"I didn't set out to do it, but what I had done was I made a comic": Talking with MK Czerwiec, cofounder of the Comics and Medicine Conference

This weekend, the eighth annual Comics & Medicine Conference will take place in Seattle. Registration is full, but the conference also hosts a number of programs at the downtown branch of the Seattle Public Library that are free and open to the public. The conference is bringing local and international cartoonists together to discuss the many ways that narrative comics about medicine can inform, entertain, and inspire the general public. Last week, I talked on the phone with MK Czerwiec, a co-founder of the conference, about how she came to comics as a medical professional, and why she believes that health care is everyone's business. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Why comics and medicine? What makes those two things a good fit?

There are a lot of wonderful answers to that question, which is why we love having annual conferences — because people come from all over the world to tell us their answer. In general, it seems that comics have the power to convey important information in ways that people who are dealing with issues in health care and caregiving find appealing to absorb.

One example of how comics are used in medicine and why comics and health care go together is that there's a long history of public health messaging through comics because they're accessible. They can potentially transcend language barriers — the visual appeal. They can take a lot of information and make it kind of quick and well-organized.

It’s also a great patient education tool, but what we found too is that it's an incredibly powerful tool for patients to use as a form of reflection and for storytelling about their experiences of illness. And then it's an incredibly powerful experience to bear witness to those experiences and kind of have that empathy connection.

And comics are being used to teach in medical schools and nursing schools and across many different areas of education — in and outside of health care.

And how did you come to health care storytelling through comics?

I came to it really out of necessity. I was working as a nurse at the height of the AIDS crisis in Chicago, and I would come home and I just felt this huge chasm between my everyday life and my work life. I was having a lot of trouble making a bridge between those two things. And I also was really having a hard time processing all of these intense sufferings, experiences, and these lives that were kind of coming to an end before me.

I had tried [writing those experiences through] text alone and that worked a little bit — like keeping a journal. I sometimes had occasionally tried images alone — making memorial paintings and painting screens in memory of people who I cared about, just sort of the symbolic language to remind me of things that were important to me about them. And then, it got to a point where, after doing this for five or six years, each of those individual methods were failing.

It came down to one day when I had to figure out how to get all of that out of my head. When I showed up at work, my patients deserved for me to be present to them, not my own suffering. I sat down with a blank piece of paper and I drew just this picture of myself and wrote above it, "I feel miserable." And then I put a box around it, and then I put another box, and then I just found myself combining image and text in this sequential fashion.

And I didn't set out to do it, but what I had done was I made a comic. And the thing that was really surprising to me was that I found myself in a completely different place than when I started. Something about the process of making that comic was transformative for me. And I just kept using that as a tool, as a nurse, to cope with what I was bearing witness to, and I found that it was really helpful.

And when did your experiments become more formal?

I ended up going into the field of Medical Humanities and Bioethics, in part because I really wanted to study why it is that certain ways of telling stories can be so helpful to us when it comes to illness. And I wanted to inform my comics, because I continued to make comics, and I knew I wanted to continue to do that.

But I wanted them to be better, and I wanted to inform them with a lot of theory and thinking about story and illness and health care. When I was working as a nurse, I was doing comics as a way of being present to the now and being able to be there for my patients. When I went into the academic side and started looking at this with a critical eye, that was when I started thinking about all the possible applications.

And then, I came across a book while I was doing my Master's studies called Mom's Cancer, by Brian Fies. And it changed my way of thinking. I just thought, "Wow.”

I got in touch through the internet with a few people who were starting to think along the same lines. And that's where we are today.

That was around a time when comics were coming to be more accepted in academia generally. Did you get a lot of pushback when you were trying to put comics and medicine together?

No. Quite the opposite. I could tell that I was in a really supportive environment at Northwestern, where some of the people around me saw the potential even more than I do. They were very encouraging to pursue it and pursue it thoughtfully. I've actually been surprised how embraced we've been. The Journal of Internal Medicine now has a graphic medicine page, and that really blows my mind because that's such a traditional medical journal.

Seattle has a huge global health and public health community here — we have PATH and the Gates Foundation and all that. And we also have a strong comics community as well. Is that why you chose Seattle for this conference? Or was it just our time? Or did you throw a dart at a map?

No, all that was absolutely a part of it. We had been hearing from some great Seattle creators, Mita Mahato being one of them. She’s our on-the-ground organizer [for the Seattle conference] who's, of course, a PhD literature scholar who has used comics in her teaching and really got invested in graphic medicine. But then at the same time, she is just an astonishingly talented papercut artist and comics creator in working on her own narratives, and she's been really active in the community.

And of course Meredith Li-Vollmer at the Seattle King County Public Health Department has come to our conferences in the past and presented projects that she's done with David Lasky in the public health arena. And Ellen Forney has been a keynote for us. We had so many people we knew in Seattle. When a couple of them said, "we think that we could get the support here to do this," we were really excited.

The registration is sold out, but you have a lot of free and open components to the conference. Do you have any advice for somebody who is thinking about attending some of the free programming? Do you need to be a medical professional to get a lot out of this?

I think anyone who has an interest in stories and health care and the ways in which we could approach how we think about health care differently would get a lot out of this. I think they will be really excited about what's happening in the graphic medicine community.

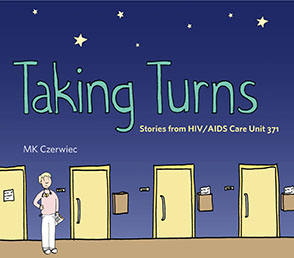

The title of my graphic memoir that just came out recently is Taking Turns, and what that title refers to is this idea that we really all are people taking turns being sick, and the divide between provider and patient is an artificial one — a necessary one, but an artificial one — and I think that it's important to remember that we all have a stake in this. Not just providers, not just caregivers, but all of us. And so I absolutely think that the public is welcome, and I don't think there's any kind of information anyone would need to know about graphic medicine before they come.

All of our keynote addresses are open to the public, and a number of the sessions. I think people will be really excited about this just right off the street.

Do you find yourself focusing any more on the political side of health care because of the AHCA and Obamacare?

We absolutely focus on it. We chose the theme of “Access Points” [for this year's conference] partly to think about some of those things. Who gets care? Who gets what kind of care? And how is that changing in this current climate? The threat to that access is more acute than ever.

I like to think that graphic medicine draws on the deep traditions of comics as both coming from the underground and bearing witness to stigmatized truth, but also the political tradition. The long tradition of political comics is alive and well. And access to health care, and comics about access to health care, are a big part of that.