Whatcha Reading, Kevin Craft?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Kevin Craft is the director of the Written Arts Program at Everett Community College, a poet, and longtime editor at Poetry Northwest. He's also our Poet in Residence for January.

What are you reading now?

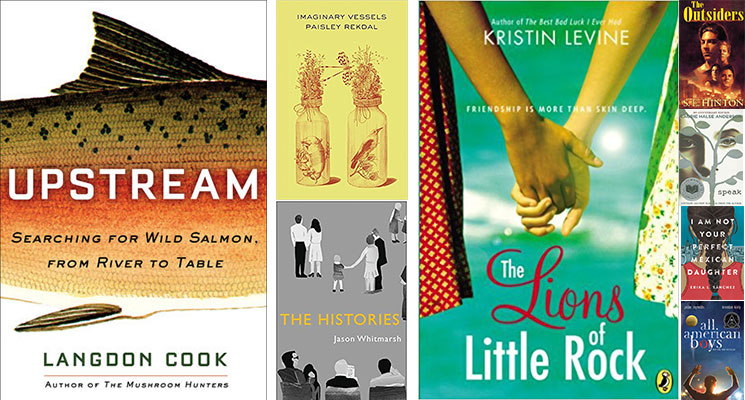

I'm just finishing Langdon Cook's Upstream: Searching for Wild Salmon from River to Table. It's an adventurous book — a wilderness of reportage, zigzagging all over the Pacific northwest, from Sacramento, CA to Cordova, AK, from the mouth of the Columbia to the source of the Snake, investigating in detail the history and current status of wild salmon populations. We get the big picture from this book: Native practices, the plundering greed and hydro-technical faith of Euro-settlers that caused salmon populations to plummet, the mixed blessing of the hatchery programs, the wild runs that remain. Cook connects it all to the way we live now: how salmon finds its way to supermarkets and restaurants and backyard grills. His prose is colorful, punchy, brisk — driven by a profound if understated sense for the tragedy of environmental degradation, though his real skill is hooking in the many fascinating, territorial characters who make a living around salmon, bringing their hopes and struggles for a sustainable future to the page.

What did you read last?

I recently finished reading Paisley Rekdal's Imaginary Vessels (Copper Canyon Press, 2016), alongside Jason Whitmarsh's The Histories (Carnegie Mellon Press, 2017) with a group of poetry students. I was interested in exploring what is sometimes called "documentary poetics" from two very distinct angles. Rekdal's book is a brilliant example of this kind of writing: it is many documentary angles in and of itself, including a suite of recombinant sonnets written in the voice of Mae West, and sequence of sonnets paired with photographs of anonymous skulls found buried in a Colorado state mental institution. The abiding pathos with which Rekdal restores these lost voices, the comical and the tragic, deepens our sense of what poetry, as vessel and vicissitude, can accomplish in a time when public memory is all slippery slope and sloppy lies. By comparison, Whitmarsh's table of contents (most begin with the title "History of...," such as "History of Therapy" and "History of Language") reads like the course curriculum of an eccentric liberal arts degree. Most are prose poems, short fables of modern life infused with wry, quiet humor. The prevailing voice is detachment — the dead-pan mode of Lydia Davis comes to mind — detailed like a scientific proof of some elusive emotional experience. As "documentary," these poems remind us that the facts of history may be hard to nail down, but we live inside our own fictions anyway, and we're better off learning how to navigate the absurd than pretending the world can ever be made right or whole or perfectly understood.

What are you reading next?

I have a number of books lined up for a new course I'm teaching in Young Adult Literature, starting with Kirstin Levine's The Lions of Little Rock. It's such a great, eye-opener of a story, depicted in smart detail from the perspective of a shy middle school girl struggling to find her voice. I plan to revisit The Outsiders, and move from there through some recent classics and hopeful bestsellers in the genre — Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak, Erica Sanchez's I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, Reynolds & Kiley's All American Boys, and others like it. Finding voice is a natural theme of adolescence, of course. So is parsing right from wrong, learning how to recognize truth, forming moral character and judgment. I'm interested in seeing how these themes play out in stories addressing social justice, group adhesion or exclusion, racial segregation, gender conformity, the works. I've got my hands full, no doubt. We'll see how it goes — I'm excited to discover what my students are thinking and seeing now.