New Hire: Talking with DW about moving to Seattle, publishing his sketchbooks, and finding cartoonists from every continent on Earth

On Saturday, October 14th at 6 pm, the Fantagraphics Bookstore in Georgetown presents new work from three great young cartoonists. Denver’s Noah Van Sciver and Los Angeles cartoonist Joseph Remnant share the stage with a new-to-Seattle cartoonist who goes by the initials DW. Fantagraphics is releasing DW's very first book, a reproduction of a graph-paper sketchbook titled Mountebank.

DW is a serious and thoughtful young cartoonist who, in his spare time, co-founded and co-edits a comics anthology called Irene. He was kind enough to take a break from a visit to the east coast to talk to me on the phone about why he picked Seattle as a home, how he came to publish with Fantagraphics, and the responsibilities of being an editor of comics. This interview has been lightly edited.

When did you move to Seattle?

On July 7th. My friends, who drove me up, we left San Francisco on July 4th and we got to Seattle on July 7th.

How long were you in San Francisco before that?

Five years. I graduated from the Center for Cartoon Studies in 2012 and spent the rest of the summer in Vermont after that. On September 5th 2012 I flew out to the Bay Area and spent about eight months living in Oakland, and then moved over to San Francisco. So all told, it came out to almost exactly five years in the bay area.

Can I ask why you moved to Seattle?

I found San Francisco to be a very lonely place. It was a big problem for me there — connecting with people and feeling like I was part of a community, either on a personal level or as an artist trying to be amongst other cartoonists. I had given it my best shot for five years.

So it was partly running away from stuff there and just wanting to move onto something different, which I had been thinking about doing for quite a while at that point. But it was also about running towards something, because [Fantagraphics and I] had been working on [Mountebank]. That was about to come out about the time I made the decision to move to Seattle.

I already had several good friends who were cartoonists in Seattle and are part of a really rich, vibrant community. I checked with them to find out — I was like, ‘Is it still kicking? Is the cartoonist community still alive and well in Seattle?’ And they said, ‘Yes, it absolutely is. Better than ever. You should come for a visit it and see if you feel at home here.’

So I visited and then made the decision pretty much right then and there that I was going to give it a shot.

So Seattle does not have a reputation for being a warm and welcoming city to new visitors. I assume you probably heard to death about the Seattle freeze.

I think it should be called the San Francisco freeze.

I have heard about it, and I have not found it to be a part of my real-life experience in any way. I have found moving to Seattle to be an exciting, lovely, stimulating, warm experience. I feel really connected to the people. For the first time in a long time, I feel part of an artistic community, part of a healthy social world.

So I haven't had any problems with the Seattle freeze. I know it's legendary. You know I think as an East coast person, born and bred, I'm never going to feel completely at home on the west coast, which is part of the reason why I like living on the west coast. But I instantly felt connected to something in Seattle that I never felt in the Bay Area. It doesn't feel like work every day to feel connected to people, both on an artistic level and on a basic human social level. I've loved it so far.

Are there any cartoonists in the community who you want to especially highlight? Any cartoonists who were especially instrumental in your move?

Either before I moved here or who I’ve encountered since moving here or both?

Either.

Before, the two who were both my closest Seattle friends and are also two of the best cartoonists I know, are Ben Horak and James Stanton. Their work has been printed in the anthology that I edit. They’re both buddies of mine, and even if I wasn't close friends with them I would completely have nothing but good things to say about their cartoon abilities.

[Max] Clotfelter and [Tom] Van Deusen and Marie Hausauer — I didn’t know any of them personally... Oh, and Handa. Do you know Handa?

I don’t think so.

She's amazing. I was big fans of all their work before I moved here and now I'm becoming friends with all of them. I've had a chance to start to get to know all of them, and they're all really good people.

Probably my favorite Seattle cartoonist right now is Seattle Walk Report. Do you know her work on Instagram?

No! Seattle Walk Report? That sounds awesome!

Yeah, everybody should follow her.

Oh, and I forgot to say Marc Palm. Marc was the guy who helped me find a place to live, which was really important because I've become friends with all my roommates now. Marc, besides being a good cartoonist and a good guy, is such a pillar of the community.

As you well know, because you've been through all this with him, what he's accomplished recently with the left-handed drawing thing is something that is, to me, a major accomplishment for an artist. It's really inspiring the way he deals with adversity and adapts to his situation and turns it into something new. That ability to do that and make lemonade out of lemons is what I aspire to as an artist and a person. So Marc is a very important guy, both before I moved here and still to this day, as a friend and colleague.

So you went to the Center for Cartoon Studies, which basically means you are hardcore. That is not something you bumble into because you think you're going to maybe try this cartooning thing. You go there if you want to be a cartoonist for the rest of your life.

