Future Alternative Past: covering it

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Judging a book

A cover’s the first thing you see when you look at a book. Maybe the spine alone — a wash of color, font(s) spelling out its title and the name of its author (with any luck, legibly). You see more if the book is “faced out,” that is, displayed so the front cover’s facing you, and you’re getting the full force of the artist’s and designer’s skill. What can you tell at first glance?

For starters, expensive treatments such as embossing, cut-outs, and foil or metallic inks mean the publisher thinks they’ll be selling lots of copies. Traditionally, the publisher’s got an in-house team taking care of the cover business; traditionally, authors have little to say about how their books are packaged beyond, if the publisher’s feeling extremely gracious, a chance to nix the chosen art. Which Tor gave me with Everfair; editor Liz Gorinsky showed me a preliminary sketch done by the brilliant Victo Ngai and I pointed out that the human hand in it should be black. And she made it so.

But protagonists’ races aren’t always something you can tell from a cover, alas. “Whitewashing” is the term we use for this problem. For every piece of representative and lushly dark Kai Ashante Wilson or Nnedi Okorafor cover art, there’s a counterexample, such as the weirdly pale version of Lilith Iyapo shown on the original edition of Octavia E Butler’s Dawn. Of course that last book was published thirty years ago; nowadays, a mostly abstract or alphabetic cover like the one on Zen Cho’s wonderful Sorcerer to the Crown is the compromise.

Not that there’s anything intrinsically wrong with alphabetic cover designs — one of my favorites is the cover for Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, reproduced here on a t-shirt. But I contend it’s shabby of publishers to routinely use graphics to conceal information they think you shouldn’t have.

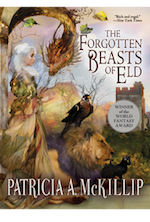

Because there are times they do exactly the opposite for the information they think you should. Goggles, top hats, and dirigibles on a cover signify steampunk; spacesuits and cratered, airless planetscapes signify “hard” science fiction; busty contortionists in jeans or leather catsuits signify “urban fantasies” about werewolves and private eyes. Delving deeper into this code, specific artists are identified with specific subgenres and even with particular authors: Thomas Canty with high fantasy, Kinuko Y. Craft with Patricia McKillip (I review a classic McKillip re-issue later in this column).

Publishers speak cover art fluently. If they want to.

Another thing you can usually tell from a book’s cover: who else thinks it’s cool. Traditionally, publishers are also in charge of soliciting “blurbs,” as the two-or-three sentences of praise bestowed by big names are called. The results can be edifying. If the book jacket prints a statement from Samuel R. Delany or Junot Diaz saying a debut novel is brilliant, I pay attention; if it’s lauded as amazing by someone who…isn’t…I pass it by.

So yes, often you can judge a book by its cover. But then there are those times when things go horribly wrong. The cover art for the first printing of Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life and Others has a clumsy Ayn Rand-paperback feel entirely at odds with the collection’s ambiguity and subtlety. “There’s a Bimbo on the Cover of My Book” laments a familiar filk song (folk songs for members of the SFFH community). “All too accurate,” one commenter proclaims of the song’s full lyrics.

One way around these messes is to self publish. Another is to publish with a small press such as Tachyon, Aqueduct, or Small Beer. In both cases authors are better able to plead their book’s cases to the judge and jury of the reading audience.

Couple of upcoming cons

There’s a first time for everything, including AfroComicCon, a Bay Area “comic book, art, media, science fiction, technology awareness, web TV, film, and writing convention.” You get all that for a ticket costing $7 to $30 — depending on which events you opt for. A free-of-charge Youth Community Day is promised also, though no details are available yet. Jaymee Goh and Zahrah Farmer Castillo are two of this fledgling con’s fourteen featured speakers.

VCON, on the other hand, has existed since 1971. This year’s VCON 41.5 is billed as a “relaxacon”: light on programming, heavy on socializing. It’s a format that will likely work both for longtime attendees who just want to hang out with old friends and newcomers who’d like to get a feeling for the con community. Structured only around the length of a movie or the rules of a game, VCON 41.5 could be a revealacon as well.

Recent books recently read

As noted above, recent covers for Patricia McKillip’s fantasies are almost always painted by Kinuko Y Craft. Except when they’re not; a new reprint of her groundbreaking World Fantasy Award-winner The Forgotten Beasts of Eld (Tachyon) is graced instead by Thomas Canty’s art. And why not? McKillip’s soaring prose, lyrics to songs our hearts have forgotten they knew how to sing, deserves Canty’s accompaniment. The feminist underpinnings of the book’s plot — a self-sufficient woman who refuses to be stripped of her autonomy starts a war she swore never to fight — deserve our attention now as much as they did in 1974, when Beasts was first published. If you’ve never read it, you deserve to. Or if, like me, you read it long ago and have made do since with a tiny but affordable mass market paperback, you deserve Tachyon’s elegant trade paperback edition, at least half as beautiful as McKillip’s story. Which sounds stingy as compliments go, but is actually extremely high praise.

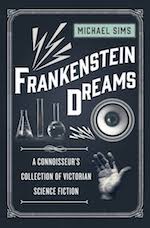

Frankenstein Dreams (Bloomsbury USA), a retrospective edited by Michael Sims, is fourth in his series of Victorian SFFH anthologies. The book begins with a detailed introduction, then proceeds to work by Mary Shelley, author of what’s arguably the first modern science fiction novel, and ends with Arthur Conan Doyle, whose iconic sleuth Holmes epitomized the scientific approach to mystery. In between these two Sims manages to introduce several authors less familiar to modern SFFH readers, or probably to modern readers of any genre. He also takes the somewhat regrettable liberty of excerpting a minor and wholly non-sfnal Thomas Hardy novel, justifying it as an illustration of the anxiety the time’s scientific discoveries provoked. Other excerpts — of Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas, of Shelley’s superb Frankenstein, of Wells’ The Island of Doctor Moreau, and of Stevenson’s Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde — may tempt the antho’s audience to read the complete novels they’re taken from. They stand up poorly to the real short stories appearing here, though, such as Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M Valdemar” or my favorite, Mary E. Wilkins Freeman’s “The Hall Bedroom.” Gender issues are addressed in “A Wife Manufactured to Order” by Alice W. Fuller, and racial prejudice in Edward Page Mitchell’s “The Senator’s Daughter,” but for the most part Frankenstein’s Dreams seem to center on explicit monsters and the implicit estrangement of members of the era’s dominant paradigm.