Thursday Comics Hangover: Internal affairs

Before I read Kevin Huizenga's comics, I thought that the fiction of interiority was best left for literary fiction. I'd never seen a comic that could convincingly get me inside a character's head the way a good literary monologue could. When you're looking at a comic, after all, you're almost by definition outside the action, outside the characters. You're on the outside looking in.

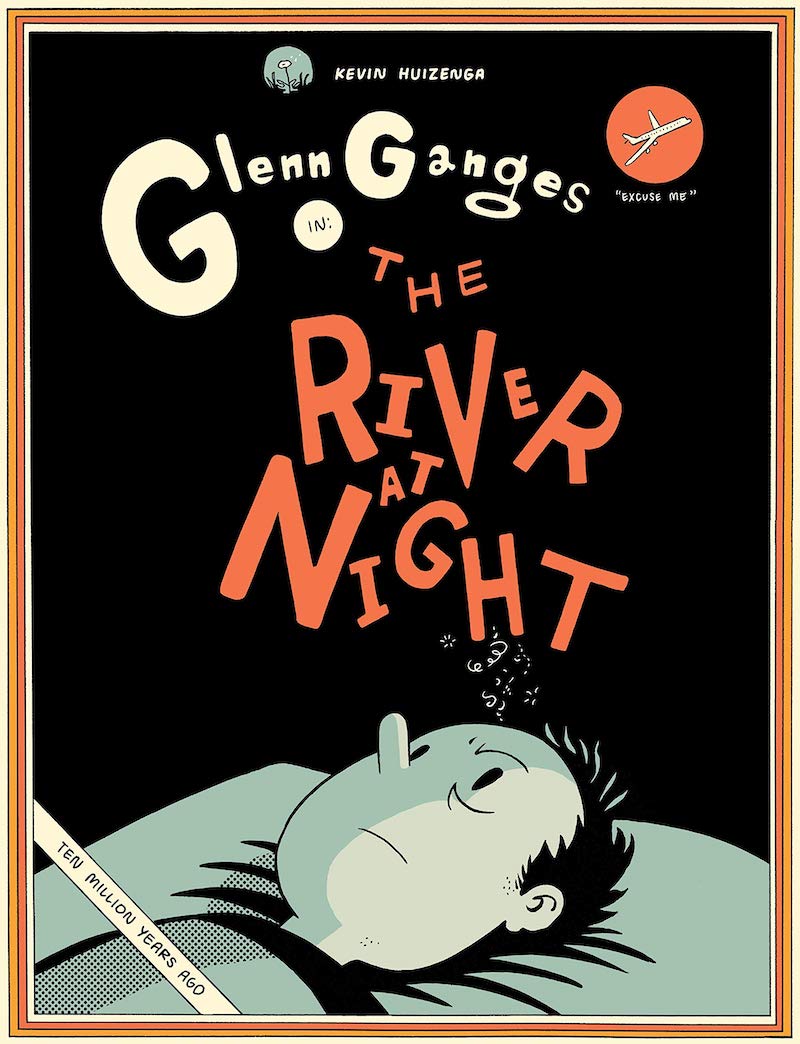

But Huizenga's comics collected in The River at Night taught me that comics can just as ably take a reader inside the head of a protagonist and show you what they're thinking. In retrospect, it's obvious. Why would prose be particularly great at simulating thoughts when our thoughts are a blend of words and pictures — the very definition of comics?

The River at Night is a collection of comics about a normal middle-aged married man named Glenn Ganges. One day, Glenn drinks too much coffee too late in the day. As a consequence, he can't sleep. He tosses and turns at night, captivated and kept awake up by his restless mind. He recalls recent events, wonders about mortality and music, and tries to fathom the hugeness of geologic time. He barely moves in the whole book.

On the surface, Huizenga's art looks deceptively simple, like Popeye cartoon. But when Glenn's mind begins to wander, Huizenga's knack for illustrating complicated ideas in as few lines as possible becomes clear. Segments in which Glenn becomes swamped in his thoughts, or wanders around his home trying to force his eyes to become accustomed to the darkness, are illustrated in a minimalist style that lands with maximalist effect. Nothing happens in this book, but that's everything.