It's true. Yeah, it's like if you want to get your time's worth and money's worth out of it you have to be prepared to go hardcore with it — whatever that means for you as an individual. I think it would be pretty pointless to spend the money and the two years if you're not at least going to try to do it every day for the rest of your life, whether you have any intention of anybody seeing that work or not. So that's what I tried to do.

Have you always been a cartoonist, then?

On and off. I did it a lot when I was a kid. I've never stopped reading comics, my whole life. Especially newspaper comics. I've been really steeped in newspaper comics, from the time I could read. I was born in ‘83, and Calvin and Hobbes ran from ‘85 to ’95, so I was right in my formative years in that point where Watterson was also publishing a new Calvin and Hobbes in the newspaper every day. I would read the Philadelphia Inquirer comics page every day and always save Calvin and Hobbes for the last thing I read right before I left to go to school.

And I read super hero comics, graphic novels, and pretty much everything else. I read Maus when I was about 10. I was making a lot of comics and writing a lot of bad stories, and doodling all the time when I should have been focusing on schoolwork.

Then I drifted away from it. I never stopped, but [comics] got relegated to something I would do during class when I should have been paying attention to my teachers, or that I would toss off as a joke for friends. The main portion of my artistic energy went to other things like playing music, or making videos with friends. Things that entailed a more, by definition, social aspect because I think that's what I needed at the time.

When I was in my early 20's and I was working a nine-to-five job after graduating from college I found my way back to really making drawing an essential part of my life and started taking it seriously again. It was a few years after that I decided to go to grad school at CCS.

So how did you get involved with Fantagraphics?

Two years ago, I was coming up to Seattle to meet my mom because she was going to be there on business — this was when I was still living in San Francisco. It seemed like a natural thing to do to take time off of work and hang out in Seattle for a little while.

I figured since I was going to be in Seattle anyway I would see if I could pull some strings and try to get my foot in the door to just meet the people at Fantagraphics. I was really looking at it as a networking opportunity to try to get on their radar: let them know who I was, see if they had any constructive feedback about my work, put my work in front of their eyes.

And it turned out that they were interested in working on something together, so then we started to discuss what form would that take. I had some pretty strong feelings about that. They pushed back when appropriate, but they were very easy to work with and very supportive of my ideas for how this project should take shape.

What were some of your strong feelings?

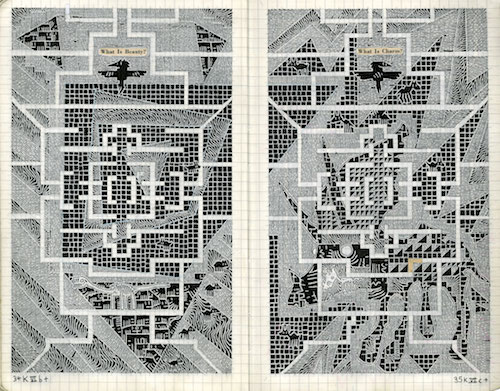

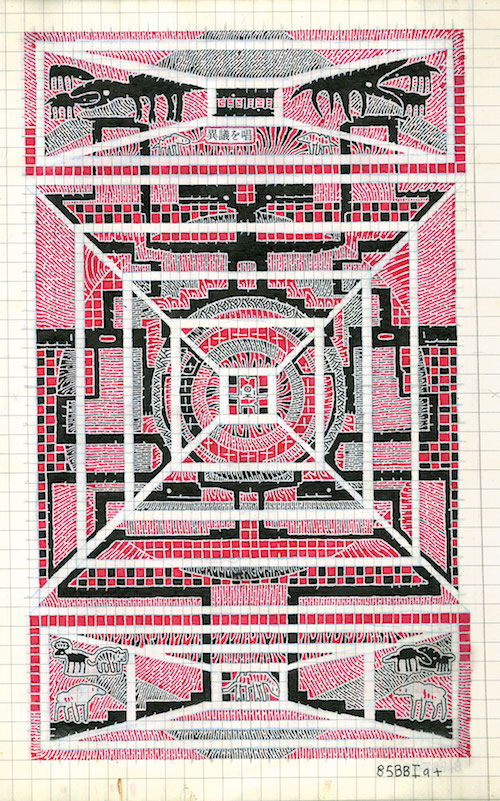

[Mountebank] is a facsimile reproduction of an actual sketchbook that I maintained for about two years. Because of the way that I conceived of and structured the work in that book, which was extremely organized and regimented and followed a strict set of rules, I felt that the work had to be presented altogether in sequential order, in the original order that it appears in the actual sketchbook, and that the concepts of the presentation should be a facsimile — as close as possible to the feeling that you're holding the actual book in your hands. A few people have commented to me, and I don't think that they're wrong, that [sketchbook reproduction is] a bit of a played-out concept at this point. Maybe the market got a little saturated with that kind of presentation, but I just felt like that was the only way to do this.

