This report was written by Paul Constant and Dawn McCarra Bass.

The Short Run Comix & Arts Festival on Saturday felt just as busy as ever, but it didn’t quite feel as crowded as the most recent iterations of the festival. It took us a couple times around the floor to figure out that there was one fewer row of artist tables in Fisher Pavilion, which created an easier flow throughout. No more smashing into some random person’s backpack when you turn to check out an especially enticing comic on someone’s table! No more stuttering steps necessary as you chug behind a small army of slow-walking looky-loos!

From a visitor’s perspective, Short Run was as smoothly run and as packed with intriguing new titles as ever. The show has grown nicely into Fisher Pavilion — so much so that it’s hard to remember when it was held at Washington Hall or in the Vera Project. Short Run is home, and the festival reached a point in its development when most people involved know what to expect. “Short Run” has become a shorthand for a very particular aesthetic: supportive, enthusiastic, eager for new work and new talent and new artistic perspectives. It’s becoming an institution of its own. Here’s what the institution meant to us this year:

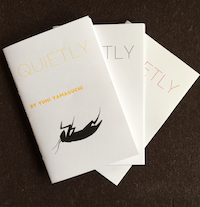

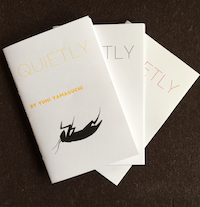

It was the covers of

Yumi Yamaguchi’s Quietly that sucked us in: they’re simple, even plain, but color-saturated text against stark white paper and inkpool illustrations gives them a collect-‘em-all quality that’s irresistible. So are the stories inside. We picked up issues three, four, and six, which chronicle the daily trials of Maud, a librarian, and her colleagues. Maud flips between quiet evenings at home with a book and her cat and long days dealing with the astonishing entitlement of library patrons: patrons who bring in buckets of aromatic fried chicken, talk loudly on the phone, watch porn, ruin books … and the patrons who complain about them all. The pacing, the paneling, and the casually detailed illustration perfectly evoke how everyday annoyances can be both blandly repetitive and as uncomfortable as a splinter in the eye. You’ll enjoy all of it. Then you’ll get the end of

Metamorphosis, the first in the series, and a sudden turn (which we won’t spoil any more than this) will make you cackle with delight. The other issues of

Quietly are semi-autobiographical, and not buying the full suite so we can read them right now is one of our #shortrunregrets.

Not unlike

Quietly, we fell in love with

Grace Helmer’s

Legs Up! from across the room. The bright colors and positively Clowes-ian figures of the UK artist’s gynecologically minded memoir comic look unlike many of the other Short Run artists around her. Helmer’s art looks almost as though it’s composed of delicately cut layers of colored paper; there are very few actual inked lines on the page, giving the emotions and energy of her comics a warm, vivid feel. Even the way Helmer draws a toilet full of blood feels approachable. It’s the perfect style for a bracingly honest confessional comic about intimate details from the artist’s life. Helmer is

raising funds for a new autobiographical comic about Tinder and death, and fans of comic memoirs should consider supporting her. These are important and raw stories, told beautifully.

Katherine Quartermane, do you exist? We bought a zine from you, but the internet yields no evidence of you beyond the book sitting next to us now, barely larger than the palms of our hands.

Your Hands o Mis Manos is beautiful and wry and mysterious, Katherine; we love the which-way-is-up collages, the disorienting shifts in type size and setting. We love how the Spanish text dominates and dances over these pages, and how the English sits quietly offsides, as transparent as a good translator should be. We love the brevity of this little zine, and how much it says in just a few pages. We love laughing at “why does saying jalapeños incorrect seem funny?”, and that you laughed with us, and we love waking up to the protest in it (“my culture is hanging by a thread”). We love the inclusion of ways to support immigrant rights, especially this week, but especially every week. We hope we see more of your work at another festival soon.

