Thursday Comics Hangover: Blue collar special

On Labor Day, I argued that we need more blue-collar novelists. The thing that I didn't note in that essay is that there are plenty of contemporary blue-collar cartoonists — not because the comics industry is so forward-thinking but because the comics industry does such a poor job of compensating artists for their work. Unless they're a superstar name or someone who works on a number of different gigs simultaneously, the odds are good that your favorite cartoonist is either A) indepdendently wealthy or B) working multiple angles to make ends meet.

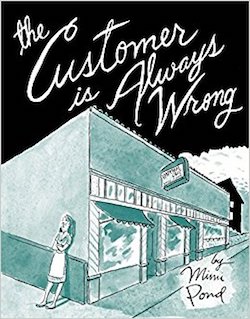

Madge feels pretty grown up when she scores a job at the Imperial. She's living with roommates, she gets a boyfriend, and she falls for the eccentrics who frequent the Imperial — on both sides of the counter. But soon enough, people start ODing on heroin, or doing too much coke and getting violent, or having brushes with the law. It's a coming-of-age story set in the school of hard knocks.

Tying together all of the anecdotes that make up Wrong is the work: waiting tables is the baseline of the book. Madge walks around with a carafe of coffee in one hand, chatting with customers, learning what she can about the world from the booths of the Imperial. Sometimes the kitchen is slammed and Madge has to try to charm her tickets to the top of the to-do pile. Other times it's slow and she shoots the shit with regulars. It's a book that's intrinsically tied to the dignity — and indignity — of work.

At nearly 450 pages, Wrong is a mammoth-sized comic. You'll have to take your time with it, and that's how it should be. It's a memoir that takes you through the days and nights of its main character, and it slowly transforms Madge in such a way that the reader barely notices until the transformation is complete.

Pond's art is perfect for this kind of serialized novel of a story: her art is cartoony but finely detailed. Madge's face is just a couple of lines, but Pond draws every stave in the row of chairs in the background. This makes the run-down glory of the Imperial, and of pre-tech-boom Oakland, an additional character in the book. You're not likely to read another comic this year that immerses you so deeply in the lives of a cast of characters, and these are lives — endearing, aggravating, tragic — that you don't see enough in modern fiction. Cartoonists like Pond are happily taking up the space that novelists have abdicated.