Thursday Comics Hangover: The quiz kid raises a family

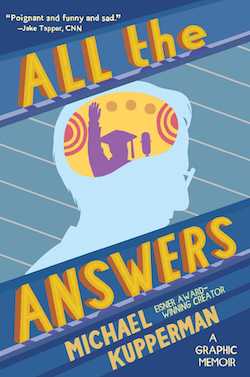

Michael Kupperman has for years been producing very funny comics for outlets including the New Yorker and McSweeney's. His work has been published in books from Fantagraphics and HarperCollins. But just when you think you've got the cartoonist figured out, he sweeps your legs out from under you: Kupperman's new memoir about his relationship with his father, All the Answers, is something special.

Decades before Michael was born, Joel Kupperman was an early television star, a quiz show celebrity whose talent — the ability to quickly and accurately perform complex math in his head — made him a beloved figure. Like most early fame, Joel's celebrity washed away. And as an adult, he refused to discuss his years as a quiz kid.

Kupperman takes great care to redefine his comics vocabulary in All the Answers. The art is very obviously still his, but the rhythm of the book is different — slower, simpler, more accessible. That's not to say that he's slumming at all: though Kupperman often only relies on two panels per page here, the relationships between those panels can be very complex.

A portrait of Henry Ford, for example, stares out at the readers from in front of a busy background that resembles TV static. The "camera" pulls back further to reveal that Ford is a portrait on a wall. The wallpaper is comprised of hundreds of thin, dense lines. Standing in front of the Ford drawing in the second panel is Adolf Hitler. It's an obvious representation of how Ford's anti-Semitism influenced world leaders like Hitler, but those clashing backgrounds also tell a thematic story about chaos and control, about personality and its influences.

Kupperman uses that kind of transition often, particularly when dealing with his relationship with Joel. The perspective in a panel will back up a step or two between panels, to illustrate the distance between Joel and Michael, and the distance between the past and the present.

As Joel ages, he grows more and more bitter about his childhood experiences. Some of that rage eventually seeps into Michael, and All the Answers feels like an attempt to harness that anger, to keep it from infecting a whole new generation.

Kupperman's self-portrait in this book is a fascinating choice: the whorls of his hair are visually appealing, and the clean bold lines of his face have an attractive curve to them. He looks friendly, except for the eyes. Kupperman draws his own eyes as tight little circles that are too small for his face. They don't wink or tense or widen. They could almost be buttons sewn on top of his eyelids, and they give him a kind of impenetrability. It's hard to emote when you don't have access to the range of emotions that a pair of expressive eyes can provide.

I think with those eyes, Kupperman is establishing a distance between himself and the reader — the same way his own father held himself back from being too emotional with his son. This could be off-putting for some readers, who might believe that the point of a memoir is to be as emotionally open as possible.

But really those immobile eyes are essential to the story: if Kupperman were as forthcoming with the reader as other confessional memoir writers, the story wouldn't make sense. Kupperman knows how to keep his audience at bay when he needs to. It creates the same aura of mystery that his father enjoyed for much of his life.

Those looking for closure will likely not enjoy All the Answers. But for everyone else — for all the people who love books about complicated relationships between parents and children, like Fun Home or The Glass Castle, All the Answers is a balm. Though it's drawn in lines so big and clear that it could practically be a coloring book, Kupperman embraces fine details and nuance in his story.

This is the kind of book that will live in your head for years. You might just find, one bleary morning after too many dreams of dead relatives, that you look in the mirror while brushing your teeth only to see Kupperman's inexpressive cartoon eyes staring back at you. Those eyes might not smile or widen, but they can see everything.