Thursday Comics Hangover: What he's fighting for

With a very few exceptions, superheroes have always been portrayed as defenders of the status quo. It's a superhero's job, at the end of the story, to return the world to something like the condition they found it in at the beginning of the story. On a very basic level, they're opposed to change and to protest and to evolution.

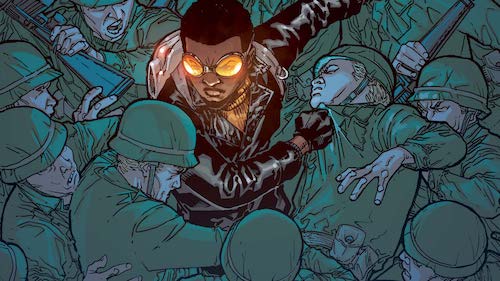

You can't help but feel bad for Jason Fisher, the jetpack-wielding superhero at the heart of screenwriter John Ridley's comic The American Way: Those Above and Those Below. Fisher is doing his best to save lives and serve the law. But as a Black man, Fisher is held to standards that white superheroes like Batman avoid. When Fisher catches an armed Baltimore radical in the first pages of the book, the Black residents of the neighborhood immediately label him a "sellout."

It only gets worse from there. Someone else calls Fisher "a traitor" and "a tool of the money class." And when a Black man calls him an "Uncle Tom," Fisher snaps back: "Read the book. He died protecting people. What the hell did you ever do?" Set in the 1970s, Those Above and Those Below is a deeply political story about revolutionaries and burnouts and everyone else who falls in between.

As you might expect from the writer of 12 Years a Slave, Ridley's script is taut and nuanced: you won't find a bunch of obnoxious 1970s references added in for unnecessary atmosphere. It's very obvious that America is being torn apart in this book, but Fisher doesn't have to yammer on about the Nixon Administration's excesses to convey the paranoia or the claustrophobia of the time. The art, by Georges Jeanty, is dense and detailed. I'd like to see a little more attention to facial expressions and physical differences between characters, but the action is clear and the storytelling is impeccable.

If you enjoy a good superhero story that doesn't shy away from the weird politics of the genre, you'll very likely enjoy Those Above and Those Below. But it's not the cynical, Frank Miller-style deconstruction of the genre you've come to expect from "adult" superhero stories, either. At the heart of the story, Fisher's decency shines through: he's someone who wants to help, and who doesn't shy away from the question of whether his help is wanted — or even needed. More superheroes should ask themselves that same question.