The Future Alternative Past: In praise of assholes

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Later this month I’ll be teaching a bunch of writing students about depicting the best of all possible villains. It was a request. I never would have come up with such a topic on my own, because I don’t usually think in terms of heroes and villains. Too binary for me. But if I have to talk about them I will, and I’ll start by ruminating publicly on the matter here. My thesis: a good villain is as moving as any hero.

My favorite villain in SFFH, a robust, righteous example of the type, is the Baroness Ceaucescu, who appears in Paul Park’s Roumania Quartet. She’s mad, of course, from the perspective of readers and the book’s other characters. From her own perspective, though, she’s doing the best she can to make the world a better place. From her own perspective she is her nation’s savior, the legendary “White Tyger” who will throw off this alternate Eastern Europe’s German oppressors and lead her people to freedom. From the perspective of the Baroness Ceaucescu, the book’s heroine Miranda is an annoyingly impertinent teenager with no appreciation for the opera the Baroness is composing or, indeed, for anything that truly matters.

Perspective is often key when it comes to portraying villainy. Since very few see themselves as evil, it’s up to the author to show us how utterly inadequate the baddies’ self-assessment skills are. I wrote my short “Everfair adjacent” horror story “Vulcanization” from the viewpoint of its villain: Belgium’s King Leopold II, a man who perpetrated one of the worst human rights disasters in history. Leopold is Everfair’s villain, too, but in the novel I give him zero screen time. In this short story’s briefer stretch I was able to stay inside my bad guy’s head all the way to the finish. I stuck it out for 25 double-spaced pages, contrasting Leopold’s reprehensible actions with his internal justifications for them — which justifications include his handsomeness and horniness.

Not every villain is wrong about being right, though. The moral relativity of Kameron Hurley’s assassin Nyx, heroine of her Bel Dame Apocrypha series, helps establish her opponents’ positions as entirely tenable. And in Richard Morgan’s latest novel, Thin Air, Madison Madekwe’s completely understandable motivations render her more than the mere recipient of antihero Hakan Veil’s lust-fogged suspicion. She works for what she wants, with good reason.

Does she get it? The problem with answering that is the problem with mentioning Madekwe at all in this context: spoilerage.

And so we will pass quickly from the particular to the general. Or the genre-al.Who lives their life expecting to fuck things up for a good guy? Who delights in evil? Who rolls in it like a dog rolls in vomit? Horror is where you find these sorts of villains. The vengeful baka in Tananarive Due’s The Good House, for instance, knows itself for what it is, and revels in that knowledge.

Horror is also home to HP Lovecraft’s cyclopean amorality, the cosmic indifference of the Old Ones. By their very nature inimical to humanity, Cthulhu and Co. never attempt to justify the terrors created by their mere existence. Which is all very well, since our intellects are too limited to understand them. Stripped of even the thinnest of rationalizations, this is villainy at its purest: isolated, self-sufficient, orthogonal to all conceivable good. Pure, yes, but I still prefer my dear Baroness. And that is why I’ll advise my class to temper their villains with a touch of virtue — so readers will be able to relate to their misdeeds more easily, more sadly. More truly. More movingly.

Recent books recently read

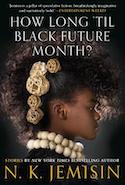

The answer to the title of New York Times Bestselling novelist NK Jemisin’s new book, How Long ‘Til Black Future Month? (Orbit) is “No time at all.” Black Future Month is now and always. Or at least it can be. Read this collection of fiercely imaginative short stories to see how triple Hugo Award-winner Jemisin envisions android recruiting agents and the heat-death of social networking, how she responds to Ursula K Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” in “The Ones Who Stay and Fight,” and to Robert A. Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters in “Walking Awake.” Black and brown characters abound. Going beyond that remedy to one-sidedness, though, Jemisin makes visible — makes palpable — the difference in parallax arising from black cultural experiences. That means sensawunda squared for those from other communities, and well-grounded vaultings beyond our accustomed skies for any who share her African and African American roots. Fresh assumptions about who survives the end of the world and who gets to explore space frame “Cloud Dragon Skies,” “The Evaluators,” and pretty much every other story in this valuably insightful book. For further reading there’s the book’s title essay, which references Janelle Monae and The Jetsons. It prescribes joy and curiosity and thoughtfulness as cures to the bleakness of imagining non-inclusive futures.

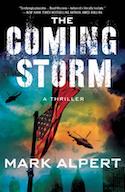

The Coming Storm (St. Martin’s Press), the fourth novel from Scientific American contributor Mark Alpert, pits a new branch of the U.S. military against New York City. Various Gothamites such as gangbanger Hector Torres and out-of-work geneticist Jenna Khan survive back-to-back superstorms while maneuvering against scheming Federal officials and a demented President. Set in 2023, Storm realistically depicts a world ravaged by climate change; its characters represent a full spectrum of NYC-style diversity, too. But Alpert’s wild extrapolations from the current state of CRISPR technology lack plausibility. And his villains, while admirably self-involved and self-righteous, are universally, devotedly, one-dimensionally evil. Not credibly complicated. Not my favorites. They’re targets for anger, but they are still ones. Not moving.

Couple of upcoming cons

Boskone 56 bills itself as New England’s oldest science fiction convention. In addition to this year’s official guests — authors Liz Hand, Vandana Singh, Cindy Pon, and Christopher Golden, artist Jim Burns, and my favorite deceased editor, Gardner Dozois — there are sure to be a bunch of other smart, fun, cool people attending along with you.

So what’s New England’s newest science fiction convention? Depending on how you define your terms — are video games and anime SFFH? Is Nebraska in New England? — it may be Kanpai!Con. In Japanese “Kanpai!” means “Cheers!” Japanese culture’s kind of central to this con’s identity. Official guests are mostly voice actors I’m personally unfamiliar with, me being old and out of the loop. But if you’re a bit more clueful you’ll probably find lots of exciting info on the site linked above.