Kissing Books: Whiteness, amnesia, and the uses of historical accuracy

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

We talk a lot about historical accuracy in our commercial fiction. I would like to talk a little bit about accuracy in our history of commercial fiction.

Let me take you through a case study.

Back in that dimly remembered epoch known as The Year 2015, author Stephanie Dray made a racist joke while finishing a novel about Thomas Jefferson’s eldest daughter. Screenshots were passed around; many people spoke up about how harmful this was; Dray and her co-author Laura Kamoie (who also writes as Laura Kaye) apologized, saying their book about a wealthy white woman was really meant to illuminate the evils of slavery, and kept their heads down long enough for the conversation to move on.

Then in April of 2018 they came out with a novel centered on Eliza Schuyler Hamilton. It is obviously, explicitly riding along on the musical’s wave of popularity. I have read and enjoyed Hamilton-inspired romance before; unfortunately Dray and Kamoie’s take ignores the modern musical’s revolutionary casting to focus primarily on white historical hottie Alexander Hamilton. They seem to mistake the musical’s subject (A. Ham) for the message (immigrants make valuable contributions to the American story).

Hamilton the musical boldly put black and brown faces center stage at America’s foundational moment; My Dear Hamilton reaches out for that bright spotlight and turns it once again on white people. The novel is historically accurate, because Alexander Hamilton was indeed a white man—but the change of focus feels like an erasure because it casts aside the present-day interpretations of the historical figure, where kids singing about Hamilton, Washington, and Jefferson are envisioning them as Puerto Rican and black.

This is the equivalent of answering: “It’s whom, actually” when someone asks you: “Who did you shoot in that duel?” Technically correct, but missing the greater point of the question.

While promoting the Hamilton book this winter on Facebook, Dray shared a post from the Historical Fiction Authors Co-op, highlighting a brand-new novel about black performer Josephine Baker by white author Sherry Jones.

So now, if you’re keeping count, that’s two novels by white authors capitalizing on the historic success of black/brown artists, taking advantage of the same promotional network to boost their books’ visibility and sales.

Still with me? There’s more.

If the second author’s name sounds familiar, maybe it’s because you remember that back in Ye Olde 2009 Sherry Jones’ novel about Aisha, The Jewel of Medina, was at the center of an intense literary scandal for its treatment of Islamic religious history as escapist entertainment. Rather than trying to untangle the whole discourse about Orientalism, Islamophobia, censorship, and the West, let us look at the novel’s starting point: according to an interview from this past November, Jones was “inspired by an essay she heard on NPR shortly after 9/11 about a Muslim woman who renounced her faith due to Islamic extremism and the misogyny that comes with it.”

She heard a Western news outlet’s edited version of a contemporary Muslim woman’s experience, in the confused aftermath of a generation-defining act of violence, and chose to write a novel exploring, well, a Western white woman’s interpretation of Islamic history. According to an interview from Patheos in 2008: “I did all this in the service of what I see as a truth. My truth – this is my vision of what things would have been like based on my own experiences and my own research and my own intuition and observations of human nature.”

Jewel of Medina caused the kind of shitstorm you’d think would be a career-ender. Instead, Sherry Jones is now with Simon and Schuster. Her Josephine Baker book is getting enough buzz that I noticed it way over here in my happy romance bubble. The glowing Kirkus review says Jones’ new novel “offers a corrective to some of Baker’s own fabrications about her life.”

Just as a suggestion, if you decide you must dismantle the defiant self-mythologizing of a cherished and complex black celebrity in the name of pedantic historical trivia, please at least get anyone but a white novelist to do it. Next thing you’ll be informing me Queen Bey has not in fact been legally crowned as the head of any existing monarchy. Again: this approach is technically correct, but pedantically narrow.

On Facebook, Jones complained about “so-called ‘reviewers’” who were disappointed to see what she’d left out of Baker’s story. She stated they were “missing the pojnt [sic] of the book.” In comments she continued: “We couldn’t possibly write every detail of our subjects’ lives; nor would we want to.” This is a painful truth about writing historical novels: at some point, you’re going to have to either leave something out, or make something up. The historical record is full of gaps, it doesn’t always line up in a neat narrative, and every author has to find a way to come to terms with this. And you could hand the same biographical facts to three different authors and get three wildly different novels. Such as, say, Alexander Hamilton.

