Talking with Matthew McIntosh about the rhythm of incorporating videos into print books

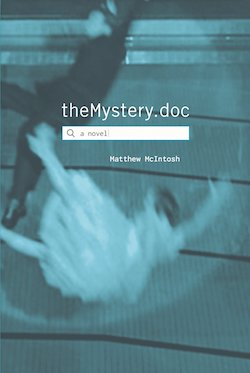

On Thursday, December 14th, I interviewed author Matthew McIntosh at Elliott Bay Book Company about his remarkable sophomore novel, theMystery.doc. McIntosh is the kind of author who invites the word "reclusive." There are almost no photos of him online, and he has kept himself cloistered away for over a decade working on theMystery.doc. He doesn't take part in group readings, or offer freewheeling chats on Twitter, or have a Facebook page. In fact, the Elliott Bay event was the second of only two readings he did as a part of theMystery.doc's launch.

But McIntosh isn't antisocial or even a little bit chilly, the way you'd expect a so-called reclusive author to be. In fact, he's warm, and charming, and very open about his process. For this event, McIntosh read over a series of videos taken from the book in a 20-minute presentation that incorporated science fiction and spoken word and experimental fiction.

It was a unique performance to celebrate a unique book. theMystery.doc is a behemoth of a thing, a surprisingly readable postmodern novel that is set in the early 2000s but which spans centuries; a realistic book about the dawn of our modern technological age that is stridently, proudly, a book that exults in its page design and corporeality; a big, ambitious book that doesn't have any of the ego or swagger of the typical Big Books by young Franzen wannabes. The book is full of video stills and blank pages and codes and just about every visual trick you can imagine, but it doesn't feel flashy or gimmicky like, say, House of Leaves. Instead, it feels like a book about The Way We Live Right Now. What follows is an excerpt of our onstage conversation.

My ideal version of the book actually turned out to be exactly what the book is. Even when we were doing the ebook — and the ebook by the way, comes free with hardback purchase — when my wife coded this ebook, we were talking about doing that, putting video in there. But that wouldn't really represent what the book is.

So that was a consideration, but I felt like I liked having the time. So much about the images in the book is about time, and so when you come to a scene, or come to a sequence of stills, for instance, there might be stills that will take you 10 to 20 pages to go through.

And so I wanted people to become immersed in the book. I want time to be an issue with them, so that their experience with time, and with that image itself, is part of the experience. I want them to stare at it as long as they want, and never to know what's coming next. If you were to incorporate video, readers would just watch it until it plays out, whereas if you take five stills, you can watch the progression of that time happening.

Video would be passive as well, and that would change the implications of reading and experiencing the book.

Exactly. So, for instance when — towards the end of the book — when the male character turns and runs, he does this in the guise of Jimmy Stewart. It was important in the first page of the sequence to show him sideways, looking and turning and running. The video was so fast that that first moment almost gets lost. So to have it in still form on a page, it’s almost like it’s eternal, in a sense, on that particular spread.

You kind of answered this a little bit, but there were other elements with and the number of blank pages between passages and images, for instance. When people write and draw comic books they worry a lot about the rhythm of the page, and what the reader sees on every page turn and things like that. Was that something you considered?

Absolutely. No question. No question. The design of the book took so long, and was so meticulously done. [My wife and I] had this thing we would call The Turn. And what that meant was on this particular spread, I want the reader to see this particular image. So that means sometimes you have to go back through the design of maybe 20 or 30 pages before it, to make sure that all the text is flowing at that particular rhythm to leave you at that moment where you turn and discover that image.

I wanted to have all of these turns to be surprises. And so every single spread was worked out meticulously — with rhythm, with timing, and with what the reader sees, and what they haven't yet seen.

What was interesting about this project was that every time that we ran up against something that we needed to change — it was never demanded about the text; It was usually running into permissions issues for certain [images] — it turned out better. And so throughout the project I became full of faith that any time I had to do something that was painful because this was the way it was supposed to be, I always had faith that it was going to turn out to be better. And I believe that it did, every time.

Also the book is full color inside, which I'm not sure would have even been technologically possible ten years ago at this scale. Was that a hill you were willing to die on?

Oh, yeah. It was understood. This was going to be in full color, and no edits. Which was a really ridiculous thing to ask. No one would ever do that! Publishing right now is really constrictive — especially with things that are going to cost money, because it's a hard environment to sell literature anyway. And this book costs — I believe it was probably five bucks a copy more than your average book. And yet we only have to sell it for 35 bucks, which is a pretty good deal. And you get a free ebook!

So we thought, ‘well, let's just see if Grove will do it. Grove published my first book without any edits. They were just awesome. And so I asked my agent to go ahead and send it to them, and she did, and when she called back she's like ‘he wants to publish it.’

And I said, ‘that's wonderful. Too bad he's not going to be able to because of the color.’

And she says, ‘he said “Of course we'll publish this in color! Obviously.”'

Every author I've talked to about Grove Atlantic is thrilled with them as a publisher. So I think you you you've got lucky on the first try.

Yes.

There are big books, and then there are there are big books like this that feel like the author just like poured themselves into it entirely. Given the amount of time that it took to produce the book, and how much control you had over it, did you did you feel drained when you were done? Do you have anything anything left in you for a next project?

I hope so. I think it's going to be definitely different. The things that I've been working on now are a lot different. You can only do this kind of thing, once I think. It was such an immersive experience writing it. I basically did nothing else for 12 years — just worked and worked and worked on the book. And that was the only way to do it, I think.