Thursday Comics Hangover: Los Angeles, city of animation

Natalie Nourigat's comic I Moved to Los Angeles to Work in Animation is exactly what it says in the title: it's the story of what happened to Nourigat when she moved to LA to pursue a career in animation.

If you asked me to quantify it, I'd define the book as about 30 percent memoir and 70 percent a career how-to guide. Nourigat withholds a lot of personal details (don't expect relationship drama here) in exchange for broad strokes about what it means to be young and in animation.

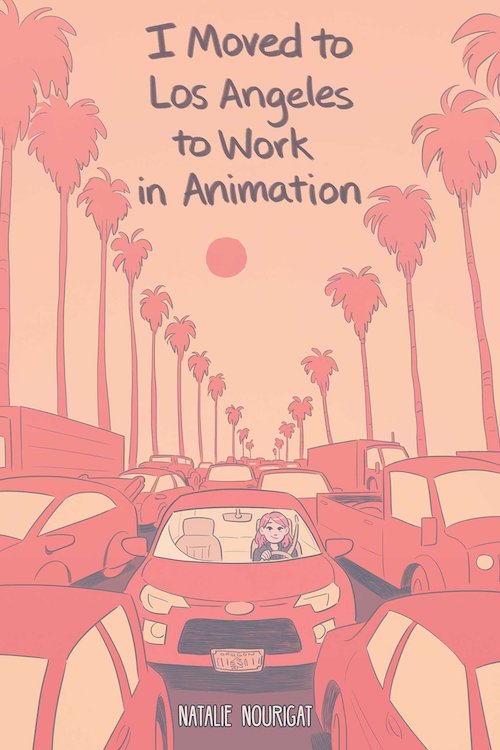

This is practical information, delivered by a pragmatic (but cheerful!) guide. The fact that the cover of the book features Nourigat in her car sitting in traffic on an LA highway should offer some context about what to expect: she gets into the nitty-gritty of moving to LA, even specifying that many Los Angeles apartments don't come with refrigerators.

Perhaps aspiring animators might feel let down that so much of the book concerns itself with the details of life in Los Angeles, but the truth is that geography is still a vital component of show business. Even if you're the next Walt Disney, you're never going to get a job working in the story department of a Netflix animated show if you refuse to move out of St. Louis.

And the fact is that geography has impacts on art, too. Consider this passage:

I miss walking a lot. I daydream about walking cities all of the time. And I miss drawing people walking. I barely sketch from life anymore. It's hard to find a good cafe with seating and a view of foot traffic like I'm used to in other big cities. LA is just not a pedestrian city, and people-watching spots are few and far between.

Where you live impacts your art: both what you draw and how you draw it. Would movies have as many car chases if they were made in a city with a walking culture? Would animation look more naturalistic and human-scaled if animators walked to work every morning?

Even for someone who never once considered a career in animation, Los Angeles is an interesting comic. Nourigat is a gorgeous illustrator — in just a few lines, she can render a complete sensation of a whole city, or a panicked expression, or a workstation at a Hollywood studio. The vibrancy of her line calls to mind great cartoonists like Jack Cole.

Unfortunately, the comics part is a little less impressive. This book demands a lot of text, and the balance between words and pictures is more than a little lopsided. (The last section of the book especially, which features interviews with animators, is basically walls of text hanging over tiny sketches of faces. These interviews are interesting and valuable, but they're very bad comics.)

But not every comic needs to be a masterpiece of synergy between words and pictures. Explanatory texts like this one can be more wordy and essay-like. There is not enough money in the world to pay me to read a full-length prose book about breaking into the animation industry. Nourigat's comic on the same subject, though, not only won me over, but it entertained me the whole time.