But an author should be comfortable having those gaps pointed out, since these are decisions you ought to have at least a minimum justification for. The historical record does not belong to you alone. Creative works do inform our understanding of the past—especially if they’re bestsellers and supported by marketing dollars. If Josephine Baker isn’t just a historical person anymore, if she’s also the main character in a popular novel, then who we think she was depends on the author’s approach to the facts.

Deciding what to emphasize, what to alter and what to leave out of a historical account gives an author a great deal of power—especially if the person you’re writing about is dead and can’t argue back.

For modern novelists, the promo grind is endless. It’s a crowded market, with a vanishing midlist, and we’re all fighting for every scrap of reader attention. We are encouraged to seize opportunities, to play up connection points between our work and current trends and events. It’s why bookstores put up displays full of material on Hamilton and Burr; it’s why I took photos of me holding up my favorite astronaut romances that time I visited NASA. That constant pulse of scrambling for relevance might explain this shareable public post from Sherry Jones’ Facebook page, where she makes time to point out on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day that “Josephine Baker used her platform to demand equality years before Dr. King became famous.” Jones comes down hard on the fact that Baker “was the ONLY woman to speak” at the March on Washington, the all-caps emphasizing Baker’s gender in contrast to her race, as though those parts of her identity are separable and distinct from each other. It’s an odd choice to honor MLK by making him a second-place finisher in someone else’s story. Josephine Baker’s presence at the March, a historical accuracy, thus becomes a moment where Jones downplays King’s world-changing speech and boosts her novel’s online profile—a novel whose profits go to a white author, and a publisher who is statistically likely to be staffed with white people. (The audiobook’s narrator Adenrele Ojo, I will point out, is both black and a dancer, which is pretty awesome.) In the interview quoted above, Jones marvels at how much she learned about racism while researching Baker’s history and says: “I hope this book will awaken other people the way I have been awakened.”

This is very like what she said in Patheos about the readership of her first novel: “I always said my main audience is going to be Western women because I felt like Muslims already know these stories.” Historical fiction, according to Jones, bridges the gap between unawareness and knowledge. Unfortunately, that means that Jones’ version of Baker’s story will have more impact on white readers, since it’s safe to assume that black readers are already aware of racism as a powerful force in daily life. And every author always strives to speak more directly to her audience: the demographics will become a self-reinforcing bubble.

This is how black history can become white profits, even if your clear intent is to enlighten and inform.

It should go without saying but I’ll say it: Dray/Kamoie and Jones and so on are perfectly free to write whatever they feel like writing. But when they step up to publish that writing, when you ask for money in exchange for your work,we have to ask who these books are speaking to, and whose real-world voices they may be speaking over.

It’s about financial benefits, and who counts as an authority on the past and in the present—about access to platforms and silenced perspectives and, yes, a certain kind of ownership. Dray and Kamoie and Jones seem to feel enough ownership over black and brown art and experiences that they can leverage this material—or whitewash and whitesplain it—in a social and commercial network. For profit and acclaim.

I write this because black history is more than slavery and Civil Rights. Black history is also the devaluation—the underfinancing—of black voices in present-day commercial publishing.

Dray and Kamoie’s next project is a French Revolution-set novel with three, possibly four other white authors. The promo materials use the language of feminism to unabashedly trumpet women’s political agency and empowerment across classes—but at the time of the Revolution France was still a slave-owning empire, making race incredibly germane to any discussion of liberté, egalité, fraternité. This is also the time period covered by Dray/Kamoie’s America’s First Daughter, which deals extensively with the Jeffersons’ and Hemings’ lives in Revolutionary Paris.

This is what any working author recognizes as the building of a brand. Historical novels set around the same time, with similar covers, promoted as a bundle. Readers who like one will probably like the others—and just like that, you’ve got a backlist, and a readership, and a platform.

What you don’t see, unless you’ve been around and listening for a while, are the absences: the black and brown authors and readers and reviewers who spoke out about that racist joke three years ago, who’ve been speaking up so often while the privileged among us move on and forget: the vital critical voices outside the promo bubble, who object to a narrow white and wealthy version of historical truth.

