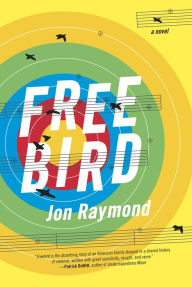

Literary Event of the Week: Jon Raymond reads Freebird at University Book Store

At some point, you have to figure, Jon Raymond will get sick of people comparing him to Raymond Carver. In reviews, the Portland-based author is said to “evoke” or hail “from the school of” Carver. Some reviewers even make the rare and fascinating observation that Raymond’s last name and Carver’s first name are — gasp — the EXACT SAME NAME. (Full disclosure, I very well may have made that Raymond-Carver comparison in past reviews; I’m too embarrassed to Google myself and find out.) If you work in the Northwest and you’re known for writing stories featuring short, declarative sentences and quiet epiphanies, it seems, you’ll eventually get branded with Carver’s legacy, even though it’s an obvious comparison, and one that does not withstand more than a few minutes’ examination.

If you’re reading his work through that particular lens, Raymond’s newest novel, Freebird, could be perceived as an almost-willful attempt to shake off the Carver mantle once and for all. But more likely, Raymond is just growing and changing as an artist. Freebird isn’t a book that belongs in the dusty, interior 1970s. It doesn’t reek of whiskey and regret. It feels, instead, like something new.

In fact, though Raymond has been crafting Freebird for years, it’s the rare work of fiction that feels more timely with each passing moment. It’s the story of the Singers, a California family that is constructed wholly from negative space. Grandson Aaron barely tries to bridge the chasm with his grandfather Sam, a Holocaust survivor. Anne, Aaron’s mother, is barely talking with her brother Ben, a Navy SEAL. And Anne, who works for the city of Los Angeles, is considering taking an unethical consulting deal on the side with a brown-water recycling firm — literally profiting from everyone else’s shit.

So Freebird is about the conversations we don’t have with each other — that we don’t want to have, because they’re too difficult. It’s about deciding to give up on basic human rules of conduct in exchange for a hefty profit. If you told me it was a book written for the fractured America of 2017, led as it is by a man who tosses civil behavior to the wind as he capitalizes on a fractured ideological landscape where Americans stay safely ensconced deep in their own viewpoints, I’d believe you.

The Singers are divided along political lines. There’s an age gap, and a cultural gap. History gets between everyone. And slowly everyone starts to wonder if maybe they’ve been wrong for many years. Here’s Ben, early in the book, considering the way he cheered for America’s wars:

Staring at his dad’s roof, imagining flames shooting skyward, napalm spreading over the earth, all manner of burning death, feeling his head slowly separating from his body, he began to wonder the once unthinkable: What if America was not imperiled by enemies on another continent at all? ….After almost three decades of extreme clarity on the matter, he was no longer at all sure. And without that clarity, there were other big questions to answer, too. Namely: If the enemy wasn’t out there, then what the fuck had all that violence even been for?

See what I mean? Raymond’s not some nostalgia act; he’s as vibrant as any author in the business today. Hell, it’s just like looking into a mirror.