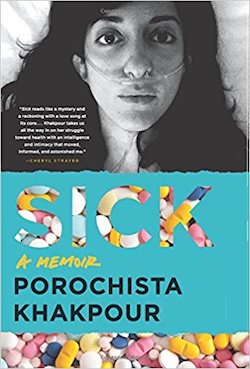

Literary Event of the Week: Sick: A Memoir reading at Elliott Bay Book Company

"I have never been comfortable in my own body," Harlem novelist Porochista Khakpour writes in the beginning of Sick, her memoir about life with Lyme disease. "Rather, I've felt my whole life that I was born in the wrong body."

This distance between mind and body, understandably, has always made Khakpour uneasy. And so in some ways, the diagnosis of Lyme disease becomes a convenient metaphor for that distance, for the discomfort she feels inside her own body. This chronic pain and lethargy and weakness at least provides a reason why she might not feel at home in her skin. A few paragraphs later, she concludes:

Because my illness at this stage has no cure, I can forever own this discomfort of the body. I can always say this was all a mistake...I have started to consider that I will never be at home, perhaps not even in death.

Sick is a book that is always bargaining with mortality. Khakpour's story of chronic pain is the story of her existence. "I have been sick my whole life," she says, and the memoir is in many ways about knowing that she'll never know what it means to have good health, that health is the Godot that will never arrive.

When her Lyme disease gets very bad, Khakpour writes cryptic emails to friends asking them to check in on her from time to time. She starts to chafe at friends telling her to "take care of [her]self." She buys a cane. She faints. She tries different drugs. She knows that she'll never recover, which forces her to readjust her understanding of what it means to treat her disease.

Few writers could pull off this kind of a memoir without making it a laundry list of despair. But Khakpour isn't a typical writer: Sick is hypnotic in its examination of bodies in the world, and all the many ways those bodies can (and do) go wrong.