalá’s “The Road to Nyer” and Ernest Hogan’s far-too-relevant politipunk story “Flying under the Texas Radar with Paco and Los Freetails.”

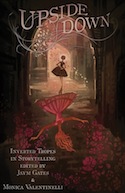

Paying less attention to source than content, Jaym Gates and Monica Valentinelli, co-editors of Upside Down (Apex), asked contributors to invert “tropes,” worn storytelling clichés such as “The black man dies first” (full disclosure: I have a story in this book based on that very cliché). Their directive results in surrealistic premises such as the trendy small-appliance bodymodding in Adam-Troy Castro’s “The Refrigerator in the Girlfriend.” But it’s also interesting to see how some authors subvert their chosen tropes rather than simply standing them on their heads, as when in “Those Who Leave,” Michael Choi’s Asian scientist is emotionally driven rather than a stereotypical personification of cold, passionless intellect. Plenty of pleasure of all kinds here, including deeply moving weirdness from Michael Matheson and Haralambi Markov. A section of essays by academics and writing professionals on tropes in general and certain toxically tempting ones in particular adds further depth to this already thought-provoking anthology.

At the opposite end of the length spectrum from short stories lies the realm of the series — quartets, septologies, and the like. Charles Stross’s Merchant Prince series began, according to the late David Hartwell, as this notoriously “hard” SF-loving author’s attempt at writing fantasy. Sharing the multiverse premise and settings as well as several “worldwalking” characters with the Merchant Prince books, Empire Games (Tor) could be considered their seventh volume or, as it’s billed, the first of a related yet different series, the Paratime trilogy. Either way you read it, Stross’s latest will deliver vivid, unexpected, complicated fun.