Event of the Week: Lena Khalaf Tuffaha at Elliott Bay Book Company

It is probably no mistake that some of the best poets are translators. While translating poetry from one language into another is an impossible, thankless task — I’ve heard it described as performing open heart surgery with a chainsaw — it still teaches you to ask all the right questions.

Why did the poet use this word in that particular spot? Does a line break mean the same in this language as it does in the original language? Just because you’ve managed to assemble a word-for-word translation of a sentence, the rhythm of the translated sentence might be completely wrong — a sentence can sound like a crashing wave in one language and a galloping horse with a trick knee in another. Those airy, complicated questions of translation are bound to make anyone a better writer.

Redmond writer Lena Khalaf Tuffaha has translated other poets from Arabic to English. She’s written beautifully about the experience in an essay on her site titled “Translation as Poetry.” She explains that the “first time I unlocked one of these phrases on my own, I felt like I had put on goggles and was happily diving into the cerulean deep of a pool after years of blurry immersion.”

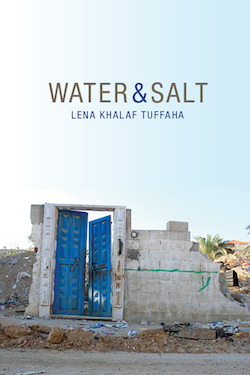

Now, Tuffaha is publishing her first book of poems with prestigious Pasadena publisher Red Hen Press. Water & Salt is a book that spans the globe, from Seattle to Jordan and back again:

We are driving away

because we can leave

on the magic carpet of our navy blue

US passports that carry us

to safety and no bomb drills

to the place where the planes are made

and the place where the president

will make the call to send the planes

into my storybook childhood

The repetition of the “planes,” there, from being manufactured to being launched, is a meaningful one. Here, in Seattle — once the Jet City, though that name has fallen into disfavor in the age of Amazon — the planes are a point of pride. They represent jobs and industry and security for families. There, they bring endings to childhood.

These poems bounce back and forth between worlds to look at familiar objects from both sides. Tuffaha compares vivid street markets to fluorescent supermarkets. She writes, “I love to tell you where I am from,” when she says “the nine letters” — Palestine, the “place with a name charged as an electric fence” — that inspire opinions in absolutely everyone. Her poems are addressed to ugly Americans and friends and Syrians and her close family. Even Tuffaha’s beloved coffee habit is different in America (“free-trade shade-grown organic”) than it is in the Middle East (“…never serve coffee without ground cardamom.”) The sun casts different shadows here and there. Everything looks a little different.

It becomes obvious as you read Water & Salt that Tuffaha is still deeply invested in the business of translation. Not even something as innocuous as an almond can just be itself. Here, they are dried and brown and vacuum sealed. There they are green and so sour they’re “puckering.” Her poetry is always translating something — experiences, cultures, memories — for someone else. She’s a patient intermediary, explaining how one word can have a million different meanings. It’s all a matter of perspective.