Thursday Comics Hangover: Anders Nilsen is speaking in Tongues

Portland cartoonist Anders Nilsen is a special guest at the Short Run Comix & Arts Festival at Seattle Center this weekend. You might know Nilsen from his Peanuts-meets-Tolstoy epic bird comic Big Questions, or his heart-rending memoir of grief and loss, Don't Go Where I Can't Follow. But at Short Run, he's debuting his latest ambitious project: the first issue of a projected series called Tongues.

Nilsen describes Tongues as "loosely based on a trilogy by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus, of which two plays are lost and only dimly reconstructed by historians." This first issue is loaded with references to the Prometheus myth, but projected through a fractured lens of American military action in the Middle East, and with a talking bird and a monkey thrown in for good measure.

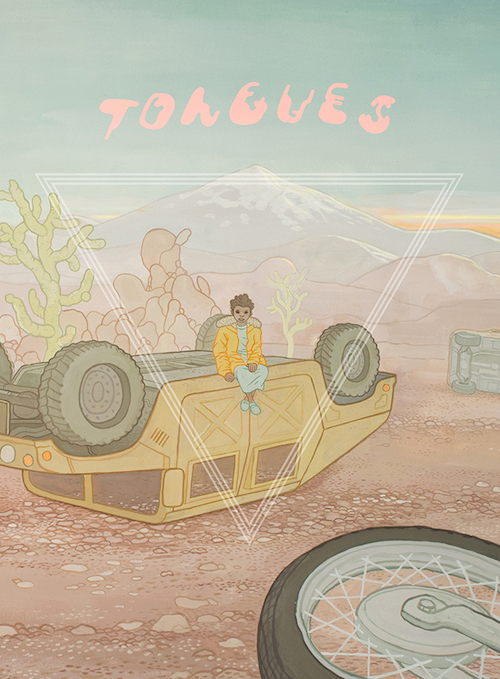

Tongues is the most beautiful thing Nilsen has ever made. The pages are colored in rich pastels that absorb your attention. The overturned and ruined military vehicles in these stories aren't left out to rot in a garish yellow comic-book wasteland; these deserts are pink and shimmering, with whipped-cream mountains looming off on the horizon.

The illustration in Tongues surpasses just about everything that Nilsen has ever done before. His characters are finely wrought, but they feel secondary in the narrative to the oddly shaped geometric panels and the dreamy backgrounds. We're more invested in what a lippy crow has to say ("The humans are an object of fascination to me, too," he says to a Prometheus figure) than almost every human in the book.

The stories in Tongues are short, but they do resonate with the throbbing weirdness of myth. The obvious Prometheus allusions are one thing — it's hard to see a bird eating the entrails of a still-living man and not recall the Prometheus myth — but these pages of finely wrought military SUVs overturned in the desert recall the devastation of the Iliad. The ruins of the US Army look not unlike the battered Coliseum of Rome. In those broken cars, a monkey argues with a human over a dwindling supply of rations. In this context, it's a clash of the titans.

Nilsen's great skill is finding the depth and the adventure in any subject, no matter how small. With Tongues, he's re-envisioning his place in the cartooning firmament. His sense of scale has changed; whereas before Nilsen obsessed over tiny interactions, he's now ready to create some myths of his own.