Thursday Comics Hangover: The unhappiest children's books in the world

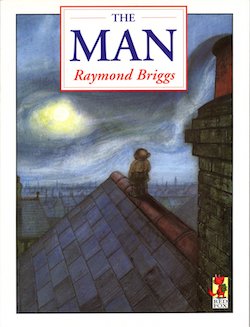

Like so many of the best books, I found it hidden behind a couple outdated computer programming manuals in a Goodwill. It’s a tall, slim hardcover book with a torn dustjacket. The cover is a soulful color sketch of a tiny figure standing on a roof staring out at a cloudy night sky. It says in big letters at the top, The Man, and below that, in smaller print, the author credit: Raymond Briggs.

You likely know Raymond Briggs for his wordless children’s book The Snowman, but Briggs has a long and colorful publishing history. He’s written and drawn dozens of books, and he’s been publishing from the 1960s to, most recently, 2015. Many of his books — including The Man — are out of print in the United States.

Because they deal almost exclusively in the interaction of words and pictures, most children’s literature is, in some form or another, comics. But Briggs’s work shares more of a common vocabulary with modern comics than most other authors for children. His books have multiple panels per page, and dialogue often depicted in word balloons, and the work features other comics traits that you don’t find in more “traditional” kid’s lit.

The Man, though, is a little bit of a departure for Briggs in format: the book features experimental layouts — often with one large illustration per page and dialogue typed out, in different fonts for each character, down the middle of the page. It’s less like a comic and more like a stage play. The book keeps its scope fairly intimate, too: it’s the story of a young boy who, one day, finds a bossy little naked man living in his room.

The man, who only answers to Man, demands that the boy fashion him some clothing out of an old sock and a rubber band, and then he proceeds to complain even more: “I wish you had real marmalade,” he whines when the boy smuggles some food up to him. When the boy wonders aloud if Man is a Borrower, he angrily spits, “Pah! Stories! I hate them.”

Man’s continual insistence quickly grates on the boy, and they begin to fight. “You exploit your smallness,” the boy yells at Man, “You know how to use it. You manipulate people by it. You manipulate me for your own selfish ends.” Man retorts, “You make out you are being kind, generous and caring when all you are doing is using my smallness for your own ENTERTAINMENT. You don’t care for me as a PERSON! To you, I’m just an entertaining NOVELTY!”

The Man’s tone is all over the place: it’s hilarious, and tense, and realistic, and more than a little upsetting. But it finally settles on a deep and melancholic sadness that speaks to the sacrifice we offer to others: even those we love most — those tiny people who show up naked and willful — can get on our very last nerves, and sometimes we lash out in uncomfortable ways. That’s a special kind of sorrow. The last page of The Man speaks to a sadness that I’ve never quite seen represented before in children’s fiction.

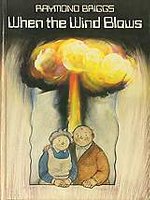

Briggs is no stranger to uncomfortable topics. Another of his out-of-print classics, When the Wind Blows, is, if anything, even more depressing than The Man. Wind is the story of an old British couple living in the countryside. They’re not especially deep or introspective people, but they’re law-abiding citizens who seem to enjoy each others’ company. One day, there’s an upsetting story in the news reports: nuclear war is breaking out.

A bomb drops not far from the couple, but far enough away that they’re not killed in the explosion. So they set about doing what any rule-following British citizens would do: they build a makeshift shelter in their home and they hunker down “for the 14 days of the National Emergency.”

Everything around them collapses — the radio stops working immediately and the nearby town’s supplies are wiped out soon after the first hit — but they continue living their lives: the wife wraps pillows in their shelter in plastic because “I don’t want finger marks getting all over them.”

Like The Man, Wind does not have a happy ending. Unlike The Man, Wind is well and truly apocalyptic. The couple start showing signs of radiation poisoning, but they still trust in the rules. “We’d better just lie here and wait for The Emergency Services to arrive,” the wife says. “Yes, they’ll take good care of us,” her husband replies as they huddle in potato sacks for warmth. “We won’t have to worry about a thing.” Those institutions will not save them. It’s dark. Really dark.

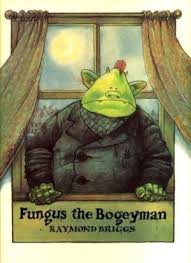

While not as bright as The Snowman, Briggs’s Fungus the Bogeyman is considerably lighter than either The Man or Wind. It’s the story of a bogeyman community that treasures the opposite of everything our society adores. Fungus’s wife wakes him at dusk on the first page of the book. “Time to get up, Fungus my dreary. It’s nearly dark.”

Fungus wakes up complaining: “OOOH! What a night that was! This bed has almost dried up!” His wife agrees, “I know, drear. It needs more slime.” Fungus walks over to a bin filled with cold water and pulls out his clothes for the day. A caption helpfully informs us, “Fungus inspects his trousers which have been marinading overnight." Fungus, his face inside a pair of pants, exclaims approvingly, “Mmmm! These really stink!”

Bogeyman follows Fungus through a typical day in his life. Throughout the book, captions explain Bogeyman culture, from the fact that they “cultivate boils on the back of the neck” to an account of the rotten grapefruit and “mouldy” cornflakes they eat for breakfast.

As an artist, Briggs is having a lot of fun here, experimenting with wild panel layouts and exaggerating the moribund dreariness of bogeydom culture. The expressionless dot eyes and upturned pig noses of his bogeymen give them a cartoonish appeal. It’s easy to imagine children falling into this book and being swept up in the many shades of sick-making green on every page, wondering at the intense oppositeness of Fungus’s world.

The best part of Bogeyman is how normal it all is. While Wind feels like a scathing refutation of humanity’s ability to remain docile in the face of global Armageddon, and while The Man revels in the way it upturns societal commitments, Bogeyman takes a sort of pleasure in the everyday rituals and cozy domesticity of its main characters. It’s unique in all of Briggs’s work in that it finds a sort of peace in its miserableness. It’s okay to be unhappy, Bogeyman says, as long as you’re okay with being unhappy — and don’t let anyone spread sunshine on your rained-out parade. It’s your party. You can cry if you want to.