Future Alternative Past: hope for the ecospec-future

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Wednesday, May 3 — last night as I begin to write this — Annie Proulx gave a talk to the University of Washington’s librarians about global deforestation. It’s the topic of her most recent novel, Barkskins, a non-genre account of lumbering’s three hundred years of greed and waste. She knew whereof she spoke. But unlike fellow octogenarian Ursula K. Le Guin giving her famed National Book Award remarks, Proulx did not send chills up and down her audience’s spines. We had to listen carefully to hear her small, hesitant voice as she told us how she’d gathered beechnuts in the woods of New England as a child. “You can’t do that now. Those places are gone.” Difficult to digest that truth. Quietly, more unpalatable facts followed: the impact of hunting on carbon sequestering hardwoods, the reasons behind scientists’ agreement that we’re now living in a sad new Age called the Anthropocene, an era of high human impact on the biosphere.

Her topic’s emotional freight seemed almost too heavy for Proulx herself to carry: the speech ended abruptly, and I overheard her confessing to one of the inevitable cluster of admirers afterwards that she wished she could have continued. Maybe it really is too much for any individual to bear — the knowledge that we’re destroying our own habitat.

Pushing my way through the librarians and donors surrounding her — did I mention this event was a fundraiser? It was — I put in Proulx’s hand something she was in no position to offer me: hope. Specifically, I gave her a postcard for an anthology called Sunvault, a book of “solarpunk” stories postulating a future in which we overcome our species’ doom. Solarpunk, aka “ecospec,” aka “cli-fi,” is a subgenre of SFFH confronting the looming threats of melting ice caps, rapidly rising oceans, monster storms, and the thousand other slings and arrows of climatic catastrophe. Think Tobias Buckell’s Arctic Rising and Hurricane Fever, or more recently Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140, which I reviewed here briefly last month.

It’s not that the authors of ecospec deny climate change’s existence or impact (though I do know of one major SFFH publisher who enforces an outright ban on stories dealing with it). It’s just that that’s not where we stop. It’s where we begin.

Where do we go from there? How do we get to somewhere better? Depends on the writer. Fictional fixes applied to unsustainability can be technological or magical or political or any combination of the three; they can come from alternate timelines or aliens or marginalized humans, the forgotten past or the distant future. In addition to fixes there are adjustments: do we change our environment or change ourselves?

The answer, of course, is both. You get great ideas for doing the former and mental practice doing the latter when reading and writing cli-fi (or whatever else you want to call it; futurist Brenda Cooper, author of the forthcoming cli-fi novel Wilders loathes that particular term for what she writes). Proulx’s earliest published stories were SFFH. Maybe she’ll wend her way back to the genre and lay her burden down.

A few upcoming not-cons

Held annually here in Seattle, the Locus Awards Weekend isn’t exactly a con. There are panels, but usually no more than four. Readings, but only one. Parties, but just two. The main attraction is the Saturday afternoon lunch-cum-awards ceremony, emceed by the mighty Connie Willis with kibitzing from the indefatigable Nancy Kress. In honor of Locus magazine’s deceased founder Charles N. Brown’s sartorial preferences, Hawai’ian shirts are de rigueur — the gaudier and less authentically Hawai’ian the better. And though Locus is a serious publication (it’s basically the trade organ for English language SFFH), and the Locus Awards are serious awards, the ceremony itself is rather silly, with attendees vying for plastic bananas and novelty-store fake-grass Hula skirts.

Another not-con, NubiaOne Fest, will take place at a library in Auburn, Georgia over the evening June 16 and the afternoon of June 17. Figuring aficionados of Afrodiasporic SFFH would need something to tide us over between State of Black Science Fiction 2016 and SoBSF 2018, Milton Davis and Balogun Ojetade pulled together a sampling of their larger events’ programming, with participation from visual artist John Jennings, fellow authors Valjeanne Jeffers and Jeff Carroll, and others.

Now in its third year, The Brass Screw Confederacy proudly proclaims on its website that it “ain’t no Con.” A steampunk performance festival seems more like the proper description. Taking advantage of Port Townsend’s Victorian seaport architecture, costumed participants attend period-appropriate self-defense classes, play Tactical Croquet, and enjoy specially staged musical acts such as Frenchy and the Punk.

Recent books recently read

At least as prestigious as the Locus Awards, the Science Fiction Writers of America’s Nebula Awards will be presented May 19. Full disclosure ‐ my debut novel Everfair is on the final ballot. (AAAAAAA!!!!!) So with much personal interest I read the anthology commemorating last year’s contenders, Nebula Awards Showcase 2017 (Pyr). The field is overflowing these days with year’s best anthologies whose contents are chosen by experienced and renowned short fiction editors, but this is the only selection mandated by an entire organization’s membership. Surprisingly, the results don’t bite.

It’s an honor just to be nominated, and in addition to the winning short story, five other finalists in that category appear in their entirety. This is a boon to those of us who haven’t managed to hunt them all down. Here we have a chance to catch up on what professional SFFH authors believe is the genre’s forefront.

But this book’s pages aren’t infinite. Poems and longer works are represented only by their categories’ winners (poems, novelettes, and novellas) or by excerpts (novels). In the case of the new Damon Knight Grand Master C.J.Cherryh, who has written over 60 novels, we must content ourselves with excerpts from only two. Which could be sad-making. But add essays on other recipients and lists of honorees since the Nebula Award’s inception in 1965, and you have a complete yet handy-sized cross-section of SFFH’s most recent fruitings.

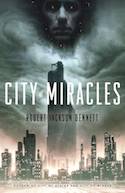

City of Miracles (Broadway Books) concludes multiple award-winner Robert Jackson Bennett’s Divine Cities trilogy. The series starts with the premise of magic as a tool of oppression: generations after the powerful gods which white, slave-owning “Continentals” worship get gunned down by a brown-skinned revolutionary, the pantheon’s occult legacies and byblows still cause the rebels’ new government trouble. Returning to Bulikov, setting of the first book, City of Stairs, Bennett leads readers through an astounding landscape: war-ravaged, partially restored, and lurching unsteadily into the future. Former enforcer Sigrud je Harkvaldsson deserts the seclusion of this fantasy world’s northern forests to investigate the assassination of his only friend, Minister Ashara Komayd. Is there Divine involvement? The presence of a toxic pocket universe say yes. Harkvaldsson survives entry and exit unfazed. He goes on to face down intimate truths and torturers with grim, love-steeped dedication; his painful eventual triumph is depicted with wit, restraint, and all Bennett’s artless-seeming art.