Thursday Comics Hangover: More than Crumbs

I'll admit, I'm not a huge fan of the jam comics made by the husband-and-wife team of Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Robert Crumb. The ironic cutesiness of those comics is nearly indiscernible from real cutesiness, and the juxtaposition of Crumb's formalist rigor next to Kominsky-Crumb's primitive illustrations is only good for a momentary thrill, and not a continued investigation. For a few years, Drawn Together, the collection of the married couple's collaborations, has been the only work of Kominsky-Crumb's in print.

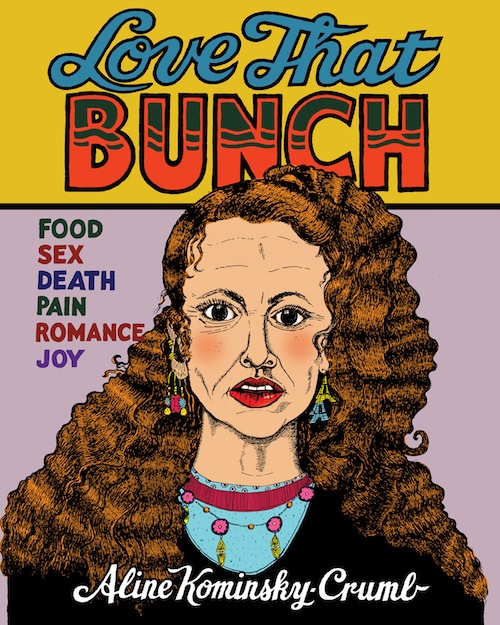

Thankfully a new reissue of Kominsky-Crumb's solo comics, Love That Bunch, reminds us that she's a cartoonist in her own right, and not simply an extension of her husband's drawing hand. Bunch collects her early work from the 1970s and 80s, and it also includes a long new story, "My Very Own Dream House," that looks back on Kominsky-Crumb's childhood.

The act of simply flipping through Bunch can teach you a lot about Kominsky-Crumb's evolution as an artist. Her early work looks more like traditional comics, with smaller word balloons and more room for the art. But as you scan through the chronological progression, you can see words start to spread throughout the comic, like a mold outbreak on clean white tile. Eventually, Kominsky-Crumb's narration dominates every page, with up to six individual word balloons per panel. The drawings become smaller and smaller, focusing more on figures than backgrounds or settings.

But when you flip to "Dream House" at the end of the book, you can see Kominsky-Crumb's cartoons have come full circle: once again, she's allowing more room for her art to breathe, and she's not bombarding the reader with too much over-explanation. (One of my favorite panels is of Kominsky-Crumb's daughter, Sophia, vomiting while shouting "I HATE YOU, FRANCE!")

Kominsky-Crumb made her name with a kind of brutish honesty that at the time felt revolutionary. Not a lot of women were openly and frankly discussing sex and periods and body image issues when Kominsky-Crumb started out. And the fact that she illustrated these taboo stories with crude illustrations that didn't look traditionally beautiful only angered the establishment even more.

In retrospect, though, those early diary comics aren't really shocking at all. Looking back over four decades at the strips that originally had a kind of punk rock allure, they instead feel a little bit quaint. That's progress for you.

Instead, the strength of Love That Bunch lies not in striking moments but rather in the accrual of many such moments. It's a compelling and comprehensive account of what it was like to be a young woman at a very particular time, and it comes with its own meta-commentary about how Kominsky-Crumb feels about the work after nearly a half-century has passed.

If you asked me when I first read Kominsky-Crumb's comics in the 1980s whether I'd still be thinking about her work in 2018, I would've laughed at you. But these stories have aged well as a very personal document of a very strange moment in American history, while Robert Crumb's work has lost some relevance in my estimation. Who knows? Maybe in fifty years, young people will declare Kominsky-Crumb to be the real comics visionary in the relationship.