Kissing Books: Romancelandia

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

Writers like to say say there are only so many basic plots in the world. (The exact number varies depending on who you ask.) It can be illuminating to consider these broad categories, imperfect though they may be. Especially when we pair them with equally broad categories of setting. Sometimes when you’re trying to trace romance taxonomy you have to step back and squint a little at the outlines.

London-set romances are frequently Person Versus Person: they turn on questions of inheritance, alliance, status, power, and secrets. Ballrooms and bedrooms figure so prominently because they’re where people come together for social and sexual intercourse — but even those rare and refreshing stories that center lower- and working-class Londoners as well as the upper crust (recent reviews of KJ Charles, Cat Sebastian, and Jude Lucens come to mind) have a distinctly societal bent. These books are about people as a super-organism, as busy and interdependent as a hive of bees in honey season. They ask how we exist in relationship to one another. Duty, honor, and obligation, all social forces, crop up like caltrops in the path of true love.

Historical romances in the American West, on the other hand, are commonly more concerned with Person Versus Environment: turning a piece of land into a town, mining precious metals, raising cattle, eradicating the natives (who are not given room to exist as People in many of these stories). We see towns and cities but as newborn ideas, sketches of the maps we know — these places are works in progress, mere gestures waving at the future inhabited by the reader. Most Westerns these days show up in inspirational romance, though there’s a stubborn, inclusive streak of queer and race-aware historicals that I for one would love to see explored more often. Especially since the environment in America is so often hostile to marginalized folks — and this can be a satisfying framework for a romance. For example: Sharon Cullars’ Gold Mountain and Backwards to Oregon by Jae, or one of Beverly Jenkins’ small town Western settings (have you read Forbidden yet??? it is perfection).

And then we turn to New York. And things get complicated.

Though there are standout historical gems to be found in this setting (Joanna Shupe, of course, and the EE Ottoman novella reviewed below) New York-set romances are largely contemporaries: the Harlequin Presents-type billionaire bent on revenging himself on his ex-business partner’s daughter, the secretly kinky CEO whose polished exterior hides a messy, wounded Dom, the sweet but ambitious heroine determined to make it in the hustle of America’s largest and most quintessentially American city. At first you might think that geography aside there’s little common ground between sweet Sarah Morgan rom-coms, the acid-tongued chick-lit trend of the 90s, and the seemingly endless wave of erotic or New Adult romances with dramatically lit covers and miles of tortured backstory — but then you look past the differences in tone, and you realize that all these arcs are very much the epitome of the plot known as Person Versus Self. It’s a story about recognizing and reconciling identities. Who are you really? Who do you want to be? There’s a Surface New York, a mythical place developed in a thousand books and films and tv shows, that presents the city as a canvas against which individual characters prove their greatness. (This is by no means limited to the romance genre: looking at you, every Great American Novelist.) The soaring, populous, silver-glass skyline becomes a mirror in which our main characters learn to better see their own outlines. Even in romances that take care to push past that shiny surface, the core arc is preserved — such as in Alyssa Cole’s A Princess in Theory, which presents us a much more nuanced glimpse into the city’s real-life demographics. Ledi and Thabiso/Jamal both have to alter their conceptions of who they essentially are before they can truly open their hearts to one another.

And of course, true to Romancelandia, as soon as we try to establish a rule we find plenty of exceptions that shatter it. This month’s books include a historical New York-set novella, a Regency that explores some of what it means to be black among the British aristocracy, a bicoastal f/f romance, a British small-town paranormal, and a Cornwall Regency miss who’s taken up smuggling for all the right reasons, naturally. Because even in romance, where setting looms large, geography is not entirely destiny.

Recent Romances:

The Craft of Love by EE Ottoman (self-published: trans m/bi f):

A trans silversmith and a heartbroken quiltmaker meet and fall in love in Gilded Age New York. They admire one another’s work and designs. They admire one another’s kindness and intellectual pursuits. The merest brush of hands makes their hearts flutter and gazes grow intense. Eventually, they confess their feelings. On paper it sounds like there’s not enough conflict to sustain even so short a story as this one. In practice, though, it’s as wildly engrossing and terrifying as the first time you look at someone and wonder: She’s so amazing—what could she possibly see in me?

