Thursday Comics Hangover: Can you teach a new dog old tricks?

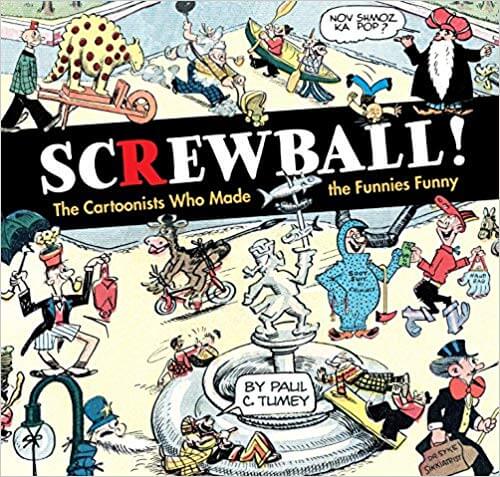

Tomorrow night at Elliott Bay Book Company, I'll be interviewing Seattle author Paul C. Tumey about his massive new art book, Screwball! The Cartoonists Who Made the Funnies Funny. It's a huge collection of brief essays of cartoonists from the beginning of the 20th century, when the modern comic strip was just getting started as an art from, along with over 600 cartoons and illustrations — many never before reprinted.

Even if you're not a comics nut, you've likely heard the names or know the work of three of the cartoonists highlighted in Screwball!: Rube Goldberg, whose name literally became the name of his elaborate machines devised to perform very simple tasks; Krazy Kat creator George Herriman; and EC Segar, the cartoonist who came up with Popeye. Tumey smartly focuses on the lesser-known work of these cartoonists, rather than going over the greatest hits that have been covered again and again.

Segar, for instance, drew a series of strips about commuting in Chicago. One of them, "Looping the Loop" was an observational strip about life in the big city in 1919: bizarre clothing trends, interesting noses on pedestrians, a series of comparisons between classic sculptures like The Thinker and Segar's gawky characters striking the same poses. You can draw a straight line from these gag strips to MAD Magazine.

But the total unknowns, the cartoonists who elevated the medium to an art form and then disappeared, are perhaps most interesting. Consider Clare Dwiggins, a cartoonist known as "Dwig" who devised one strip as a sequel to a classic of American literature. As Tumey writes:

In the early 1940s Dwig returned to his "old-fashioned Tawin stories with *Huckleberry Finn*, a new daily strip for the Philadelphia Ledger Syndicate. The stories offer wacky adventures, such as a 1940 continuity in which the boys travel the Mississippi River not on a raft, but inside a giant robot duck. Also in these years, Dwig penned a series of gentle, silly Tom and Huck comic book stories for Street and Smith. These are tucked, like a flower in a machine, inside heroic titles such as *Doc Savage Comics*.

It's true that these old strips require a kind of learning curve. They read as more than a little stilted in modern times — partly a consequence of outdated language and partly a difference in the way comics portrayed time and action over a hundred years. But Tumey is a great and observational guide who will hold your hand and contextualize each of the works. He also, presumably, selected some of the most accessible work from this bygone era for modern audiences to enjoy.

Comics have always been a disposable art form. They were thrown out with the newspaper, and children read them and re-read them until they fell apart. With Screwball!, Tumey is snatching these treasures from the scrap heap and presenting them to audiences a century or so later. Comics have moved on, it's true — there's more variety in the figures' sizes in the panels, the balloons aren't quite as packed full of words, and artists feel empowered to play with perspective and pacing in ways that were unimaginable back in the day.

But maybe today's cartoonists can learn something from these strips, too. For one thing, the level of detail in each panel — the sheer amount of story and art crammed into each square inch — is much denser than most of today's comics. And for another, the slapstick comedy in these strips is much broader, much more physical, than most of the comedy you'll find in comics today. Tumey is excavating more than just a nostalgia trip: he's pointing to a lost form of communication — one that can inform a whole new generation of artists.