Thursday Comics Hangover: Another day in paradise

For as much as incel-driven conservative comics groups love to whine about "social justice warrior" movements in comics, the truth is that comics are currently in a relatively apolitical period. Of course superhero comics are full of cheerleading for inclusion, and you can find a ton of easy Trump parodies in all the usual places. But aside from a few smart books like Black and Young Terrorists (both of which were originally published by Black Mask Studios, for whatever that's worth) you don't see many contemporary comics taking on uncomfortable political discussions.

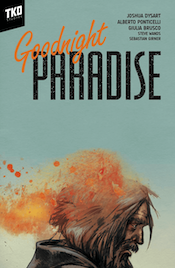

Goodnight Paradise is a deeply political book. It resembles the world I see out my window, and it takes in the whole panorama — from the modern tech-powered American boom economy to the homeless encampments popping up in plain view of all that wealth.

The description of Goodnight Paradise sounds like pretty much any sunbaked noir: a young woman is killed and one man, an outsider named Eddie, investigates the mysterious circumstances of her death. The trail leads him to the seat of power in his city. But the particulars of this noir are unlike any I've seen before: Eddie is a homeless man struggling with mental disorders and addiction, and his city is Venice Beach, California, which is the home base of Snapchat.

Thanks to a tight, clever script by Joshua Dysart, Goodnight Paradise hums along while giving us enough atmosphere to appreciate the dynamics of Venice Beach: the homeless people sit on benches and in run-down RVs, sneering at the young and affluent Snap employees wandering past with their hired security forces. The beach itself is a kind of no man's land where everyone gathers, but every situation is fraught with class distinctions and seething hatred.

Alberto Ponticelli is the perfect artist for a hard-boiled detective comic: he understands the importance of characters who look the same on the 5th page of the fifth issue as they did on the third page of the first issue. Their world has to be rock-solid, and readers have to be able to understand where everyone and everything is in relation to everything else. Without a solid sense of worldbuilding and character consistency, the mystery would feel airy and insubstantial. Ponticelli keeps everything grounded and makes us care deeply for Eddie as a character.

Colorist Giulia Brusco contributes more than just a beach-y spray of color to the book: part of the backdrop of Venice Beach is the smoke and smoggy orange-smeared sky caused by nearby forest fires. The fires get earlier every year, and they contribute to Eddie's claustrophobia. When his mania gets out of hand he sees fires everywhere: on people's heads, on buildings, in palm trees. The whole world is burning.

Though Goodnight Paradise is set in California, it could almost as easily be set in the Seattle of 2019, where tech overlords try not to stare directly into the eyes of homeless people and where the skies turn orange and belch smoke every summer. We Seattleites intimately know the rhythms of income inequality and of climate insecurity that drive the waltz of Goodnight Paradise. It is a deeply political comic — one that represents the year 2019 with such accuracy and power that it's sometimes hard to stare for too long. Mirrors are like that, sometimes.