Thursday Comics Hangover: Comics are for kids!

One of the most confusing aspects of modern superhero comics is the way children are treated by the industry. Both of the big two publishers frequently publish a separate line of superhero comics for kids with cartoony illustrations and simplified stories that are done in one issue. They look more like Saturday morning cartoons than something you'd find in a standard superhero comic.

The thing I don't get about this strategy is this: like most people my age, I started reading superhero comics as a kid by diving into the same serialized comics that adults read. I started reading in the middle of storylines and would figure out what was happening as the storyline unfolded.

As good as these modern superhero comics for kids are — Art Baltazar is a seriously underrated talent — I wouldn't have touched them as a child, expressly because they looked like kids' stuff. The superhero comics I read as a kid (Byrne and Claremont's X-Men run, the Justice League of the late 70s, anything with Spider-Man in it) were interesting to me because they felt more grown-up.

However, I wouldn't give a modern superhero comic to a young kid now without reading it first. Too many titles are filled with faux-mature "shocking" violence to just blindly hand a book over to an 8-year-old. Perhaps that bad emulation of Frank Miller and Alan Moore's 1980s grittiness is what created the cartoony kids lines in the first place: as a safe space for children, to protect them from the generation that refused to give up superhero comics and demanded that the heroes mature with them.

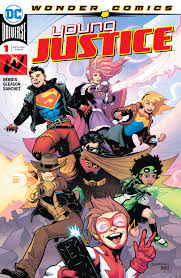

Yesterday, DC Comics published the first issue of Portland writer Brian Michael Bendis's Wonder Comics imprint, and the genius of it is that it's a book you can hand anyone, young or old. Originally published in the 1990s, Young Justice was a team of superhero sidekicks — Robin, Superboy, Wonder Girl, the junior Flash known as Impulse — that was swept aside in some reboot or another. Alongside artist Patrick Gleason, Bendis has revived the team with a few new characters including a descendent of Jonah Hex and a hacker riff on Green Lantern.

Young Justice #1 doesn't dilute its superheroic pleasures for young readers. It drops you in the middle of DC Comics's complex continuity without much explanation, and it starts the action almost immediately. Bendis reveals just enough about each character as they're introduced to the story that new readers won't get lost. If they're intrigued, those readers can then read backwards into DC Comics history to learn about any of the characters or concepts in the book.

Honestly, the story in Young Justice #1 is pretty slight — hero team assembles in the face of an interdimensional invasion — but that's by design: it leaves plenty of room for a kinetic and inventive superhero action sequence by Gleason. And Bendis adds lots of little touches along the edges of the story to reward longtime readers of DC Comics. (The citizens of Metropolis are almost blasé about the invasion, moaning about the fact that they'll have to fill out another insurance form.)

It's possible that Young Justice might fall apart in any of the myriad ways that superhero comics do — artists can be late, stories can stretch out too long – but as far as first issues go, Young Justice #1 is a note-perfect example of how to make superhero comics for readers of all ages.