Thursday Comics Hangover: The shaggy depths of outer space

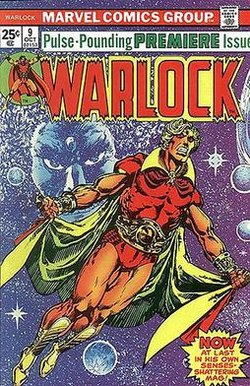

One of my favorites from that time was Jim Starlin's Adam Warlock series, a blessedly self-contained adventure of a space messiah who ultimately had to confront his twisted mature self. (In the 1970s, the Warlock story had a beginning, middle, and end, which was a rarity in serialized superhero comics. In the 1990s, Starlin revived Warlock and put him back on the intellectual property merry-go-round. As far as I'm concerned, the character stayed dead.) The book was visually wild, conceptually bold, and as cerebral as it was fun.

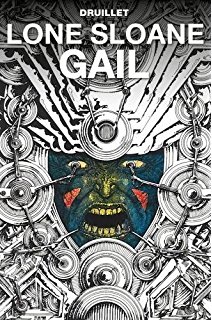

What I didn't know when I first read those cosmic superhero stories was that in 1970s France, an artist named Phillippe Druillet was creating a line of wild cosmic adventures that made its American counterparts seem as pedestrian as a Garfield comic strip.

Gail is a sexy, vivid fever dream, a story of pure evil trying to exert its will on the universe. The panels are angular and detailed down to the very last millimeter: a dimension of fractal skeletons; an emperor languishing on a throne in the aftermath of an orgy; a foreboding castle that stretches miles into the stratosphere, with a real photograph of a woman's face embedded into the front of it.

Our hero, Sloane, is not as grandiloquent as some of Marvel's more pompous cosmic heroes ("Go fuck yourselves!" he roars at the bad guys at one point.) But he's every bit as tenacious, venturing to the land of the dead to confront his opponents and upend the evil empire using just his wits and existential angst as weapons.

I'm not entirely sure what's happening at every point in the story, but that's not a strike against Gail. These cosmic books don't always follow the simple rules of cause and effect. Instead, they're examinations of what it means to be alive, to make moral choices in the universe, to carry the resonsiblity of existing. And Gail commits to the airy spirituality in a way that its American cousins could never manage. You'll never look at Adam Warlock the same way again after you read the adventures of his bonkers French cousin.