Authors are discouraged from engaging with negative reviews, for obvious reasons—but often the practical result is that authors stop engaging with all criticism, so as a white author’s career profile grows she signal-boosts only those authors who don’t call her out on racist biases, erasure, or stereotypes. Despite the controversy, Sherry Jones’ first novel makes her a good colleague to cross-promote, because she too understands the pain of having her work criticized by the people she was writing about, and will give you the benefit of the doubt for your good intentions. That’s sisterhood.

This kind of comfort is a privilege you only get to enjoy if you don’t have to constantly shout down lies about you and people like you.

The reason I’m writing this, the reason I chased down all these forgotten scandals, is because of the way in which I learned about Stephanie Dray’s new book: I was having coffee with my editor and asked her what she had coming down the pipeline. And it was this.

Romance is big—but publishing is small, turnover is high, and institutional memory threadbare. If I hadn’t happened to remember Dray’s name, I wouldn’t have known about her problematic history. Same with Sherry Jones—I had in fact forgotten her name, but not her earlier book’s publication, and it made me much warier of her new book than I would have been otherwise. Once someone has made you one sandwich with expired mayonnaise, you hesitate the next time they offer to pack you a picnic lunch.

Historical accuracy is a mutable value. A lot of the same people who care very much whether or not your 12th-century characters can eat potatoes will tell you it’s uncouth to dredge up a joke someone made about a dead black rape victim three whole years ago. Romance gets enough bad press from outsiders, especially during February. We have to protect one another by only speaking positively about the industry. Otherwise you risk briefly slowing down a white woman’s career.

As I write this, a venture-capital-funded romance website thoughtlessly published and then hastily pulled down a piece where white romance author Laurelin Paige said real-life predator R. Kelly was exactly the kind of romance hero she would write and read and fantasize about, because she is a self-described strong woman and a feminist. Just days before that, two reactionary letters were published unedited in RWA’s Romance Writer Report: one letter cried censorship because another author had told her Confederate heroes were on the wrong side of history; the other letter called for more attention to diversity of white experiences, because Catholics and Protestants are different, and stated without citation that queer people were historically miserable until the 21st century. Last year Harlequin closed Kimani Romance—their one line where buying a book guaranteed royalty money went to an author of color. And there was the closure of Crimson Romance, notable for being the most inclusive major imprint, and the revelations of racism and harassment at Riptide…

Any one of these alone would be bad enough—but to see them come so fast, to look back over the last ten years and see so many more of them that we are all encouraged not to remember once the right apologies have been issued to the right people—and then to have an ongoing genre debate revolve around historical accuracy as though that is an unquestionably neutral concept and we weren’t swimming in a constant sea of self-inflicted amnesia…well, it leaves me with questions. Such as:

Why do we obsess over details of dress and travel and titles, and leave out whole swathes of the historical population? Whose history, whose facts, whose interpretations do we keep putting at the center and holding up as worth studying? We are defined by what we remember—but we are also defined by what we choose to forget.

These patterns are also part of black history. We should remember them accurately, too.

Recent Romances:

An Unconditional Freedom by Alyssa Cole (Kensington Books: historical m/f):

The Loyal League series has always burned with a fierce and righteous fury, but this book is an absolute conflagration. Hero Daniel Cumberland was born free but kidnapped into slavery and only rescued years later; he is a battered, bristling, murderous ball of hard-earned rage and trauma at the start of the book. We’ve caught glimpses of Daniel in the other books of the series: he was Elle’s childhood friend and would-be fiancé in An Extraordinary Union, and he had a brief but arresting cameo in A Hope Divided that hinted his past held awful and disturbing things. He stands on the cover of this book holding a lamp and a scroll, like the icon of some avenging saint. (I actually looked up the iconography to see if there was a saint reference I was missing.) Seeing the world through his eyes yanked the breath from my lungs and made me ache for his pain. What kind of heroine, I wondered, will he be matched with? Someone who can meet him in the middle of his anguish, matching pain for pain? Or someone who brings light into the storm?

Holy shit, she’s a Confederate spy.