If you grew up reading the short jokey comics of the 1990s — think Evan Dorkin, early

Eightball, and the work of Ivan Brunetti — you’ll want to get your hands on

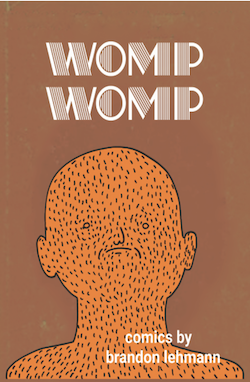

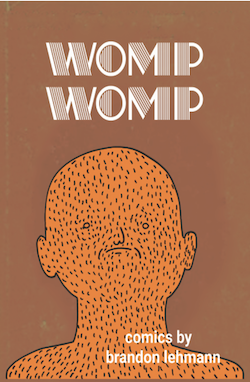

Brandon Lehmann’s

Womp Womp. It’s a one-cartoonist anthology full of jokes (never trust a cartoonist who’s too proud to end on the word “pooper” as a punchline) and experimentations in style and timing that combine to form more than the sum of their parts. Topics discussed in

Womp Womp include god, flip phones, cats, and butts. Lehmann is comfortable exploring the concept of free will in a two-page gag strip, and he’s happy to end that theological examination with a fart joke. That’s pretty much the cartooning dream, right there.

“I want my body to feel more right for me and I want to be gendered correctly … And I want to be head-turningly hot.” That’s the brilliant

Kayla Rosen, launching into

T&A (

Transitioning and Attractiveness), a sharp, funny, and poignant zine-shaped essay about the medical transition of their body to better match their nonbinary gender. Rosen tugs at a dizzying number of threads — the awfulness of evolutionary psychology; the myriad uncertainties of transitioning; how any human knows whether he or she or they is desirable (or, let’s just say it, fuckable), especially when they’re intentionally steering outside the norm. Their writing is intellectual, political, no holds barred, but also personal, frank, and self-aware. It’s an enviable bit of sleight of hand and a real gift to the reader, given the complexity of the issues they raise. And

T&A is a real gift, too, a stake in the ground against the atrocity of Donald Trump’s attempt to define away the humanity of the trans community.

When

we talked to Short Run chair Mita Mahato last week, she warned us that her latest book,

Lullaby, was possibly the saddest thing she’d ever made. She was not lying.

Lullaby is a spiritual successor to one of Mahato’s best comics,

Sea. Like

Sea,

Lullaby is produced using Mahato’s signature cut-paper cartooning style. And like

Sea, it takes place in the oceans. But while her last book told the story of the beauty and grandeur and the hugeness of the sea,

Lullaby is focused on what humanity is doing to the seas: we’re making them smaller and crowded and filthy.

Lullaby is a keening cry for a year whose local news cycles revolved around a dead baby orca whale and whose global news cycles were led by promises of an ecological apocalypse arriving decades earlier than previously promised. Make no mistake:

Lullaby is a beautiful book. But the rusty reds and sickly greens of this book, and the claustrophobic paper-cut waves circling in on the family of orcas, are intended to make the reader sad.

Lullaby is a remarkable work of empathy, and perhaps Mahato’s strongest book yet.

Hey, being an ally is super hard, nobody’s saying it isn’t. Here’s some good news if you’re white, cis, male, or (god forbid) all three: there’s a new volume of Shana T. Bryant’s destined-to-be-a-classic Terrible Allies: Vol. 2: Still Terrible. Bryant is exceptionally good at skewering the haplessness of privilege, and in the small universe of these comics (usually two to three characters at most), she shows us exactly how bad good intentions can be. She’s also a genius at capturing mood in just a few lines. Some of our favorite sequences repeat images with subtle changes to the shading and focus that deliver endless varieties of clueless self-consideration.

This is a perfect example of the many, many things comics do well: it’s not easy to hold up a mirror in a way that’s palatable enough to be effective, but Bryant uses the form to build empathy and force perspective the way she wants it. Bryant works in tech in Seattle, so it’s a miracle she draws with as much gracious humor as she does — but it’s because her characters are both gracious and unyielding that the book gets its message through. In our brief time at her table, we chatted about her customers’ fear of finding themselves in the pages: As Bryant said, a lot of people pick up her books with a wince; nobody wants to recognize themselves as the bad guy. But that’s the only way to get better. And just a reminder: “Real allies vote. In every election. (Even the boring ones.)” Vote!

