Thursday Comics Hangover: From a roller rink to the stars

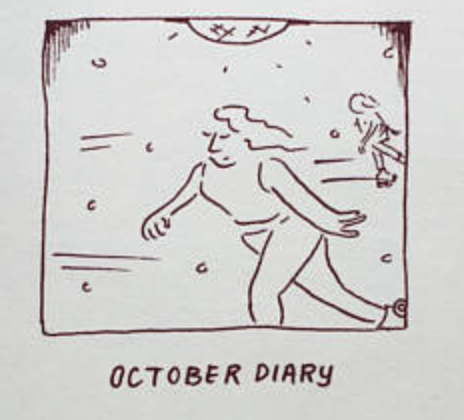

Natalie Dupille works along a wide spectrum of cartooning. Her diary comics — as seen in her most recent collection, October Diary — are sketchy and minimalist. It's remarkable the information that Dupille's cartooning can convey in with so little. Look at this image from the cover of October Diary:

Now consider how amazing it is that your eye can assess that image and immediately determine that it's set at a rollerskating rink when all you can see is exactly six motion lines, an eighth of a disco ball, a single rollerskate wheel, and a background figure. Dupille's entire head on the cover of the book is made up of exactly eight lines: one arrow of a nose, a swooping chin, a concentrating dot of a mouth, two eyes tight in concentration, and then three wavy lines marking her hair flowing in the breeze.

Some might think this rough sketch style of art is simple, but it is in fact inordinately difficult. When you draw with fewer lines, as Dupille does in her diary comics, that creates a tremendous pressure on the artist to make sure that every line is exactly the right line.

The writing in these diary comics is perfectly complementary to the art. Dupille catches a single moment in her day and rounds it out using exactly the right images. She notices how abusive guests at a dinner party behave toward the female voice coming out of an Amazon Echo speaker, for instance, or a blandly inoffensive statement at a corporate meeting can trigger memories of Donnie Darko.

These are tiny moments, but they are titanically tiny moments. They feel neat and self-contained and somehow expansive enough to swallow a reader's brain whole. One page of silent sketches of Dupille's cats and a caption reading "Sad & listening to Graceland on repeat" has somehow taken up residence in my head the way a good pop song does; I'm currently thinking of this strip six to eight times a day.

But there's a flip side to Dupille's work, on the other end of the spectrum from her sketchier comics. Her more rendered work features what appears to be watercolor, adding a delicate and vibrant life to her lines. These painted strips tend to focus on nature and science, and they demonstrate Dupille's boundless curiosity and enthusiasm for learning.

In Huckleberry Pie no.3: Selected Comics 2015-2016, Dupille lays out a two-page spread about the sex lives of banana slugs and earths, and it's a joyous, fun pair of strips. (Banana slugs, she tells us "frequently eat each other's penises after sex. No one really knows why, but we're accepting of most fetishes here in Seattle.") Another, more personal strip details the construction of a cob oven as part of Dupille's attempt to get closer to the land. Readers will find Dupille's attempts to understand the world around her to be infectious; her unabashed geekery is wildly appealing.

Total Lunarchy, a self-described "Zine About Space Dust and Other Important Extraterrestrial Matters," expands Dupille's curiosity into the chilly depths of space. Specifically, she focuses her curiosity on the clingy dust that has plagued the few astronauts we sent to walk on the moon. Lunarchy is about all the things we don't know about the moon. Specifically, she examines why static cling and magnetic fields combine to make the moon inhospitable to our attempts to set up base there.

Dupille is at the top of a very short list of cartoonists who are gifted at explaining science in a fun, approachable way. Lunarchy came out of a collaboration between Dupille and UW research associate professor Dr. Erika Harnett, and hopefully it's not the last foray Dupille will make into the sciences. The universe is complex and confusing; we could use more guides like her to illuminate the darkness with funny and informative cartoons.