They tell you that in the blurb so it’s not at all a spoiler, but I was too eager to read the book to glance at the blurb, and what a rush, my god. Janeta is black and Cuban; she is guarded and clever and observant and knows exactly how far her father’s wealth has protected her, and how many times it has failed. She’s not a believer in the Confederate cause—but she was steeped in its myths, and she needs to bring down the League to save her father. And now the League has paired her with Daniel. At this point in the story we know—we know, because this is Alyssa Cole’s book we’re reading—she is going to have all her sentimental illusions about her family and her slaveholder father torn away. We’ve seen Daniel’s past agony; Janeta’s greatest suffering is all still to come.

What follows is one of the most tense, brilliant, urgent, and goddamn gorgeous romances I have ever had the pleasure of reading. I don’t know how Alyssa Cole keeps doing this. I stand here in absolute awe, utterly vanquished.

He looked around as if each shadow thrown by the half-bare trees might hide some threat, and Janeta’s heart squeezed painfully in her chest. He was looking in all the wrong places; the actual danger stood just a foot away from him, offering him a drink and wishing this damned war had never drawn either of them into its gears.

Private Eye by Katrina Jackson (self-published: contemporary m/pan f):

Spy stories often have a veneer of cold misogyny about them: from the casual lady-murder of James Bond, to the tragic fringing of women in Le Carré, to the squicky sexual power dynamics of True Lies, the genre often runs roughshod over femmes and feelings in service of The Mission, or The State, or Stopping Terrorism, or whatever. If women do have agency, they often only use it to betray, and therefore retroactively justify all the suspicion and emotional distance the male leads carry around like so many chips on their shoulders. And it goes without saying that all the best spies and major diplomatic players are white. Black and brown folks get to be villains, sidekicks, and cannon fodder, and not much else.

Katrina Jackson has seen those spy stories and is having none of that nonsense here.

I’m picking up this series at the second volume, caught by the promise of a sex worker heroine written by someone not interested in shaming her for it. I got all the sweet feelings and exuberant filth I’ve come to expect from the author’s books—plus a whole agency full of hot, kinky, queer and queer-friendly spies who explicitly reject the concept of the ideal espionage agent as someone friendless, untouchable, and iceberg-pure. Maya is a fat black cam model, exceptional at her job, whose life is turned upside-down when she learns her favorite subscriber is actually a spy. Kenny first checked Maya out to get her roommate a security clearance—Kierra’s exploits as a personal assistant/girlfriend to the head of the spy agency and her husband is the plot of book one in the series—but kept coming back, entranced by her gorgeous curves and the way she laughs when she comes. At times you have to wonder how they get any spying done with all the flirting and fucking and feelings—but it’s not any less plausible than James Bond, so best to just kick back and enjoy the ride. Pun very much intended.

This was all fun and games and flirting and blowjobs until it wasn’t.

The Apprentice Sorceress by E. D. Walker (self-published: trans m/f):

I’ve always been a sucker for books in the Youths Develop Magic And Feelings genre: Mercedes Lackey, Anne McCaffrey, Diana Wynne Jones, Diane Duane, Patricia C. Wrede, etc. This story of a high-born refugee sorceress coming into her powers, and a lovelorn trans squire helping her learn how to channel them, plucks a new set of strings in that familiar key.

It’s always fun to watch an author develop a magical system—sometimes you want something with clear rules, sometimes it’s more fun if magic is organic and artistic and a little bit, well, magical. Walker’s magic leans more toward the latter, but the descriptions of it are concrete enough that it never feels hand-wavey or too plot-convenient. We can never have enough well-crafted magical hangovers, in my opinion—and while the source of magic is never really explained, each time Violette manages a spell she builds on what we’ve seen her learn, so it feels as though we’re learning along with her. A nice trick, that.

And Ned. Oh, Ned—you charming, funny, earnest, tender-hearted young man. I can see why prickly, wary Violette likes you so much in spite of herself. Our main romance is contrasted with a romance between the two royals our hero/heroine serve: we watch how many sacrifices Ned and Violette have to make, how many risks they run, until it feels like Aliénor and Thomas’ love can only come at the expense of everyone else’s safety and happiness. It’s a clever way to add tension, and it definitely means I’ll be looking out for more books by this author in years to come.

