Thursday Comics Hangover: True colors

The future of comic books is not superheroes; it’s young adult fiction. If you look back on the last fifteen years or so of popular comics bestsellers, it’s pretty easy to track the direction of reader and creator interest, from Mark Millar to Bryan Lee O’Malley to Faith Erin Hicks. It’s not as big a shift as, say, the death of the western novel, but it’s definitely there: whereas comics used to be serialized monthly to large and eager audiences, we’re seeing more and more trilogies starring young characters (mostly girls) released in large chunks once a year or so.

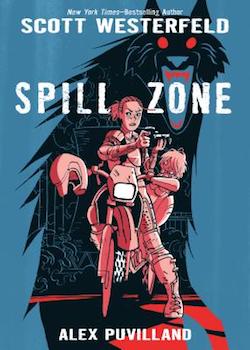

The latest example of the YA push in comics is Spill Zone, a sci-fi adventure comic written by Scott Westerfeld and illustrated by Alex Puvilland. Westerfeld, a bestselling YA novelist, has clearly done a lot of thinking about how to tell a story with comics: the world-building in Spill Zone is elegant without being overly expository.

Recently, an accident tore a hole in reality in the middle of a town in upstate New York. The authorities did all the usual things they do in case of a disaster: call in the military, cordon off the affected area, and keep the looky-loos away. But while the disaster isn’t spreading, it’s not going away, either. An aura of normalcy has crept back in to the situation.

Meanwhile, a young woman named Addie has been going on excursions into what’s now called the Spill Zone. As imaginative as Westerfeld’s descriptions of the Spill Zone might have been, credit must go to Puvilland for bringing those descriptions to the page: this is not your standard “weird” comics land, where all the monsters are brown and lasers fly around in the background. The Spill Zone feels like a land where anything is possible: step in the wrong place and you become 2D. Turn the wrong corner and an abstract expressionist wolf might eat you. Get too close to the mandala constructed out of floating bowling pins and ... well, who knows what’ll happen?

But a great deal of the credit for Spill Zone’s eeriness must go to colorist Hilary Sycamore, who renders the otherworldly neighborhood in flat, ugly colors that would not seem out of place in a 1970s kitchen. These olives and burnt umbers and swirling urine-yellow tendrils make it so a reader can flip through the book and tell with just a glance which parts of the story take place in the real world and which happen in the Spill Zone. It’s not a flashy coloring choice — one blanches to think what an early-2000s colorist drunk on computer effects might have done — but it’s brilliant. The comics business is full of great colorists right now, but Sycamore has to be one of the best.

Of course, since the next volume in Addie’s story won’t be published until next year, it’s impossible to determine whether Spill Zone is the great start of a great story or the promising opening chapter of a dud. But in terms of sheer world-building bravado and technical prowess, this book is worth your attention, as full of energy and imagination and enthusiasm for the comics form as any superhero comic I’ve read in the last few years.