Silversmith Benjamin Lewis is on the mend from a long illness, itching to get back to his smithy. While puttering about the house he discovers a cache of dresses made for him by his late mother: beautiful embroidery, but made for a person who Benjamin never truly was meant to be. But the fabric is valuable and the embroidery truly spectacular, so his sister encourages him to have the dresses turned into a quilt of some kind. She believes this could help Ben come to terms a little with his complicated feelings about his mother and their fraught relationship.

Quiltmaker Remembrance Quincy (oh, such a name!) has kept her heart guarded ever since her friend and beloved Hope abandoned her. She is drawn to Mr. Lewis’ gentle nature and warm regard — and figures out the truth of his particular identity without having to be told — but she is not sure if she wants to risk her heart again, when it was such a painful experience the first time. The two talk, and go on walks, and meet one another’s families, and their feelings blossom little by little. All while we catch glimpses of the early labor movement, Abolitionist debate, and the switch from sail power to steam. It’s a narrow window, but a lovely view.

This novella is as slender and delicate as a line of feather stitch in linen thread — and is just as quietly strong. It has the careful, deliberate kindness of voice I have come to associate with trans romances from authors like Austin Chant and RoAnn Sylver — though admittedly self-selection might be responsible for what looks like a trait of the subgenre. It’s not only that I’ve grown tired of grimdark, and misery for misery’s sake, in my fictional worlds. Reader praise of a book so often sounds like violence: we talk about our hearts being wrecked, about stories that kill us, about sadistic authors who torture and murder us as well as their characters. And that can often be quite fun! But it’s just as important to have something sweet, something kind, something healing to read when we’re sick down to our souls. This book will not hurt you. It will not tax you. This book is a warm cup of cider to soothe your aching hands, as you gently blow the steam away over the rim. Perfect for the cold days and busy holidays to come.

When she thought of him as he had been the night he’d walked her home, it made her heart quicken. There was a sweetness to him, a gentle patience that made her want to make him smile, to say clever things that would make his eyes shine. When she remembered their walk together and his visit to her workshop, she couldn’t help thinking of the movement of his strong hands, the shape of his mouth, and the long lines of his body. She wanted to see him relaxed and comfortable in shirtsleeves and with tousled hair, watch him play with his little nephew, and hear him laugh.

The Butterfly Bride by Vanessa Riley (Entangled: historical m/f):

To read Vanessa Riley is to feel the drape of lace against your wrists, as the rich scent of antique perfume fills the air. It’s transportive, is what I’m saying, over and above the usual. It’s a rare author who can write books that feel properly vintage without being stuffy, and it was terribly easy to lose myself in the author’s poetic, crystalline cadences.

Miss Frederica Burghley is the biracial bastard daughter of a notorious courtesan and a duke; she is illegitimate but acknowledged, a privileged but precarious position. Jasper is Viscount Hartwell, a widower still devastated by the loss of his beloved first wife, and burdened by three unruly daughters who are the terror of their many governesses. Jasper and Frederica wake up in bed together, fuzzy-headed, the day after Frederica’s father’s wedding. They have no memory of how they wound up there — except Frederica’s horrified recollection of bits and pieces of the night before: a hand breaking through her window, a whispered threat, a stolen jewel-box, and the ruins of a wardrobe viciously slashed to pieces. The duke and his new duchess will not put off their honeymoon, so the duke asks Hartwell to protect his daughter while he’s gone. Meanwhile Frederica plans to get herself quickly and properly married so the possessive thief will stop threatening her dearest friends and relations. Hartwell thinks this is a terrible idea — he’s not wrong. Frederica thinks Hartwell’s still too much in love with his first wife to give his heart easily — she’s right. There are weddings and suitors and a lot of meaningful piano playing, and (small content note) an emphasis on the dangers of historical childbirth that is both stark and refreshing in a genre that so often presents pregnancy as a wondrous miracle and gift, rather than the hugely risky undertaking it was in the days before ultrasounds, antibiotics, and regular hand-washing.

So yes, this book has a lot going on — but it feels deliberately layered, baroque rather than busy. And a soupçon of Grand Guignol at the end, to make the reader’s heart lurch with fear. This is the kind of romance plot where people stick stubbornly to painful decisions even after their hearts have realized the anguished truth; you kind of want to shake them, but in a good way. I was frequently reduced to keeling over on the couch and yelling argh out of sheer enjoyable frustration. Frederica in particular is a heartbreaker: lonely and fiercely brilliant but unsure of her place in the world, thanks to a rather unfeeling father and an awareness of how thin the ice she skates on truly is. She deserves every care and attention and it was a delight watching Hartwell slowly come to the same conclusion. This is surely a book to savor with a glass of fine brandy and a snowy window view; and how decadent that there are two prior books in the series for when you happily sigh and set this one aside!

