John Englehardt's debut novel breaks two of the biggest rules of writing class, and he's cool with that

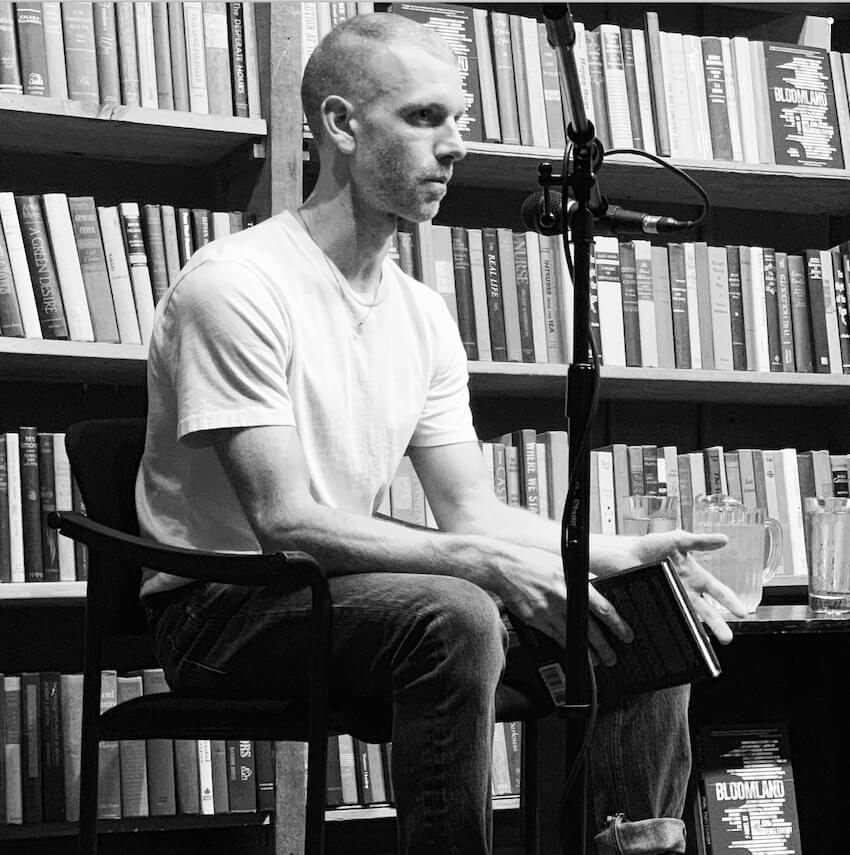

When I joined Seattle writer John Englehardt onstage at Elliott Bay Book Company last month for a well-attended book launch party for his first novel Bloomland, the very first question I asked him was “what’s your author origin story — were you bitten by a radioactive Faulkner?”

Set in Arkansas, Bloomland feels through and through like a novel in the southern tradition. Its cadence, its understanding of human nature — by which I mean it has a keen eye for how we behave both alone and in groups — and its complicated relationship with poverty and religion all resonate like a book by a southern author.

Englehardt admitted that Faulkner was a heavy influence on Bloomland. “When writing this book, I did go back to Absalom, Absalom! in particular. I love that book.” He especially found inspiration in the way that Absalom unfolds — “a kind of peeling back the onion.” That structure helped him figure out how to tell the story: “I really wanted to have almost everything up-front [in Bloomland]. Specifically, I didn't want to write a thriller or sensationalize the topic.”

About that topic: Bloomland is the story of what happens after a school shooting at an Arkansas university. When you take the sensitive subject matter into account and also consider the fact that It’s written in the second person, the book violates pretty much every writing-class warning in the instructor handbook. Those are two big danger zones for any writer, let alone a first-time novelist.

“I tried to write the novel a different way,” Englehardt admitted. “I tried to write it in first person. I tried to write it in third person. And it ended up not working out. It felt disingenuous.”

For Englehardt, the second person and the subject matter went hand-in-hand: “one of the biggest things I was trying to think about when writing this book was the issue of shared responsibility. So I became really drawn to the second person for the way it interrogates the reader.” By addressing the reader directly, he believed Bloomland could more clearly address “how our individual actions can be seen as complicit in a proliferation of mass shootings and ceremonial violence.”

And that’s where the southern regionalism came in. “There was something about the way I felt this particular story needed to be told that really required the richness and texture and layer consciousness and attention to the landscape of the south,” Englehardt said. He grew up in Washington state, went to school for four years in Arkansas, and it wasn’t until 2014, when he was finally back in Seattle, that he started to write about Arkansas. “When I was in Arkansas, I didn't write about Arkansas at all,” he said. “But I took notes. I had notebooks filled with Arkansas stuff.”

This week, a movie is being released by a major Hollywood studio that has been at the center of a conversation about art and responsibility. The director and star of Joker didn’t seem to stop and think about the ways that their work might be interpreted and celebrated by the alienated young men who are most prone to dramatic violent outbursts in America today. Did Englehardt feel a responsibility in writing about a school shooting?

“It's one thing I've thought about all throughout writing the novel,” he said. “And initially I didn't think I was going to write about the shooter. But then as I did more research and was thinking about the issue of shared responsibility, I realized that there are so many kinds of myths out there about what makes a mass shooter and about the social roots of mass shootings that we keep repeating every time one of these things happen.”

Englehardt listed those causes in a rote voice, the way we hear them listed on the evening news: “that they did this specifically because they had a mental illness, or because they were bullied, or because they were addicted to buying video games. I started to think it would be instructive and necessary to write from his perspective as a way to write against those myths — by not making him those things.”

One book that helped Englehardt the most in the writing of Bloomland was Sister Helen Prejean’s memoir of her time counseling a death row inmate, Dead Man Walking. “One of the biggest things she struggles with is the extent to which we are taught that to extend understanding and especially compassion towards someone who's done something unthinkable like murder is to betray the victims and to condone what they did,” he said.

In her book, Prejean suggests that we “can have understanding and compassion and treat someone like a human while also at the same time not condone what they did — not be their apologists, and not strike back at them, or elevate them. Sometimes when we declare someone as evil and declare them as a monster, it's a way of distancing ourselves from them.”

In the end, Englehardt concluded, distance is the worst thing you can do. “You know, this is the person that our community created.”