Every city a mystery

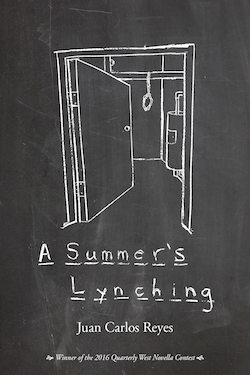

Seattle author Juan Carlos Reyes’s novella A Summer’s Lynching begins with a city:

After all, there will always be places on Earth where elevated things happen, where few people call each other by name, where voices sprinkle across pavement and seep into cracks, where stories are codified in the song of humming air conditioning vents and whistling manhole covers, flooded gutters and opening soda cans, aging Camaros and nagging door bells, store-light gnats and encaged dogs, pigeons smothering pavement in shadowy monsters and ten year-old littering sidewalks, and near endless repair projects that, in cycles of upended sewers and streets, feign renovations that never improve a city.

The voice in Lynching is noirish — that gritty coating on everything, that list of ugliness — but it’s a noir at an angle, like a cheap detective novel swallowed up in existential dread. Like a detective novel, the plot centers around a dead body, and how it got that way. Also like a mystery, the narrative is focused on the systems surrounding the death (police, the courts, all the different operations that the city needs to function on a daily basis.)

But unlike a mystery, Lynching isn’t really interested in who killed Isidrio Rafael, the corpse in the boiler room. It’s more interested in what happens after a tenant in Rafael’s building finds his body hanging in a common area. The book’s second chapter is narrated, in part, by Rafael’s neighbors. “Too many of us crowded the boiler room archway entrance, pressing into each other to see the man’s face, his hands, his feet,” they explain.

The perspective keeps shifting from one place to another in the city, and the narrative drifts further and further away from Rafael’s death. It’s like Lynching is the story of a haunting, told from the ghost’s perspective. As the novella unfolds, its interest in the specificity of narrative fades. Our attention wanders around the city, floating just above people so we can observe them from the air, a slightly distant ghost.

Lynching visits seats of power and utilities — one chapter is set at the power company, another in a church, another in a nest of bureaucrats. They’re all affected by the murder in one way or another. The city that Reyes builds alternates between interested and disinterested in the murder. It’s kind of like this:

Silence inside a library always precipitates a clamor outside of it to where the sound of the whipping city banner frantic on its flagpole is as loud and screeching as the brakes on a passing bus.

The less a city’s system is involved with the murder — a high school, say — the higher-pitched our curiosity becomes.

In the end, the city that Reyes builds is a lot like our own: it’s too big to comprehend, but too small to truly lose oneself in. In a city, nobody is really a stranger to anyone else. We’re all interconnected in one way or another, even if we’re cloaked in anonymity. If you stay in a city long enough, the body in the boiler room will likely belong to you.