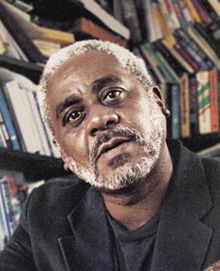

Talking with Charles Johnson about community, retirement, and writing a whole lot of books

Charles Johnson has been one of the most influential members of Seattle’s writing community. He’s contributed to the community in a number of ways — as a professor at the University of Washington, as a writer, as a friend to writers. Johnson recently joined the writing and literacy nonprofit Seattle 7 Writers, which donates to literacy organizations and donates books to readers around the region in shelters, detention centers, food banks, and other locations where people have need of good literature.

On Saturday, June 24th, Johnson will be headlining a fundraising brunch for Seattle 7 Writers at the Mount Baker Community Center. Every table at the brunch will feature one local writer, so attendees will get close personal contact with writers including David Schmader, Donna Miscolta, Claire Dederer, Claudia Rowe, and more. I talked with Johnson about the brunch and what he’s been working on lately. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Your Wikipedia page says you're retired, and I think you're maybe one of the hardest-working retired men I've seen.

Oh, that's why you retire from teaching, so you can get your art on your schedule 24-7. Artists never retire, but college professors do. That's true.

And how has your retirement been?

Well, it's been very good. I retired [from the University of Washington] in 2009, and I have been working steadily on all kinds of projects. I've published five books in the last two years, and I'm just putting together now the manuscript for next year, which is a collection of stories. It'll be my third short story collection.

My editor at Scribner just went over it. She didn't really have anything she had to do in the way of editorial work, but she just went over the stories and sent them to me. And so I'm going over her comments and putting together a proper manuscript to get to her next week. It'll be published next May. The title is Night Hawks.

All one word?

I'm breaking it up into two words, "Night Hawks." That's the title story, which is a story I wrote about my 15-year friendship here in Seattle with August Wilson. We had really great eight-to-ten-hour dinner conversations at the old Broadway Bar and Grill, which is gone now, on Capitol Hill.

In December you published a book about creativity and writing. And I wanted to ask if, at this point in your career, if you're sort of taking your teaching wisdom out into the world and teaching sort of in a more informal space?

Well, that's an interesting way to put it. The Way of the Writer evolved out of a longer book called The Words and Wisdom of Charles Johnson, which was a year-long interview that poet Ethelbert Miller did with me on every subject under the sun. He asked me 400 questions about everything, and I answered 218, and a lot of them were about the craft of writing, because he's a poet and also a teacher of creative writing.

And then we looked at that, and a couple of people commented, who had seen Words and Wisdom, that there was a book here that could be developed on the craft of writing. And I agreed. It was all there. I simply had to maybe revisit and update the essays that I did in response to those questions. And then I added a couple of essays that I had written on the craft of writing over the years.

So this book is essentially a record of my experience for 33 years as a teacher of literary fiction. That's about half my life, actually, 33 years.

But I still do teach. I'm going to work with people at the Spirit Rock People of Color Buddhist Conference in September. And I'm going to do two sessions with their teachers talking about the Buddha, Dharma, and how you can serve your communities with Buddhist philosophy and practice.

Buddhism has been an ongoing theme in your work. Has your teaching shifted over into a more spiritual place since you formally retired?

I've always been a very spiritual person. I've always been a Buddhist practitioner — my entire, really, adult life. I didn't bring that into the classroom with me; I would leave it outside the door. But I think it's pretty well known that I'm a Buddhist practitioner.

And so, people ask me questions about that and I'm happy to respond. It's all total, together, you know. Art is mind, body and spirit, and they all reinforce each other and serve the creative process, I think.

You recently joined the Seattle 7 Writers. Can you talk about what you like about them?

I joined on the invitation of Garth Stein. And I met Garth because every year we do the Bedtime Stories fundraiser for Humanities Washington, and he is the MC. I've written a story for them for every year for 18 years; it'll be 19 years this fall.

I've seen some of them and they’re wonderful. And you always seem so eager to be there.

Oh yeah. I think it’s a great experience. You create something new and it serves a good cause — the programs at Humanities Washington. And the new story collection coming out, Night Hawks, all of those stories except one were written for Bedtime Stories. Ten of the 11 were written for that.

And in my previous book, Dr. King's Refrigerator, five of those stories were written for Bedtime Stories. After I do them for the event and read it, my agent places it somewhere, and then very often it gets an award or it's reprinted or anthologized. So for me, the Bedtime Stories event is a perfect stimulus.

And with regard to the very, very good MC [Stein], he invited me to join the group because I think he's doing good things. The group is doing good things with writers and readers in Seattle.

And can you give us a little preview of what you're going to talk about at the brunch?

I want to talk to Garth a little bit before I actually do it, but my hunch is that what I'll do is I may read bit of something from the last book, The Way of the Writer, and then engage whoever is present in a kind of spirited Q and A about the creative writing process.

And there will be writers at every table of the brunch spread throughout the room, so that'll make an interesting forum to talk about writing.

Last March, I went to the Tucson Festival of Books. I was on a panel with Colson Whitehead, and then I was on a panel with my UW colleague David Shields, and another guy who wrote a book called Thrill Me.

But the morning before that afternoon panel, I spoke to writers about writing using The Way of the Writer as my springboard. It was just real. It's a roomful of writers because it's a literary festival, so I'm pretty familiar with that group — what kind of questions writers can ask. They ask the best kind of questions because they are immersed in the creative process themselves.

Lately I've been asking writers about community. Throughout your career, you've had a terrific commitment to community. You work with Humanities Washington, and you just joined Seattle 7 Writers, and you're very generous with your time. I was wondering if you think that a writer does have an obligation to a community — or does it depend on the writer?

I think you hit it when you said it depends on the writer. Some people are very eager to interact with other writers — to understand what they do, to do things with other writers that are for good causes. Like Humanities Washington, for example. I mean, I enjoy helping other writers, particularly younger ones, get published and get awards and colleagues.

I'm working right now with philosopher George Yancy on a book that he's going to do on Buddhism and whiteness, a critical race theory. I just alerted a lot of friends that I have in the Buddhist community, or the Sangha, to what George was doing. And maybe they'll make a contribution to it and make the book even richer.

I talk about that in The Way of the Writer, probably in the introduction. We don't live in isolation. I think we live in a world of interconnectedness with others. We might feel isolated sometimes; writing's a very lonely activity. You're doing this by yourself, usually, right? In a little room somewhere or, I don't know, wherever people write.

And you kind of forget that it takes a lot of people to get a book out there. The writer writes it, but then there's the editor who gives a good critical eye to something the writer might have missed. And there's the publisher, right? And then there's the bookstores. It really is a network, as Martin Luther King would say, a network of mutuality, that brings a book into being.

I've always been conscious of that, and grateful, too, and thankful for the people who enable a book to become a public object after it leaves the hands of the author. And maybe other writers don't feel that way, but I do think we're all conscious of the fact that we were given something by others, and it's very good, if we can, to give back.