In the recording studio with Sherman Alexie

It’s a cold and rainy March morning in Pioneer Square, and two men in a dark suite at Clatter & Din recording studios are chasing after a ghost. In the next room over, Sherman Alexie is reading his memoir, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, into a very expensive microphone. He’s recording the audio version of Love, which is set to be released in June, but the ghost hunt is getting in the way.

Here’s the problem: the director of the audio book, Jeremy Wesley, claims he can hear a high-pitched whine that piggybacks onto every word Alexie says into the microphone. He asks the audio engineer, Brian Sloss, if he can hear it. They ask Alexie to say a few words. Sloss first says he can’t hear the whine — it’s indistinct, Wesley says, just a bit of frizz hiding behind each word — but then, after a moment or so, he picks it up. “Yeah,” Sloss says. “Yeah, there it is.”

“We’ve got bad luck with the gear,” Wesley says. “Yesterday we had two cords go down. This is a bad way to start the day — it throws people off.” The two men start fiddling with the wires connecting to their elaborate computer setup, trying to determine the source of the ghostly whine. They get more flummoxed with every passing second. (For the record: my decidedly untrained ears can’t hear a goddamned thing, and in fact I thought Wesley was joking when he first started talking about the noise.)

For about 15 minutes, the hunt goes on as Sloss and Wesley float and discard a series of theories. Then they start replacing cables. Sloss goes into Alexie’s recording room down the hall, disconnects the cables connecting to the mic, and installs a fresh set. A moment or two later, Wesley and Sloss are sitting, expectantly, in their studio, waiting for Alexie to read. Their frustration is visible in their tense backs and jaws. When Alexie’s words come over the speakers in the studio, the two men relax as though they’re stepping into a sauna. The ghost haunting the words — wherever it came from — is gone, and recording can ensue.

Wesley has done a lot of work with audio books; he directed the audio version of Lindy West’s memoir Shrill, too. What does an audio book director do? Mostly, Wesley says, he listens to ensure that the author is “talking into the mic correctly, that we get the recording, and that it saves properly.” As Alexie reads his book aloud, Wesley reads along on a manuscript loaded onto his iPad. Whenever Alexie pops a “p” sound into the microphone, pauses too long between words, or flubs a pronunciation, Wesley makes a notation on his manuscript, reminding him to fix the error in production.

Alexie is one of the most talented readers on the planet, so Wesley says he’s got a pretty easy job of it this time. Yesterday, he recalls, Alexie “busted it out so quickly that we got even more done than we intended. We have the studio for four days, but he might finish it in three” because he’s such a professional in the recording studio. It helps that the book is of such high quality; Wesley praises the “caliber” of the work. “It’s just good,” he enthuses. The way he says “good” makes it sound like a word he cautiously preserves behind glass, only breaking it out when absolutely necessary.

During a break in the reading, Alexie invites me into the recording booth to look around. It’s dark inside, with no windows out into the studio to see Sloss and Wesley. Alexie’s recorded other audio books at Clatter & Din in studios that have a more traditional setup, with a line of sight between the reader and the engineers. Which does he prefer? Alexie looks around the booth, which is a little bigger than a closet. He says this works for him — especially given his memoir’s subject matter.

“It’s like a confessional” in the booth, he says. This way, when he reads, “I can imagine my audience. Sometimes I’m talking to directly to my mother. Sometimes, my wife and my kids.”

I step into the booth, and take another step, and then the silence subsumes me. It’s almost physical, this silence: you’re dipped into it, like caramel, and the whole world disappears and is replaced by the absence of sound. I blurt out a “holy fuck” at the unexpected vacuum, and Alexie nods. He recognizes that look of mild panic and wonderment on my face. When he’s in the booth, he says, “it sounds like I’m actually beside myself.”

The break ends and Alexie gets shut into the soundless room. Back in the studio, his voice sounds so clear in the speakers that he might as well be sitting there with us. He reads for a few minutes, and then Wesley makes a note on his iPad and steps on a pedal which puts his voice in the headphones Alexie is wearing in the booth.

Wesley asks Alexie, “could we do this one more time? You missed [the words] ‘dirty shirts.’” Alexie reads the passage again, inserting “dirty shirts” into the right space. He keeps moving forward through the text.

He reads a sentence and pauses, reads it again: “’Not even though I’ve been heavily marked by their scent?’ Did I write that sentence? That’s an awkward construction.” His voice pauses over the speaker, and then pops back in, with an audible shrug. “Wouldn’t be the first time,” he says.

Unlike most authors reading their own work for the audio book, Alexie is writing and rewriting parts of Love in the booth as he reads it aloud. With less than three months to go until publication date, Alexie says he wrote seven new chapters of Love while in the booth yesterday. “They’re short chapters,” he tells me. “The longest one is like four pages.” Wesley interrupts with a correction: “I think it was like eleven chapters.”

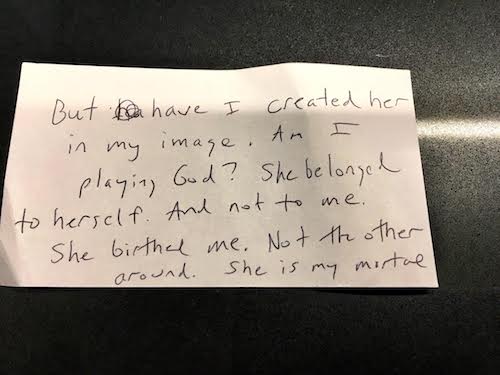

As he reads, poems burst out of him and demand to be added to the manuscript. Alexie sends me a photograph of one poem he wrote on both sides of an index card during a recording session:

At one point, Alexie starts making more mistakes: “I can’t get that rhythm right,” he says, saying one sentence over and over again. He reads the word “interviews” instead of “intervals.” He can’t land the phrase “when he was drunk.” He stumbles on the word “anesthetized.” He inserts the word “mom” when the text says “mother.”

Finally, Alexie realizes, “I’m not looking forward to reading the rest so I’m psychologically sabotaging myself.” He slows down a little bit and trudges forward until he gets to the passage he was avoiding — a youthful confrontation with his mother, when he returns to his room and sulks and punches the ceiling knowing she’s directly above him. After that, it’s back to normal. He relaxes and sinks into the words and makes fewer mistakes and embraces the text, and is embraced by it.