The Sunday Post for June 17, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

My Romantic Life

This, by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, is a glass bullet of a piece that’ll leave shards all through you regardless of where it explodes.

The second time I did porn it was with Zee, when we were boyfriends, and I’d just remembered I was sexually abused, so I was taking a break from sex, but then Zee called me to do the video because his costar showed up too tweaked out — I did it because I needed the money, but then Zee got upset when I couldn’t come, and I felt like a broken toy. Which is how I’d felt with my father. When I walked out into the sun after that first video shoot I just felt totally lost, like I didn’t even know where I was and why was it so hot out, maybe that’s why I felt so dazed.

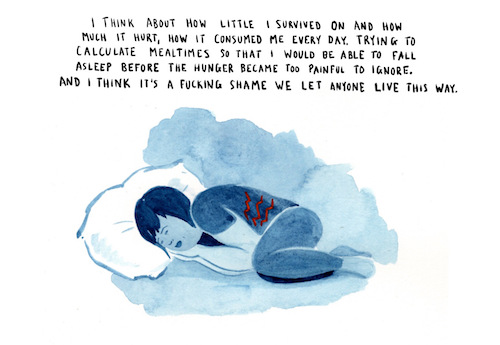

The Difference Between Being Broke and Being Poor

Erynn Brook (words) and Emily Flake (pictures) have made a softly lacerating visual essay on the distinction between not-having-money-right-now and not-having-money-period. Relevant, unfortunately, to Seattle’s interests.

What If I'm Just a Minor Writer?

Karl Taro Greenfeld had my sympathies from his first line: "I’m not who I was supposed to be." Yet: there are dozens of books by "minor" writers that I read over and over, because they help me survive. Do we all dream of becoming “great” writers (those of us who dream of becoming writers at all)? What’s wrong with just writing well? Or even — just writing?

I dreamed of writing novels that transcended time, that perhaps would someday convince a boy or girl that he or she should become a writer. Like a mother spider who births a thousand spiderlings for only one to survive to motherhood herself, perhaps this is how writers as a species survive. We all dream the same dream, to become important writers. Most of us never achieve it.

A Company Built on a Bluff

Courtesy of Reeves Wiedeman, a crazy-fascinating look at how Vice co-founder Shane Smith sold a particularly bro-centric idea of cool to round after round of investors, transforming an underdog counterculture paper into a media empire. Some of these stories are already well known (like the “non-traditional workplace agreement” and the New York Times investigation into sexual misconduct), but this pulls it all together, and says as much about what media consumption, creation, and investment are becoming as it does about Vice itself.

On the morning of the Intel meeting, Vice employees were instructed to get to the office early, to bring friends with laptops to circulate in and out of the new space, and to “be yourselves, but 40 percent less yourselves,” which meant looking like the hip 20-somethings they were but in a way that wouldn’t scare off a marketing executive. A few employees put on a photo shoot in a ground-floor studio as the Intel executives walked by. “Shane’s strategy was, ‘I’m not gonna tell them we own the studio, but I’m not gonna tell them we don’t,’ ” one former employee says. That night, Smith took the marketers to dinner, then to a bar where Vice employees had been told to assemble for a party. When Smith arrived, just ahead of the Intel employees, he walked up behind multiple Vice employees and whispered into their ears, “Dance.”

Punching the Clock

We’ve all worked a bullshit job — seemingly or truly pointless labor created to fill paid hours. Here’s David Graeber on why the already noxious state of affairs in which another person owns one’s time becomes so much worse when they use it badly.

Most societies throughout history would never have imagined that a person’s time could belong to his employer. But today it is considered perfectly natural for free citizens of democratic countries to rent out a third or more of their day. “I’m not paying you to lounge around,” reprimands the modern boss, with the outrage of a man who feels he’s being robbed. How did we get here?