Next moment, he had turned that grin on Violette, and the breath caught in her chest. He wasn’t handsome, not by any stretch. And yet the sparkle of his eyes and the wry twist of his mouth were enough to set her heart to racing. Most inconvenient.

Polaris Rising by Jessie Mihalik (Harper Voyager: m/f sci-fi):

Time to talk about the forced proximity trope in romances! My favorite examples usually sport equal-opportunity constraint, rather than putting only the heroine at a disadvantage. Two characters handcuffed together is almost always more fun than simply chaining one character to the wall. For instance: when the runaway space princess is captured by mercenaries and forced to share a cell with a terrifying, infamous, and muscular assassin.

Together, they manage to break out of the mercenary ship—and then it’s a headlong rush from one planet to another ahead of mercs, space princes, and family spies in this action-heavy space adventure.

Heroine Ada is marvelously engaging: scrappy and fallible, with a principled emotional center that makes her feel more complex than many a not-like-other-girls-with-their-frills-and-feelings Strong Female Character [Beaton link]. The success of a first-person POV depends so much on the character’s voice: this one is snappy without overdoing the snark, and has some rich and fascinating depths of tenderness lurking beneath the blaster fire. Ada makes rash decisions as a matter of course to protect her friends and family, and is charmingly taken aback when those friends and family are outraged at the dumbass risks she took with her own life. “What was I supposed to do, leave you?” she asks, and every other character shouts “YES!” in all-caps exasperation. Several side couples are obvious sequelbait, but who’s complaining when there’s this much fun to be had? The plot hits many of the same notes as Firefly, minus the Whedonian asshattery. Or if Jupiter Ascending were not quite so bonkersville.

Our hero Marcus Loch is more of a cipher, all growly possessiveness and tragic backstory. There was a sense of loneliness and self-deprecation about him that matched Ada’s own, and I would have liked to have seen this emotional arc deepened and dwelt on a bit more. Also a certain couple of space princes definitely needed more punching in the face. Hopefully the second book (fall 2019!) will give us a bit more of this, while keeping all the fun and the fireworks.

There are moments in your life when you absolutely know what you should do and then you absolutely choose to do something else entirely. This was one of those moments.

This Month’s Isn’t That Decade Too Recent For a Historical? Historical:

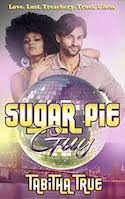

Sugar Pie Guy by Tabitha True (self-published: historical m/f):

Disco is the like bodice-ripper of music genres—in fact, they emerged at roughly the same time in the sexual revolution, as did feminist sex-toy shops. Taken together, these three different cultural products all look like rebellious antidotes to the 1970s’ particular flavor of serious, self-contained, rough-edged masculinity. Disco in particular was visibly black, femme, and queer, which goes a long way toward explaining the vitriolic backlash it received, and still receives.

So a romance set in the disco era is a natural fit, especially if you like your historicals to occasionally visit times other than the 19th century (and we know by now that I do!). Between the punchy voice and the vintage atmosphere, this book has a lot going on. It’s a classic small business-versus-rich-developer setup, with a welcome emphasis on what being a community means. Heroine Bobbie is delightful and ambitious, hero Randy (heh) is more earnest and tender than many others of his archetype. (The moment he’s abashed to realize the hot stewardess who’s hitting on him doesn’t remember she’s hit on him before is a neat twist on an old hero-POV chestnut.)

Every Lesser Rule of Romance has an exception, and this one is: do not name actual bands and songs unless you are writing a historical and using older songs for period detail. The playlist I built while reading this is unbelieveable. It was fascinating to see different dance moves embodied in print; most of the dance books I’ve read have leaned strongly toward ballroom and ballet. This book’s disco scenes made me want to get up and move. And sing. And buy something with sequins on it.

He made his way to the VIP banquette, and greeted Miss Foster, her hip stylist, and a sweater-wearing man who seemed to have wandered in from a book club meeting. Chit-chatting with them was nice, but when the intro to “Never Gonna Leave You” came booming out of those speakers, he cut it short as graciously as he could. He was going to have that dance, with that girl, if it was the last thing he ever did.