Tomorrow night, watch poetry make the jump to the big screen at the Cadence Video Poetry Festival

When Seattle author Chelsea Werner-Jatzke started working with Northwest Film Forum to put together a video poetry festival, she recalls NWFF administrators saying that "it'll be really important to define what video poetry is." At the time, Werner-Jatzke recalls, she thought that would be "no problem." But as she worked to curate the month-long festival of screenings and educational programming, she realized that she couldn't easily define the form.

In fact, describing video poetry in words, she says, is really difficult. "It's not a poem that someone made into a video," Werner-Jatzke says. It's a lyrical video, a poem in moving images. Just as you can't throw a bunch of indents and hard returns into a wall of prose and call it poem, you can't just put some images of flowers onto a screen and say it's a video poem. "It's a relatively new art form, as far as writing genres go," she tells me, and there are debates among purists about how far the form can be stretched before it breaks.

Werner-Jatzke's journey into video poetry began about five years ago, when a fellowship at Jack Straw Gallery inspired her to incorporate multimedia work into her writing. "I hadn't set out to make a video poem when I started to make one," she explains. "I had a piece that needed to be a video piece. I guess I was trying to figure out how that fit into my larger writing identity, and that's how I became enmeshed in video poetry."

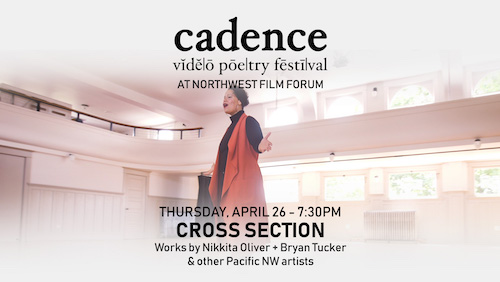

Tomorrow night, the final screening in the Cadence Video Poetry Festival is taking place at NWFF. In addition to video poems from all over the world, the screening will include new work produced in workshops over the past month at the festival by Northwest artists. Under the guidance of video artists like Gretchen Burger and poets including Nikkita Oliver and Shin Yu Pai, aspiring video poets have learned how to communicate in new media.

"I'm excited about seeing the workshop pieces, as a workshop participant as well as a producer of the festival," Cadence producer Rana San says. "It was cool to see how everybody took to the challenge. Filmmakers who hadn't had faith in their writing started writing, and writers were picking up the camera."

Werner-Jatzke is looking forward to "Triptych," a new work by Barrett White, and a film called "PoemVideo," which she says is "short and sweet, rooted in sound poetry and visually sort of simple in a wonderful way - some visual overlays but carried mostly by the delivery of the text and the music." She also says a new work created by Seattle poets Rachel Kessler, Sierra Nelson, and Britta Johnson will likely thrill audiences, and "Royaltee," by Kamari Bright, "incorporates text elements that add extra meaning to the spoken text she recites in unexpected and powerful ways."

But purists will continue to grumble: is a poem still a poem when it's in a video? Does poetry lose its essential poetry-ness when it's removed from the page? Werner-Jatzke recalls a moment that clarified that question for her at the Cadence festival kickoff screening earlier this month. "Nikkita Oliver pointed out that her writing is generally disembodied from the page," she says. As a spoken word poet, Oliver "doesn't draft on the page," and her poems often don't ever make it to paper. "I had to adjust my own framework" when Oliver said that, Werner-Jatzke says. "I think about literature as the written word, but literature is from a spoken tradition."

It's an enticing thought: If writing could shift in a relatively short amount of time from a spoken tradition to a written one, who's to say that the artists taking part in Cadence aren't helping along the next big evolutionary step?