Their gazes locked. He was on his knees, her hand pressed to his. If the carriage stopped, people would get the wrong idea. The question was, would he care?

Mating the Huntress by Talia Hibbert (self-published: paranormal m/f):

It’s the spooky season! I have to review at least one paranormal! But I am extremely picky about my paranormals, especially where shifters and fated mate tropes are concerned. Thankfully, Talia Hibbert (with whom I now share an agent, full disclosure) surprised us with a silly, sexy little paranormal and as always it’s a damn delight.

Luke is a Werewolf. A slavering, ravening monster, designed to prowl the night and tear the throats out of unwary humans. He’s strong. He’s fast. He’s nearly impossible to kill. Any reasonable woman would run screaming rather than follow him back to his cabin in the middle of a dark and lonely wood. But Chastity Adorno is no ordinary woman. She’s a huntress — well, she would be, if her family would let her join them on their killing nights. Something about a prophecy at her birth has left them a little overprotective. It grates on her nerves. So when a Werewolf starts showing up at her coffee shop, looking all human and sexy and shy despite being a monster, she thinks it’s her chance to finally get a kill and take her proper place among her sisters. She agrees to a date, and straps a silver dagger to her thigh.

Any romance reader steeples her fingers at this point and waits for it all to go beautifully, wonderfully wrong.

Paranormal romances trade in power metaphors — so most of the time most of the power ends up with the hero. (At least in het romances: I don’t have a strong sense yet of similar patterns in queer romance. But I’m working on it!) He’s often rich and immortal as well as super-strong both physically and magically. But I find I’m happier with paranormals that Take care to even the scales: Isabel Cooper’s dragons (both heroes and heroines), Shelly Laurenston’s alpha shifter heroines (just as murderous and horny as the dudes, and so fucking funny), and Alisha Rai’s witty, wicked Persephone retelling Hot as Hades. And we can definitely add Mating the Huntress to the list, because our huge, lurking, slavering, unkillable Were is almost instantly revealed to also be a comforting, attentive, eager-to-please bundle of joy. Who loves how tough and grumpy and violent the heroine is. There’s a particular type of hero I’ve come to call the Sex Puppy: hot, cheerful, usually funny but not too bright, and absolutely here for the heroine’s pleasure and happiness, exactly as she wants it, no more, no less. It’s a fun, comforting archetype, and this Werewolf is the Sex Puppiest shifter of them all. This book is a piece of pure paranormal candy, and I for one am here for any other glimpses into this world.

Christ, she wasn’t shy at all, was she? The hesitation, the demure smiles and lowered lashes — it had all been a trap. She wasn’t sweet or gentle or biddable. She was a bloodthirsty fucking murderer.

His heart sang.

Off Limits by Vanessa North (self-published: bi f/pan f):

I can scoff about Romancelandia dukes and billionaires all day, but you wave a half-glam, half-punk queer romance at me and all my capitalist criticisms go right out the window. Charity balls, sweaty concerts in dive bars, Hollywood celebrity exes, a glitzy and gay New York: I was totally in. This book is the first of a multi-author series set in two high-class queer women’s clubs: the Thorns in New York, and the Rose in LA. It’s stylish and sexy and sharp as all hell. I positively reveled in it.

Natalie is both a buttoned-up concierge for the Thorns and, as Nat, the lead singer of a sexy, angry, queer-as-hell punk band with a standing gig at a pub called the Bridgewater. Rebecca Horvath is a trust-fund kid, the child of Hollywood royalty — and, as a club member at Thorns, completely off-limits for Nat. (Hey, that’s the book title!) But sizzling chemistry, a criminal scheme, and Bex’s dad’s rush wedding conspire to throw them together over and over, and it’s no surprise when they give in and tumble into bed together. Nat is all edges and anxiety beneath her mask of control, and Bex is delicate as spun glass beneath her rich-girl polish, so their romance is less of a climb and more of a roller coaster as they try to find their footing in a world that honestly feels like near-chaos at all times. It left me breathless. The plot is full-throttle drama, every scene risking something or tightening a different piece of the tension — strong content note for a secondary character’s fairly intense suicide attempt — and I absolutely burned through the pages before I knew it. My one quibble is that after all the agony, the ending felt just a shade too easy. If you’ve enjoyed Anna Zabo’s queer rock romances, this is for sure the next thing you’ll want to pick up.

