The secret of classic comics, according to Paul Tumey: "Things fall apart."

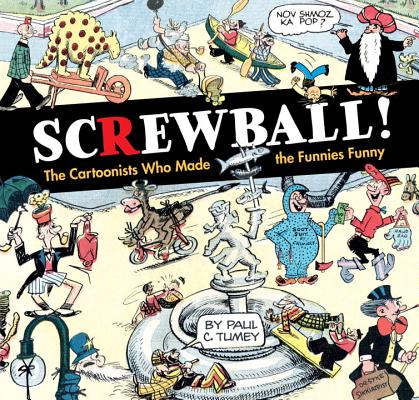

I interviewed Seattle author Paul C. Tumey last month about his book Screwball! The Cartoonists Who Made the Funnies Funny at Elliott Bay Book Company. The book is an anthology of some of the earliest pioneers of comics art from the funny pages, and Tumey is a fantastic guide: he can explain the nuances of comics as well as just about anyone, and his passion for the classics of the funny pages is infectious.

Pretty much every film buff knows that the early years of cinema is a wasteland of lost art, as very few of the first silent films were archived. When I told Tumey that I feared the same was true of comics, he had some good news: in the middle of the 20th century, America's public libraries were eliminating their archives of old newspapers, but "before they did, they photographed them for microfilm," Tumey explained.

Granted, the switch to black-and-white microfilm means that the vibrant colors of many old Sunday comic strips have been lost forever, but Tumey is grateful that most of it exists at all. "It's amazing that this stuff's still accessible," he says. "It's only about a hundred, 120 years old. That's not too long in the span of things, but in America, that's forever."

But to make Screwball!, Tumey couldn't just rely on digital archives of old newspapers. "In addition to the five years of research [on the book,] I also spent five years looking at eBay," he laughs. Tumey would bid on classics of the form, and he'd frequently get outbid by one of the handful of comic strip collectors out in the world. For those strips that he couldn't dig up through internet bidding, Tumey says the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library at Ohio State University is "a tremendous, resource for books like this and for comics scholars." After he gets his hands on the strips in the best condition he can find, Tumey says Photoshop ensures that he can "clean this stuff up so it doesn't look too bad."

One aspect of these early cartoons that has been lost to time is the actual process of cartooning. I asked Tumey about the density of the jokes on these giant pages — one large Sunday page could have four dozen visual gags going on in the background. Were they all drawn out in elaborate detail, or were the artists winging it as they went along?

"I do have an original by Clare Victor Dwiggins, who was notorious for crowding background details," Tumey says. "You can see that the main figures are penciled. However, he may have just drawn the background gags in with an ink pen."

Part of the vibrance of the early cartoons comes from their immediacy. "They had to create one of these a day," Tumey says. "The dailies were just a few panels, but the Sundays were big. This was a lot of work, and some of them were doing two and three strips at the same time. So, I don't think they spent a lot of time on them—it's very spontaneous."

It's important to note that Tumey didn't collect Screwball! to archive the past. He wanted to create guideposts for the future. Tumey has been a part of Seattle's comics community for decades, and he thinks these classic cartoons are "a vital art form and a part of our lineage." Tumey wanted to put the book together so "modern cartoonists could look at it and go, 'hey, this is kind of similar to stuff that I do or stuff some other cartoonist does.'"

"For me this stuff is as fresh as a comic that was created last week," Tumey says. "So I wrote about it from that perspective and I deliberately avoided a stuffy academic tone."

But this isn't just a reference for cartoonists. Tumey thinks that we could all use a little screwball in our lives. "Most humor these days has an undertone of irony and cynicism," he says. "One of the things I love about the humor in these comics is it's not ironic, it's just silly for being silly's sake. The undercurrent of screwball comics is a sense that the world is absurd, that things will fall apart. These comics are tributes to the second law of thermodynamics, which is that things fall apart eventually." So if everything's falling to chaos and ruination, you might as well have a good laugh about it.