Thursday Comics Hangover: Spider-Man grows up?

One of my favorite aspects of comics is the way they leave time largely up to the reader. A good artist can coax a reader into reading at a certain speed or rhythm through manipulation of panel layouts and spatial tricks on the page, but ultimately, every reader engages with a comic at their own pace. There's no real way to watch a movie at your own pace, but in comics the passage of time is a collaboration between creator and reader.

It's odd, then, that superhero comics always feel so timeless. Many of the characters fans have been following since the 1940s have basically become immortal — ageless beings who wear and discard the trappings of contemporary culture as easily as you or I might swap a pair of pants. When it comes to Superman and Spider-Man, we have no control over the passage of time. They stay roughly the same age forever, and we pass them by on our way to the grave.

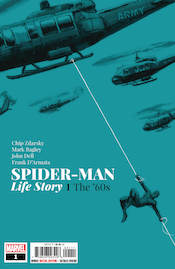

Yesterday, the first issue of a new series by writer Chip Zdarsky (who you may also know as the artist of Sex Criminals) lifts the spell of immortality off of one of the most popular characters in comics. Spider-Man: Life Story is a limited series that begins with Spider-Man's origin in 1962, and then it follows the character in "real time" as he ages to the present day. Each book in the series is set in a decade in the character's life, beginning with the 1960s.

This idea has been done before: John Byrne wrote and drew a series called Generations at DC that followed Superman and Batman through the years, allowing the characters to age and have children and pass their legacies on to future generations. But it's just too good a concept to only do once, and Zdarsky's interpretation of the idea is much less gimmicky than Byrne's, which contorted itself into a sort of rhyming structure for no good reason.

The first issue of Life Story allows Zdarsky to use the Spider-Man character to examine the Vietnam War. Though early Marvel Comics are praised for being politically active in a way that DC Comics at the time were not, Marvel's creators largely left the war out of their books. Perhaps including Vietnam in comics would have felt too frivolous. But in retrospect, it's bizarre that Peter Parker never really expressed much angst about the draft.

In Life Story, Zdarsky finally puts Spider-Man through the moral conflict that the character always avoided. He wonders aloud, "What do I do? I have power. Shouldn't I be--shouldn't I have a responsibility to go [to Vietnam]?" Every young person in the late 1960s had to ask themselves some variation of that question, and it only makes sense that Peter Parker, with his guilt and his dutiful nature, would ask those questions.

Life Story is drawn by Mark Bagley, who has become the quintessential Spider-Man artist for at least two generations of comics readers. His work has never had the bizarre edge of Steve Ditko, but in Life Story he captures the wholesomeness of John Romita, and it works perfectly. The book might lack some of its heft if it were drawn, say, by some quirky indie comics superstar. Bagley has spent so many years as a straightforward superhero artist that the moral dilemma of Vietnam feels even more complex when his characters question it.

I don't want to spoil the last page of Life Story, but let me say that it's one of the most surprising final pages I've read in a superhero comics in recent memory. It's a decision that actually feels brave, and it left me panting to read the next issue. This could be the most interesting Spider-Man book Marvel Comics has published in years — possibly since the wildly unpleasant issue in which Seattle cartoonist Peter Bagge imbued Peter Parker with Ditko's Objectivism. This is only the first of six issues, of course, and pretty much anything could happen in the rest of Life Story. But after this first issue, I'm hooked.