Working in a sketchbook has a very particular meaning for me. It's my preferred method of working and it helps guide my work in the direction that want it to go. I think that presenting this particular body of work — both because the pages do have a relationship to one another and because of the way they look on the original sketchbook pages — I think it's important that you appreciate that this is all coming out of a sketchbook.

It's kind of like finding that place where this work represents an overlap between comics and the physical feeling of the intimacy of leafing through someone's sketchbook, or seeing something that they're giving you permission to see that they've been carrying around in their bag with them for two years and scribbling in during their lunch breaks.

Yeah, I think there's an interesting relationship between cartoonists and their sketchbooks and their broader body of work. Nobody can really deny that Robert Crumb’s sketchbooks, which Fantagraphics has reproduced, have become a central part of his work.

Right. I've heard through the grapevine that Crumb himself was really skeptical about that concept. He thought it was kind of a dumb idea. I don't know if I have that exactly right, but he wasn't really into that idea. And people love those, right? [His sketchbooks have] become a central aspect of his entire body of work now.

Yeah, and there are other cartoonists, like Seth for instance — I prefer his sketchbook stuff lately to the stuff that he’s more intensely rendered.

I can see that. I don't know if you'd agree with this, but I think with that with him, his most recent comics have gotten so designerly. Which, obviously, he's one of the most talented designers alive. But they're so designerly and so polished that you end up kind of responding to that more than the emotional content, or the narrative content. Whereas with the sketchbooks there's like these flashes of really powerful emotion or something that cut through a little more sharply.

I'm trying to create a space where the work in the sketchbooks is the finished work, or there is no finished work.

Yeah, and there's a lack of self-seriousness in his sketchbooks that I like in contrast with his other work. But somebody like Chris Ware, who is really into design — I like his sketchbooks, but they are not as significant as Crumb's or Seth's.

You know what? I totally agree with that formulation. I think you're right about that. Ware, I do like the finished work better.

It's very interesting that sketchbook art is becoming part of a cartoonist’s career and body of work.

I think you're right. And so with me, to jump ahead a little bit, I'm trying to create a space where the work in the sketchbooks is the finished work, or there is no finished work. Choosing to work in the sketchbook doesn't mean that this is supposed to be private, or unpolished —although it probably does allow me to get away with a lot of mistakes that I wouldn’t be happy with if I was doing it in a different context.

I think you’re the first cartoonist Fantagraphics has published who they've made the sketchbook before the “real” book.

You might be right about that. If that's the case, that was them being really amazing, thoughtful, cooperative, collaborators.

Is the book that I am holding in my hand, literally right now — is this basically the object that you brought in to Fantagraphics when you visited two years ago?

Yeah. I brought in about three or four sketchbooks to show them, including the one that you're holding right now. That was the one that I always had my eye on. Even at that point, I thought ‘I want this book to be presented by somebody, hopefully Fantagraphics, as a complete work.’

From the movement that I conceived the structure for that book, and designed the system that would guide the content and flow of the book, I had always envisioned that particular sketchbook as being a unified work that would hang together as one object.

So to answer your question more fully, if I were to hand you the original sketchbook, which I'd be happy to do sometime if we ever were to meet, and you were to place it alongside your copy and flip to the same page it would be virtually indistinguishable except by touch.

I can't triangulate your work by just having this one point to work with. Do you develop individual ideas in individual sketchbooks? Does your style differ depending on where you sketch?

I sort of change the channel depending on what sketchbook I'm in. There are different sketchbooks that serve different purposes, and represent different meanings or contexts for me. I always maintain at least one sketchbook where I do stuff I probably wouldn't necessarily ever print, or maybe even wouldn’t show to somebody — real raw. Just letting my ID roam around the page and morad around and see what it can catch. Then with Mountebank, which was the name of the sketchbook — you know, you have to name your sketchbooks — Mountebank was conceived as the opposite of that.

Even though it was in a sketchbook, I wanted it to be a unified body of work where you do go on this journey as you flip from one page to the next, and before I ever made a single mark on the first page, I conceived of the system that would guide the rules and the content and the structure of what criteria have to be met on every page, and the order in which the pages go. I drew up a whole matrix to tell me when I got to each page, which criteria and rules had to be honored on that page.

Then, I would have to respond to those rules I had set for myself in the context of where I was at that point in the book and create that page accordingly so I would have room to improvise and play around. Going straight to ink, as I do, but would also have to be mindful of those rules and build everything I was doing around those rules so that each individual page would stand on its own compositionally, but would fit into the larger structure of the piece by obeying the rules of the matrix.

It's a really impressive book. I intend to come back to and reinvestigate it. But it seems like there are a lot of layers going on here.

Yeah, and I hope that not knowing what they all are and not understanding all of the criteria would be part of the act of enjoying the work. I don't want you to have to know all that stuff in order to understand the book.