Friends, have we talked before about how Greg Stump is one of Seattle’s best cartoonists? It struck us reading Blockhead, the collection of the last five years of Stump’s short works, that we maybe don’t praise him often enough. Here are strips covering a wide range of topics — a memoir strip about an eleven-year-old Stump trying to hustle a contributor copy of Hustler by submitting a “cartoon about prostitution and venereal disease” to the pornographic magazine; a story of a ghost who just wants to go bowling; reviews of author readings at Seattle Arts & Lectures events; a monologue from God about how He is jealous of Santa Claus. Stump makes it all look so effortless that it’s easy to forget how much craftsmanship goes into every single panel.

We open

Toast — story by

Kate Berwanger, text by

Amelia Fawn. Bagged in cellophane, the tiny book is water-wrinkled and bulging, and dirt, then leaves, then — a twig? yes, a twig — fall onto the floor. We smell dust and burning, the smell of late summer in the midwest, the smell of places where nobody has time or money to spend on lawns and landscaping, of children make-believing their boredom away in abandoned lots and stunted rural woods. The nameless child who lives here has a vast empathy that extends to toasters and spoons, to barns and screen doors, to abandoned toys and broken mirrors. Her parents have forgotten she’s a child. She takes the brunt of their misery and frustration. Nothing happens in Berwanger’s story, except a childish wander and a rising understanding. Nothing happens in Fawn’s illustrations, except the immediacy of what the child sees: a bent spoon, a rabbit, a doghouse labeled “Shithead.” The dirt is from Ohio, which is where the non-story happens. We assume the twigs are too. We tuck them back between the pages, gently. Berwanger and Fawn have made something that tugs on memories most children share, to share memories we’d rather not. It’s an incredibly well-played hand.

Every Short Run, we ask the more established cartoonists a single question: Who have you seen at this show who is new and local and wildly promising? This year, young Seattle cartoonist Lauren Armstrong was the name most often mentioned. Her comics don’t look like traditional comics — ”it feels like she’s coming from outside the medium,” someone told us, quickly adding “in a good way” — which makes Armstrong an outsider in a field of outsiders. Armstrong had several “books” at Short Run that were simply one big comics page, folded down to a tiny little square package. Penis is the story of a skateboarding accident that severs a skater’s penis down to a bloody stub. While doctors try to reattach the severed penis “with modern medicine,” the anthropomorphized stub decides that it doesn’t miss the penis at all. (Its first words: “FRESH AIR…”) It’s an intentionally ugly strip, but all the people who sent us Armstrong’s way were right. These comics feel like they’re from an alternative universe, one where comics never got sidetracked with superheroes and instead were co-opted by fine art instead. We can’t wait to see more of Armstrong’s work in the near future.

We’ll have plenty more reviews of Short Run books in days to come on this site. But what no laundry list of Short Run hauls can convey is the feeling of what it’s like to be in the room. When you’re part of the bustling crowd, seeing familiar faces and looking out for exciting new art, Short Run feels like the most hopeful place on earth. You just know that if you look hard enough, you can find a good friend you haven’t seen in months. And you also know that if you cast your eyes far enough from one wall to the other, you’ll see a kind of artistic expression that you’ve never before imagined.

Aside from all the talk about politics — seriously: vote, okay? — and all the concern for Seattle as an increasingly expensive place that no longer welcomes artists, the individuals we talked with were personally hopeful. Marc Palm was still riding high from a recent gun responsibility comic going viral, and he was eager to produce more work for Mad magazine and other outlets. The publishers of Thick as Thieves were looking forward to producing a new issue in early 2019 that they hoped would usher in a new era for the magazine. Short Run co-founders Eroyn Franklin and Kelly Froh both had new work at the show that demonstrated their continuing affection and curiosity for the artfrom. People were hard at work planning new projects, scheming together about possible events, and scheduling times to get together and talk about how to turn comics on its ear.

No matter what kind of political conflagration is happening around Short Run, the happy fact is that Short Run remains the same. This is not a show that will break your heart. This is a show that will welcome you and reward your patience and remind you why you fell in love with art in the first place. You leave Short Run ready for the year to come.