At the club, she’s invisible. On stage, she’s a giant. At home — mine or hers — she’s the light in every room and the warmth in the radiators. Without her, the bed is cold and the rooms are lonely, and I feel the weight of her uncle’s disapproval every time I glance at the photos on the walls.

This Month’s Historical Heroine Who Resorts to Smuggling for All the Noblest Reasons, Obviously:

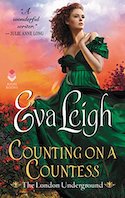

Counting on a Countess by Eva Leigh (Avon Books: historical m/f):

I am shamefully behind in my collection of Eva Leigh books, but I buy every one as soon as I can because I’ve been reading her for a decade and there’s just something about the way she structures her plots that slips under my skin and gets my mental wheels turning every time. Continuing the trend, Counting on a Countess is a romantic meditation on the relationship between any individual and the state’s legal code. In particular, this romance uses the weight and weirdness of British law to anchor a fictive argument about the difference between laws-as-rules, and laws-as-social-obligations. Like my current favorite sitcom The Good Place, this book asks what we owe to each other while taking a blunt, critical look at a legal system that is both unyieldingly powerful and cruelly capricious.

We first meet our hero, Waterloo veteran and newly minted earl Kit Ellingsworth, cheerfully drunk and about to bang two — yup, two! — very willing opera-dancers. Kit has vague plans of building a pleasure-garden to chase away the shadowy memories of war, so he is first elated and then appalled to learn he will inherit his late commander’s fortune — but only if he marries within the next thirty days. At once we shift to our heroine Tamsyn Pearce, a bold Cornish smuggler who‘s wondering whether or not her new fence might want to kill her. Tamsyn took up smuggling to help her struggling hometown survive in the harsh economy of the Napoleonic Wars — but now her jerk uncle is planning to sell the manor house where they hide the French lace and brandy, and all her usual partners have bowed out for fear of discovery. She’s come to London to try and find a new buyer for the latest shipment, but when she’s turned down yet again she comes up with a new plan: she’ll marry a man with money.

Both Kit and Tamsyn have run afoul of the law, but with different intentions and with vastly different stakes. Kit is dismayed by the conditions of the will but the money is not a matter of life or death for him. Tamsyn, on the other hand, is fighting to keep her townsfolk from starving: the fishing hauls have been terrible and the post-war taxes burdensome. She fears being killed by the criminals she works with, but also knows that the law does not ensure her survival. This profound mismatch between Kit and Tamsyn creates friction, which keeps the plot engine turning — especially once the lawyers reveal a codicil to the will that makes all Kit’s financial decisions subject to Tamsyn’s approval. Which of course is something a wife is expected to endure, but which as a husband Kit finds deeply unjust, so now we have another layer poking at the relationship between doing what’s lawful and doing what’s right. It gave my brain plenty of fodder for analysis, just when I needed it. There are a few quibbles I had with the book by the end, but listing those would feel like pointing out that you don’t really like the floral print on this amazingly well-sprung and comfortable armchair. Sometimes a well-designed structure trumps everything.

“I’m … more wild than tame. If I had to choose between a ballroom and the prow of a fishing boat, I’d take the fishing boat every time.”

And because the author name-checked Penzance once and my brain took the reference and ran with it:

Kit is the very model of a romance hero veteran

He wants to build a pleasure garden that he can feel better in

He has to marry quickly to ensure financial solvency

But debutantes are wary of his rampant alcoholency.

Our Tamsyn is a country girl who cares about her neighborhood

She knows that smuggling earns her more than honest, legal labor would

She needs to buy a manor house to hide her lace and brandy in

Which leaves her little left to spend on Kit’s unending dandyin’

They marry for the money but that’s not the only thing they spend

There’s quite a lot of angsty plot before they reach the happy end

In short when he decides that love there’s really nothing better than

Kit is the very model of a romance hero veteran.