Yeah, but it does seem like there is a definite form of logic.

There's one in my head. I know exactly, in my head, how it works. But to me, all of that logic, and the system, is a jumping off point for how to get started making the work, and how to direct my energy within the process of making the work. But in my opinion, it’s absolutely not essential, or probably even interesting, to someone who just wants to flip to a page and enjoy looking at the pretty pictures. You know?

Towards the middle of the book I you embark on what feels like a real investigation into the idea of what a panel is and what a panel can do.

Totally! The panel thing is huge. That was a big thing for me. You put that really beautifully, too.

You could view the entire page as a single panel or you have the lines in there that can be seen as sort of breaking it up.

Right, and sometimes the panel borders are respected as blocking off each panel as the discrete area, and sometimes they're not. So sometimes the breaking up of things into panels could, at the same time, make you want to look at each panel and "read" each panel in sequence. And then at the same time it might make you want to step back and look at the larger composition, because certain aspects of the composition respect those panels and those panel borders, and then other aspects freely traverse [the panel borders] with no respect for them. So that hopefully the entire page would hang together as an entire composition while also being readable, as it were.

And then also I think you could also view each individual square on the graph paper as its own panel.

I think in some cases I got away from that as I went on. I think towards the end of the book it got sort of zoomed out a little, which you could also say that about the book itself. So I guess you could look at it in these units of individual squares, individual panels, individual pages — and at every one of those levels I'm always also thinking about the level above. So as I moved towards the culmination of the project and was trying to get to the page count that I wanted for the final submission, I think I was getting a little broader in scope and starting to think more like a designer and less like a cartoonist.

We literally had artists from every continent in the world, including Antarctica, in one comic anthology.

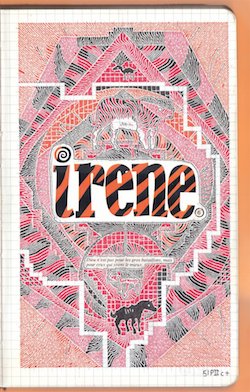

You are an editor of an anthology titled Irene, and I wanted to ask you about that. I've only interviewed a few people about editing comics. Generally they are very sort of blasé about editing in a way that literary editors are not. Like [Fantagraphics publisher] Gary Groth, for instance. He told me once that he did very little editing once the pages came in to him, because there's not much an editor can do with a drawn comics page, as opposed to working with text. I just want to ask you what it's like working on your book as an editor, and what kind of an editor you're like. I think that's a couple questions at once, sorry.

I can certainly answer the first part easily. In terms of working as an editor, I'm working alongside two of my closest friends in the whole world, and two of my favorite artists, Andy Warner and Dakota McFadzean. We are together editing and publishing this book that we co-founded, the three of us.

We're also designing the physical look of the book: we're doing the cover, the end pages, and the table of contents for every issue. We are talking to one another during the initial gearing-up phase for any given issue — who do we want to invite for this issue? We're all bringing different sensibilities to that, because we're three very different cartoonists in terms of styles, contexts, and communities that we work in. We're really close and we all respect and feed off of one another's work and respective aesthetics. But we're also all three of us connected to wildly different areas of cartooning as a medium.

So we're all feeding into this common stream, and then we're sifting through it: who do we want to invite, what overall aesthetic do we want to cultivate for a given issue, do we want more of one kind of artist over another?

Issue six, the most recent issue of Irene, we literally had artists from every continent in the world, including Antarctica, in one comic anthology. Which, we can't prove it, but we're pretty sure that's the first time that anybody's ever accomplished that with a comics anthology. We don't think anybody else has gone through the trouble to find cartoonists from Antarctica before.

So, there's that process of starting to put the issue together and conceiving of what it might be like. Then when the work starts to roll in, that's the most fun part. Because to echo Gary's comment on that — especially since we're asking people to be in this book and we're telling them up front that they have free reign once they've agreed to do it, to do whatever they see fit — we don't think we're in a position to push back and make changes or edits at that point. When they hand in the finished work we take what they've given us.

Along the way we have often had contributors who have asked us for editorial feedback while they're working on the project, and we love engaging with that and trying to be helpful with that where we can. But once the finished work has come in and we have all the work that we need to put an issue together the most fun part is the three of us getting together and debating the structure and sequence of the book. Like, ‘I really feel strongly that this particular story should be the opener because it will start off on a really strong note and it will set this or that tone for the book.’ Then choosing the last story is really fun. Every single issue we have one artist do all of the interstitials so that as you finish one story and begin the next there's a little breather page. We like to have one person do all of those interstitial breather pages for the whole issue. So that becomes this whole aesthetic consideration.

Yeah, and we're putting it together in this sequence that feels right for us and then the three of us are doing this sort of design and presentation for what the cover and end pages, and table of contents are going to look like and how they're going to create a functional house for all of those lovely comics.